Rural Road upgrading and rehabilitation in developing countries

Construction methodologies and materials properties as results of different financial, environmental, social and quality requirements: case studies of rural-urban linkages and regional development

One of the determining factors for the economic growth of any country is the presence of a reliable transport system suited to the needs of the territory.

Considering that agriculture, food production and related sectors represent, for the rural areas of developing countries, roads represent a great opportunity for their economic growth, it is clear that the transport system in these areas must be developed to promote sustainability.

From what emerged in the context of several international infrastructure projects (in which the author took part) the criteria for design, construction and maintenance of roads in use in the most developed countries, is not directly transferable to developing countries, without changes.

Only through a deep understanding of the physical, geomorphological and geotechnical processes of specific areas and a conscious, and sometimes innovative, use of the materials and resources available, it is possible to reduce the uncertainty connected with the design risks, and accordingly, with the need to combine the different components of sustainable development – social, economic, and environmental.

The degree of achievement of the set objectives varies considerably from country to country, as it is strongly conditioned, in addition to the ‘technical’ difficulties, by the socio-cultural context and the efficiency of the local governances.

Well-engineered rural roads and their connectivity to the main network

In poorer countries, rural roads are often a lifeline for local communities. Indeed, there is a close correlation between low accessibility to basic infrastructure and to markets and poverty.

Often, due to the presence of non-engineered/unmaintained unpaved rural roads and adverse weather conditions, such roads become unusable, interrupting or limiting the accessibility to basic services at the moment of major need.

The peripheral nature of many rural areas, and accordingly, the unavailability of qualified contractors and suitable production plants (likely situation in developing countries) – as well as the access difficulties normally present in these areas, are among the main constraints affecting the development and the maintenance efficiencies of the rural road network.

In the presence of an effective transport system and roads built and maintained according to aimed and recognized standards (likely optimal situation in more developed countries) the rural road network allow a smooth and sustainable connectivity to the main road network and, therefore, greater accessibility to services, transport networks and urban areas.

However, in developing countries a large part of the road network (not just rural roads) more commonly remains like a set of dirt roads made with ‘unselected’ and native materials available along the routes, laid omitting important construction criteria (such as a proper drainage system). These roads, often inaccessible in rainy periods, present the following problems:

- poor durability due to high erosion and wear;

- lack of works of surface and subsurface drainage systems;

- damage to health and agricultural activities caused by the excessive production of dust;

- damage to road users and goods due to potholes and other irregularities in the road surface;

- excessive need for maintenance and repairs;

- environmental damage induced by the activities undertaken for the production and transport of the materials necessary for continuous maintenance needs.

As regards the unpaved roads built according to engineering criteria, and through the use of appropriately selected materials – with granulometric and physical-mechanical characteristics generally defined at specifications level – it is clear that the choice of this type of pavement shall be subordinated to the volume of expected traffic (preferably low volume) and specific environmental conditions.

In general, the solution with bitumen-bound pavement materials is preferable, as it is the one that offers the best conditions of safety, accessibility in all weather conditions, comfort and durability.

With the growth of economies and the increase of traffic volume and speed, the pavement – in order to avoid situations of general unsustainability due to excessive maintenance, presence of dust, etc., should not be made with unbonded materials.

An example of how the increase in the volume of vehicular traffic, in particular heavy traffic, has determined the need for a wider roadway, is shown in Fig 10. In this case (it is not a rural road, but one of the main arteries of the Nigerian road network) the initial situation is clearly unsustainable for the environment and the health and safety of all users.

The main environmental and social benefits following the completion of this project were:

- decrease in road accidents and greater safety resulting from reconstruction according to adequate standards;

- reduction of pollution as a beneficial consequence of more regular vehicular traffic at constant speed and reduction of dust caused by improper use of shoulders as additional lanes;

- reduction of transport times and costs thanks to the improvement of quality and efficiency of the new infrastructures;

- greater accessibility to products and services present in the major regional cities;

- creation of job opportunities within construction sites.

