MIT researchers observe hydrogen’s effects on metal to design safer storage tanks

Hydrogen, the second-tiniest of all atoms, can penetrate right into the crystal structure of a solid metal. That’s good news for efforts to store the fuel safely within the metal itself, but it’s bad news for structures such as the pressure vessels in nuclear plants, where hydrogen uptake eventually makes the vessel’s metal walls more brittle, which can lead to failure. But this embrittlement process is difficult to observe because hydrogen atoms diffuse very fast, even inside the solid metal.

Now, researchers at MIT have figured out a way around that problem, creating a new technique that allows the observation of a metal surface during hydrogen penetration. Their findings are described in a paper appearing today in the International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, by MIT postdoc Jinwoo Kim and Thomas B. King Assistant Professor of Metallurgy C. Cem Tasan.

Hydrogen fuel is considered a potentially major tool for limiting global climate change because it is a high-energy fuel that could eventually be used in cars and planes. However, expensive and heavy high-pressure tanks are needed to contain it. Storing the fuel in the crystal lattice of the metal itself could be cheaper, lighter, and safer — but first the process of how hydrogen enters and leaves the metal must be better understood.

“Hydrogen can diffuse at relatively high rates in the metal, because it’s so small,” Tasan says. “If you take a metal and put it in a hydrogen-rich environment, it will uptake the hydrogen, and this causes hydrogen embrittlement,” he says. That’s because the hydrogen atoms tend to segregate in certain parts of the metal crystal lattice, weakening its chemical bonds.

The new way of observing the embrittlement process as it happens may help to reveal how the embrittlement gets triggered, and it may suggest ways of slowing the process — or of avoiding it by designing alloys that are less vulnerable to embrittlement.

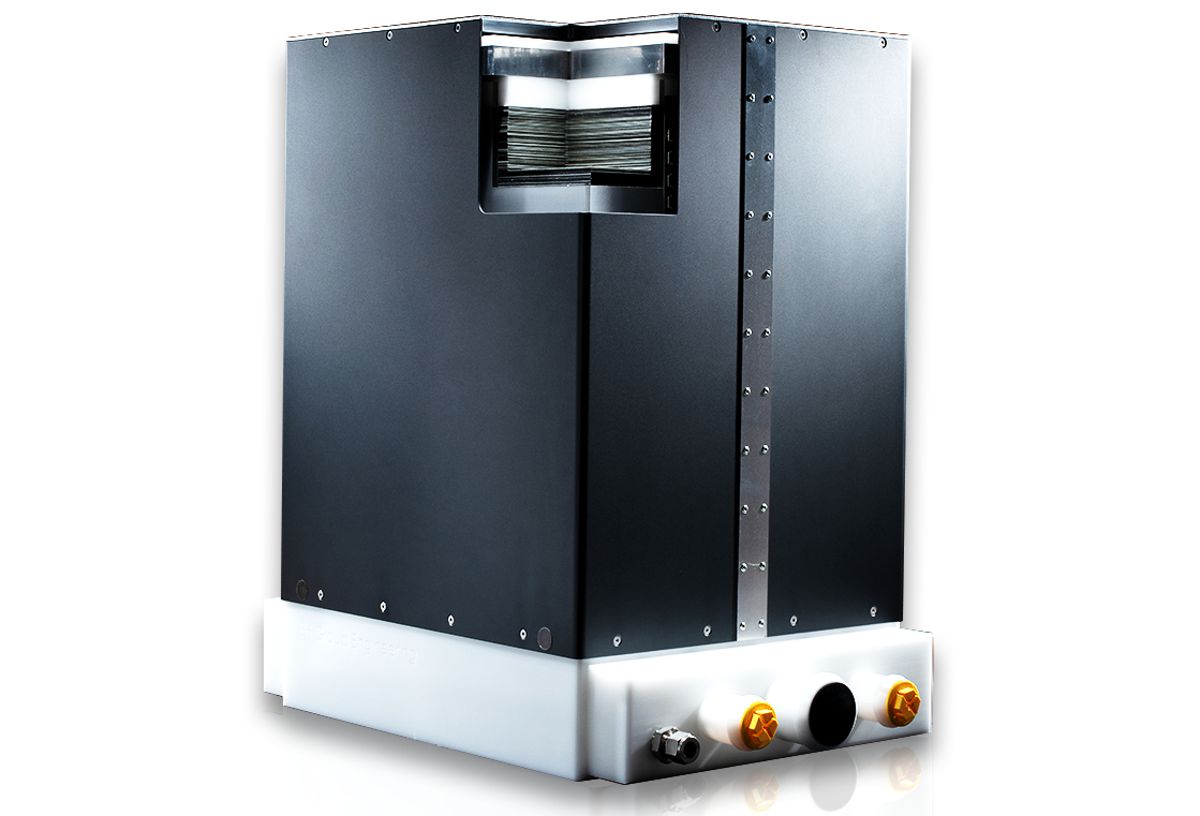

The key to the new monitoring process was devising a way of exposing metal surfaces to a hydrogen environment while inside the vacuum chamber of a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Because the SEM requires a vacuum for its operation, hydrogen gas cannot be charged into the metal inside the instrument, and if precharged, the gas diffuses out quickly. Instead, the researchers used a liquid electrolyte that could be contained in a well-sealed chamber, where it is exposed to the underside of a thin sheet of metal. The top of the metal is exposed to the SEM electron beam, which can then probe the structure of the metal and observe the effects of the hydrogen atoms migrating into it.

The hydrogen from the electrolyte “diffuses all the way through to the top” of the metal, where its effects can be seen, Tasan says. The basic design of this contained system could also be used in other kinds of vacuum-based instruments to detect other properties. “It’s a unique setup. As far as we know, the only one in the world that can realize something like this,” he says.

In their initial tests of three different metals — two different kinds of stainless steel and a titanium alloy — the researchers have already made some new findings. For example, they observed the formation and growth process of a nanoscale hydride phase in the most commonly used titanium alloy, at room temperature and in real time.

Devising a leakproof system was crucial to making the process work. The electrolyte needed to charge the metal with hydrogen, “is a bit dangerous for the microscope,” Tasan says. “If the sample fails and the electrolyte is released into the microscope chamber,” it could penetrate far into every nook and cranny of the device and be difficult to clean out. When the time came to carry out their first experiment in the specialized and expensive equipment, he says, “we were excited, but also really nervous. It was unlikely that failure was going to take place, but there’s always that fear.”

The work was supported by the Exelon Corp.

The image shown above is the atomic structure of Graphene.