The old Car Jump Study physics problem

Many introductory physics courses present students with a theoretical scenario for an assignment. If an automobile is moving at a steady speed over a hill in the shape of a vertical circular arc, what is the maximum speed it can attain without losing contact with the road at the crest of the hill?

However, this problem is inherently flawed, “because if the speed of the car is such that it would lose contact at the crest, then it will lose contact well before that point,” according to Carl Mungan, a professor of physics at the U.S. Naval Academy.

In The Physics Teacher, by AIP Publishing, Mungan demonstrates that, despite numerous textbook references stating otherwise, a car will leave the ground on the downside of a peak.

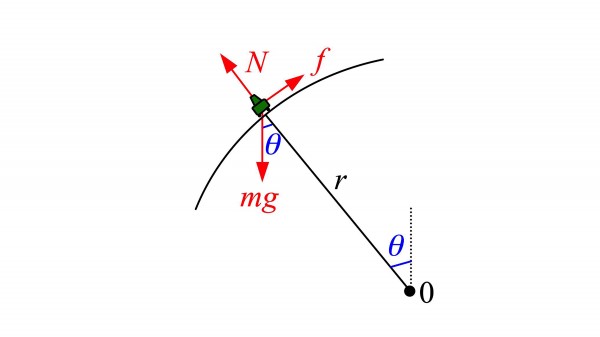

“It is usually assumed in physics textbooks that a car would lose contact at the exact crest of a hill having a circular cross section,” Mungan said. “But the normal force on the car is, in fact, smaller when the road is sloped than when its tangent vector is horizontal.

“In addition, if one’s foot is off the accelerator, or if you’re doing a demo with a matchbox car on a convex track, the car’s speed decreases as it climbs the hill. Both factors imply cars will not leave the road at the very crest.”

The study presents three separate cases to illustrate the nuances of the different physics principles at play. The first examines a rigid object sliding frictionlessly like a hockey puck on ice. The second focuses on an unpowered object rolling without slipping, such as a ball. The third features a car that is driven by applying pressure on the accelerator pedal but not so hard that the tires are slipping at their points of contact with the road.

By illustrating the dynamics in each case, Mungan ultimately presents a compelling argument, dispelling the long-held notion a car can leave the road at the top of a smooth hill.

So, how does a car perform a jump? There are a number of websites that give tips on automobile hill jumping, but most of them include strong cautions.

“For actual rally car driving, it is most likely a jump will occur just beyond the crest of the hill,” Mungan said.

The article “Over The Top” is authored by Carl Edward Mungan. The article appeared in The Physics Teacher on Nov. 19, 2021 (DOI: 10.1119/5.0051081) and it can be accessed here.