The completion of the project will lead to greater mobility of people and goods, thus ensuring correct accessibility by rural communities to the services and facilities available in urban areas and promoting an overall improvement of the socio-economic conditions.

Rural road design and construction

For the design and construction of rural roads we may refer to documents available in international technical literature (e.g. Structural design of flexible pavements for interurban and rural roads, DRAFT TRH4, Pretoria, South Africa, 1996 – Structural design, construction and maintenance of unpaved roads, DRAFT TRH20, Pretoria, South Africa, 1990).

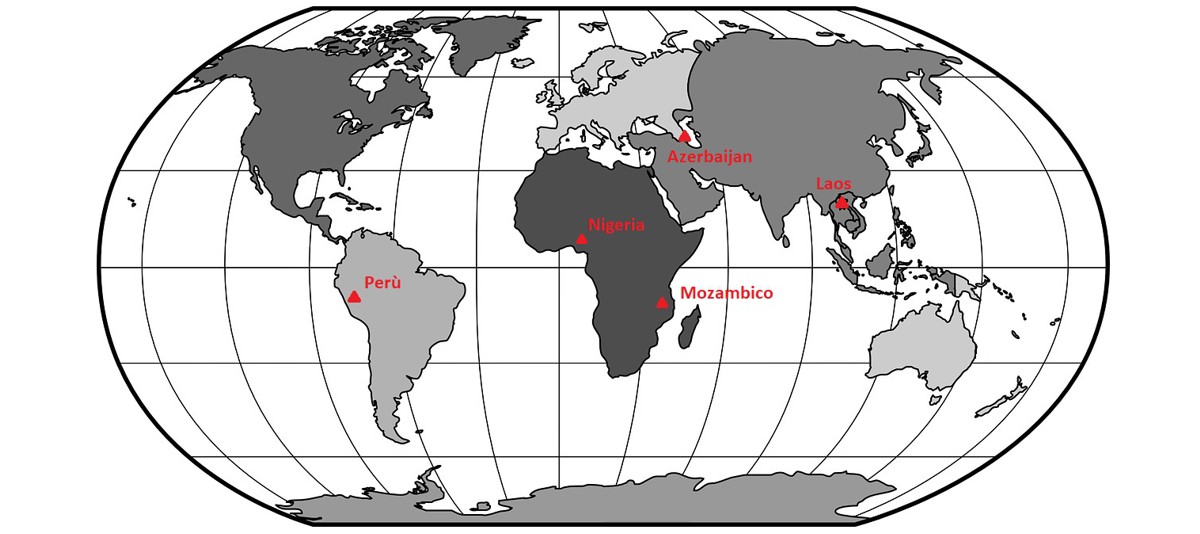

In an effort to provide some practical examples, the following typical cross sections refer to three rural roads projects in which the author was personally involved as Laboratory Manager and Materials (QA/QC) Engineer:

