TRL asks how many road deaths are acceptable?

In this article Dr Neale Kinnear, Head of Behavioural Science at TRL examines our acceptance of road deaths.

“In the video above from Western Australia’s (WA) Road Safety Commission, a researcher stops a man in the street and says, “Last year 161 people died on WA roads. What would be a more acceptable number?” The man pauses for a moment before uttering “Uuum. Acceptable? 70 maybe?”, then with the look of more certainty adds “Probably 70”.

“Why 70? What calculation has he done to come to that figure? He was so uncertain to begin with, but within a few seconds he has convinced himself that 70 feels about right.

“What happened here is what psychologists call the ‘anchoring heuristic’. The anchoring heuristic is a cognitive bias that affects human decision making. It simply refers to the process of relying too much on an initial value, that is adjusted to produce a final answer. Different starting points will yield different answers, even when the initial number is completely unrelated. Tversky and Khaneman famously demonstrated this by asking participants to spin a wheel numbered 0-100. Once a random number was shown on the wheel, they asked participants how many African countries were in the United Nations. Those who spun higher numbers gave higher estimates; those who spun lower numbers gave lower estimates. Despite being completely arbitrary, participants were influenced by the initial figure to inform their decision.

“Let’s try this out. In a single year, 354 people died on Great Britain’s roads in collisions involving a driver aged 17-24. What would be a more acceptable number?

“Maybe the question should be ‘is this an acceptable number?’. After all, this is down 79% since 1990, albeit to a level that has plateaued in the last 5 years. Maybe we have done enough. Or maybe we need to consider all 38,534 injured casualties from collisions involving a young driver.

“Young and novice drivers aged 17-24 make up 7% of licence holders but are involved in a quarter of the injury collisions (and 24% of fatal collisions) on Great Britain’s roads. On average, 17-24 year old drivers drive half as many miles as all drivers. This suggests that despite welcome reductions in the last 30 years, young and novice drivers remain at greater risk on our roads.

“It is not their fault. All newly licensed drivers, irrespective of their age, are at increased risk when they start driving, simply due to inexperience. In the first year of driving, a 17 year old’s risk will reduce by 6% due to maturity but 36% due to experience (assuming they drive around 4,500 miles). Despite being licensed, clearly they are still learning. During this time, they will encounter circumstances of heightened risk. For example, the risk of collision involvement for young drivers is 8 times higher between 2am and 4am, on both weekdays and weekends. Similarly, young drivers are exponentially more likely to be involved in a collision with each similar aged passenger in the car.

“On 2nd September I gave evidence to the Transport Select Committee’s inquiry into the safety of young and novice drivers. It was a privilege to play a part in providing evidence to a political process that is designed to think critically and contains cross-party members. The overwhelming outcome was the consistency of witness response in favour of a phased licensing approach to be adopted in Great Britain.

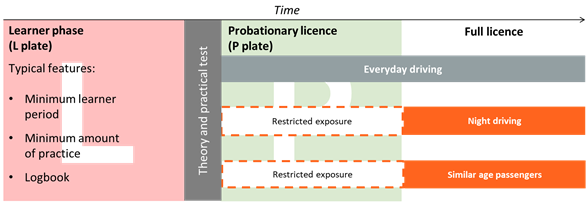

“A phased approach to licensing (often referred to as Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL)) aims to complement the natural learning process. This is achieved by encouraging driving experience in safer contexts, gradually exposing new drivers to more complex and dangerous situations over time. Simple features that could be added in Great Britain include a minimum learner period, and a probationary phase post-test that includes temporary restrictions (e.g. 6-12 months) on carrying peer-passengers and driving at night. Drivers would then graduate to a full licence.

“This approach to licensing has been adopted in every state in the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand; 73 different jurisdictions. In every case it has reduced collisions and casualties involving young and novice drivers, with reviews establishing reductions in the magnitude of 20-40%. The evidence is overwhelming. In Great Britain, phased licensing was considered in a consultation in 2002, but ultimately rejected in 2004. A TRL review in 2013 provided an overview of the evidence for this approach and further work estimated the regional impact across Great Britain.

“Were this approach adopted in 2004 and applied to only 17-19 year old drivers, it is feasible that between 2005-2018 56,775 casualties could have been prevented, including 7,833 killed or serious injured. 547 lives might have been saved. Based on DfT’s casualty prevention values, this equates to over £3.5 billion.

“The details of a phased licensing approach in Great Britain need to be designed and considered. Concerns around youth mobility, employment and enforcement need to be appeased. I may blog about this separately, but ultimately, there is no evidence of adverse effects across the countries that have already adopted this approach. If they can do it, why can’t we?

“Two parents of young people who died in road collisions also gave evidence to the committee. Their stories put faces to the numbers. Their loss has changed their lives forever. In the Western Australia video, after the man says 70, the production team bring 70 people around the corner, “this is what 70 people looks like”. Visibly emotional, he says “that’s my family”. The researcher finally asks, “So now, what do you think would be a more acceptable number?”. He responds “Zero”.