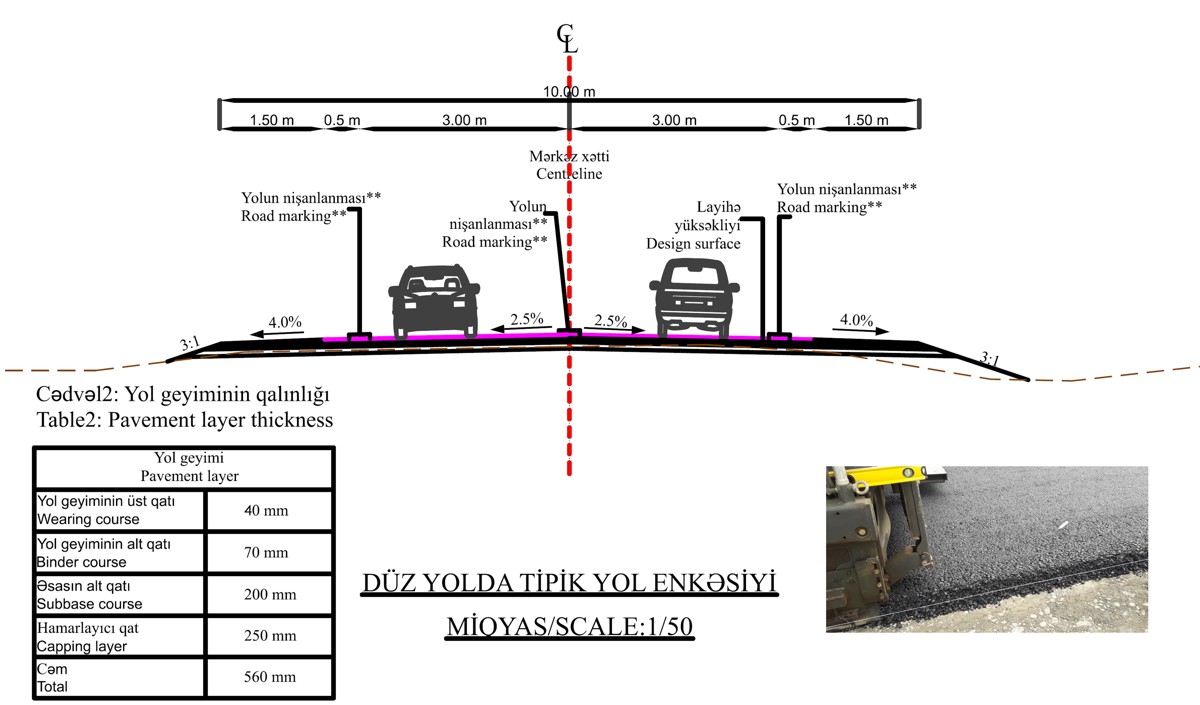

- Alpi Road (Rehabilitation Project in Azerbaijan)

- Pavement: hot mix asphalt (HMA) paving materials from suitable mixing plants (binder and wearing courses).

- Design choice of the pavement consistent with the availability of nearby suitable hot mix asphalt plants.

- Pavement: hot mix asphalt (HMA) paving materials from suitable mixing plants (binder and wearing courses).

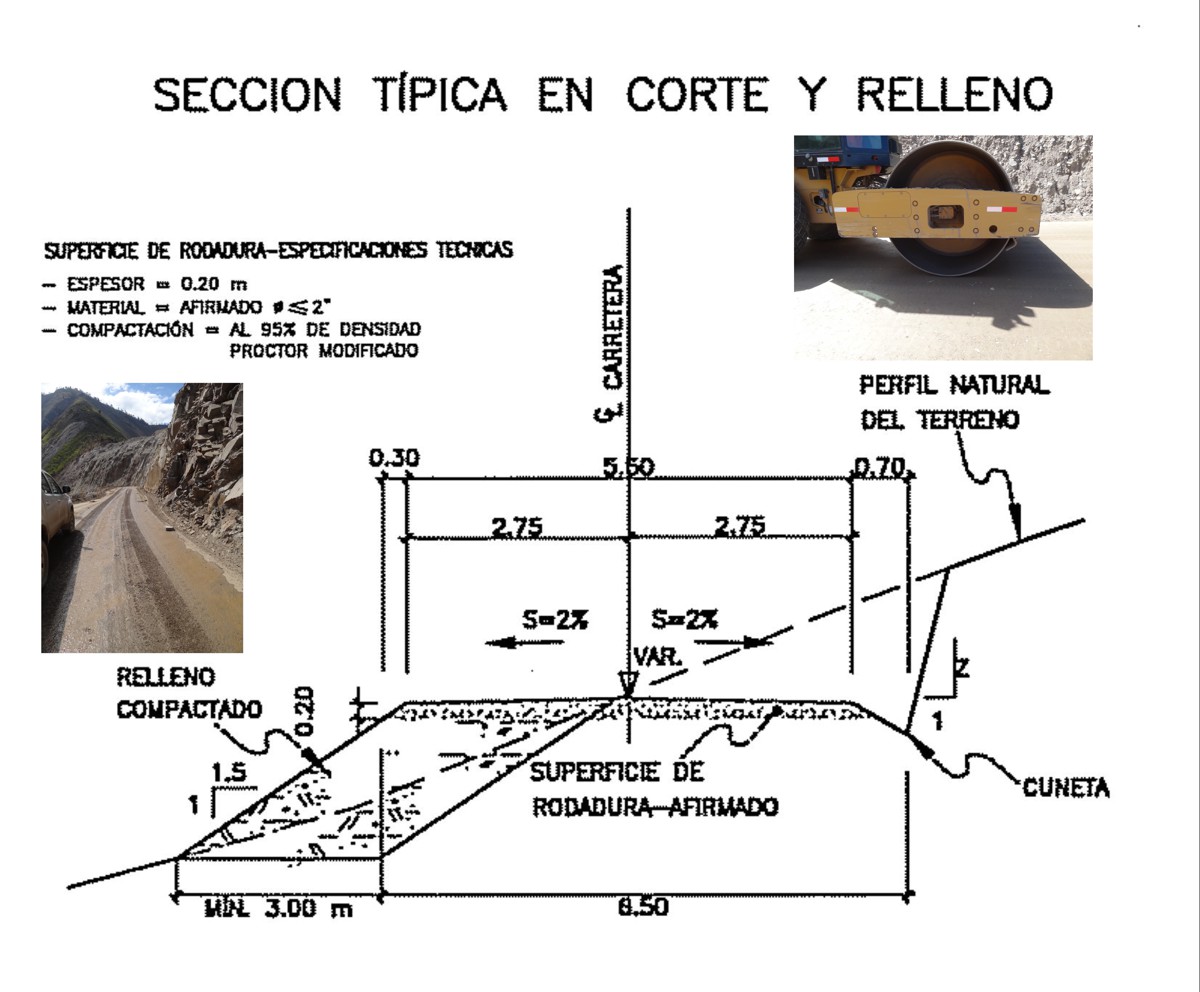

- Ccochac – Barropata Road (Construction Project in Peru)

- Pavement: unbound pavement materials produced in mobile crushing and screening plants (wearing course in Afirmado)¹.

- Design choice of the pavement consistent with the low volume of traffic expected, construction site access difficulties and unavailability of nearby suitable production plants.

- Pavement: unbound pavement materials produced in mobile crushing and screening plants (wearing course in Afirmado)¹.

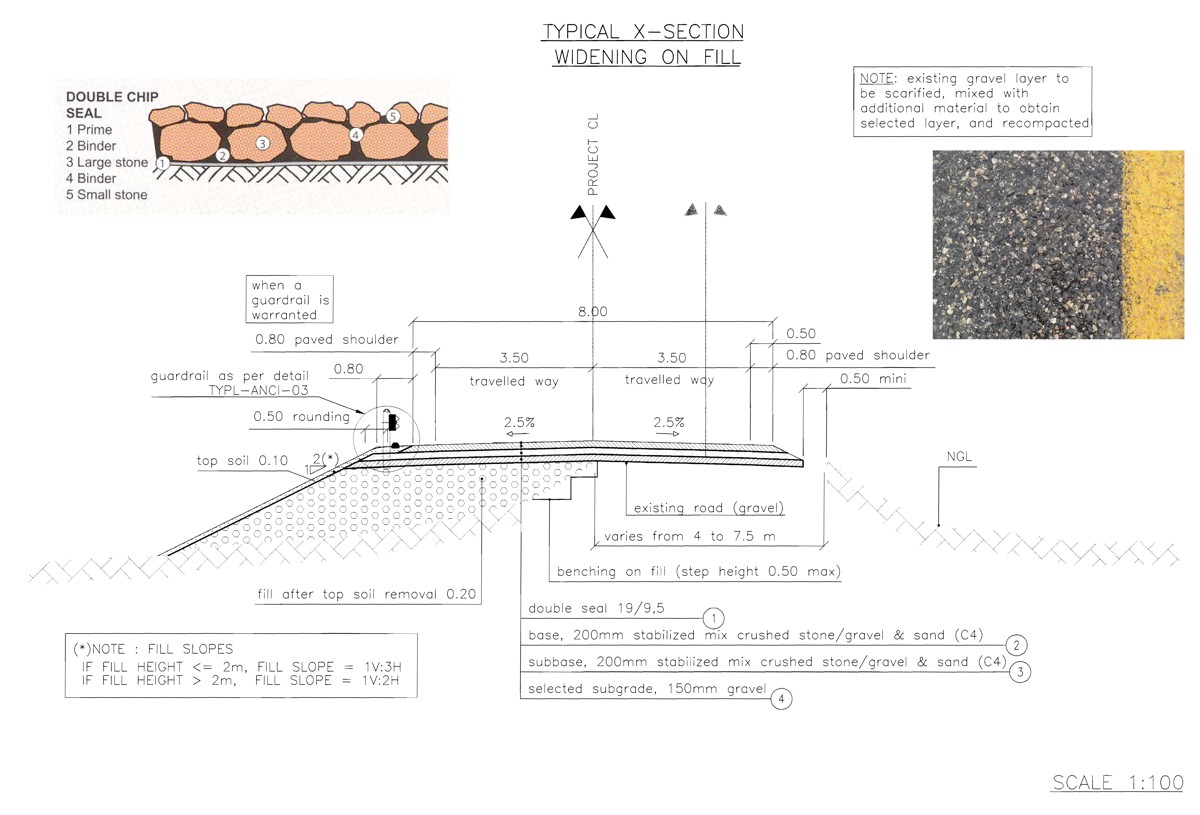

- Montepuez – Ruaca Road (Upgrading Project in Mozambique)

- Pavement: bitumen bound pavement materials produced by on-site process (wearing course in Double Chip Seal)².

- Design choice of the pavement consistent with the unavailability of nearby suitable hot mix asphalt plants, the availability of aggregates with good physical-mechanical properties near the construction site and the availability of qualified workmanship for this application.

- Pavement: bitumen bound pavement materials produced by on-site process (wearing course in Double Chip Seal)².

Conclusions

A country’s rural road network is made up of “non-motorized (rural) roads” (typically footpaths and cattle trails) and “motorized (rural) roads”, whose purposes are:

- service roads for the local farms and agro-forestry-pastoral activities;

- connecting roads between villages and small towns;

- connecting roads to national highways, main transport networks and urban areas;

- improve accessibility to health services, education, markets, etc., thus revitalizing the quality of life of rural communities and the economy of all country (Figures 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18: small rural villages in Mozambique, Peru, Azerbaijan and Laos).

By requiring the need for structural transformations and new sustainable infrastructures, it is clear that the opportunity for economic growth in developing countries, highlight the great importance of the rural-urban linkages. Therefore, such linkages play a fundamental role in the interest of the whole country.

In order to ensure acceptable performance and durability requirements (and acceptable costs) of road upgrading, rehabilitation and reconstruction projects, during the initial stages all the possible design options shall be explored and the specificities found, within the investigation framework, shall be taken into account, and suited as much as possible.

In this regard, the knowledge of materials and construction technologies locally available is a crucial step required to address properly the proposed projects and support their success.

Indeed, especially in the case of rural roads with low traffic volume, the construction and maintenance costs required for roads conforming to the standards and technologies in use in the developed countries could be prohibitive and, finally, difficult to sustain.

Article by Andrea Pugliaro, Senior Materials Engineer, Independent Consultant (Geologist and Civil Engineer)

¹ Compacted layer of granular material – with specified properties and gradation – that directly bears traffic loads. It must have an adequate amount of cohesive fine material to hold the particles together.

² A thin layer of heated liquid bitumen is sprayed on the treated road surface, followed by the spreading of a first layer of larger aggregates and compaction with rollers. Thereafter, a second thin layer of heated liquid bitumen is sprayed, followed by a second application of aggregates and compaction with rollers (the procedure for the second layer is the same, but with a smaller aggregate, about half the size of that used in the first layer).