Metal Steam Turbine Blades can now be 3D Printed

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory became the first to 3D-print large rotating steam turbine blades for generating energy in power plants.

Led by partner Siemens Technology, the U.S. research and development hub of Siemens AG, the project demonstrates that wire arc additive manufacturing is viable for the scalable production of critical components exceeding 25 pounds. These parts have traditionally been made using casting and forging facilities that have mostly moved abroad.

“There’s now a realization that we cannot get low-volume castings and forgings that exceed 100 or 200 pounds from the domestic supply chain,” said Michael Kirka, lead research and group leader for the Deposition Science and Technology group at ORNL. “It’s put us in an untenable position, especially as we see how international conflicts have affected the international movement of critical supplies.”

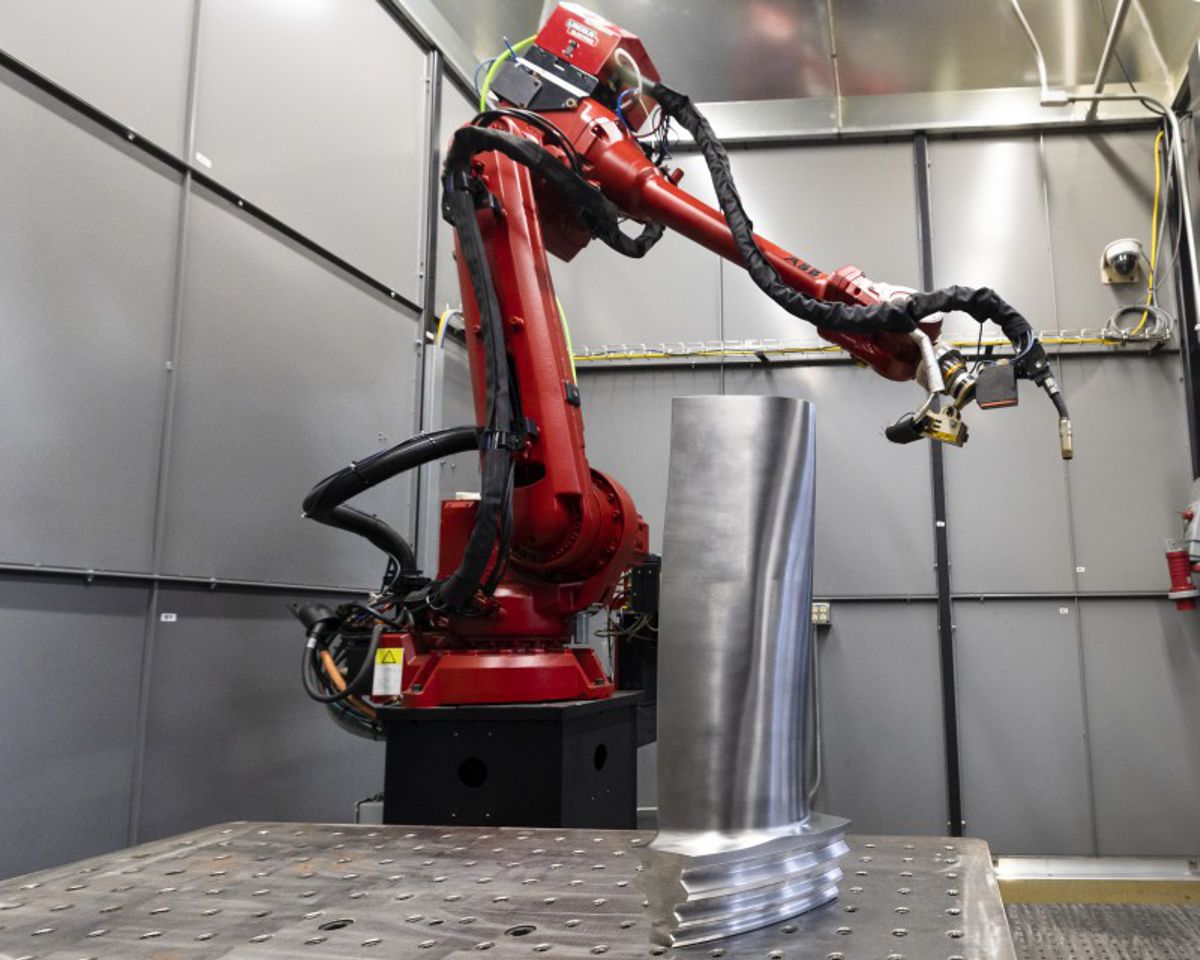

Wire arc additive manufacturing uses an electric arc to melt metal wire in a process controlled by a robotic arm. Thin layers of metal are gradually built up into the desired shape. Once printed, the part is machined to meet the final design requirements. The wire-arc technology used to manufacture the turbine blade was developed in collaboration with Lincoln Electric under a cooperative research and development agreement.

Because wire arc manufacturing is based on welding technology, it is easily used for repairing existing parts. This could allow companies like Siemens Energy, a Siemens sister company that is also a partner in the project, to more easily maintain and upgrade equipment under service contracts with electric utilities.

When the Siemens wire arc research began in 2019, it focused on component repair. However, the scope expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the wait for new cast steam turbine blades stretched to two years. Then the project broadened to include printing entire replacement parts, because these types of turbine engines are versatile enough to use in gas, coal and nuclear power plants, Kirka said.

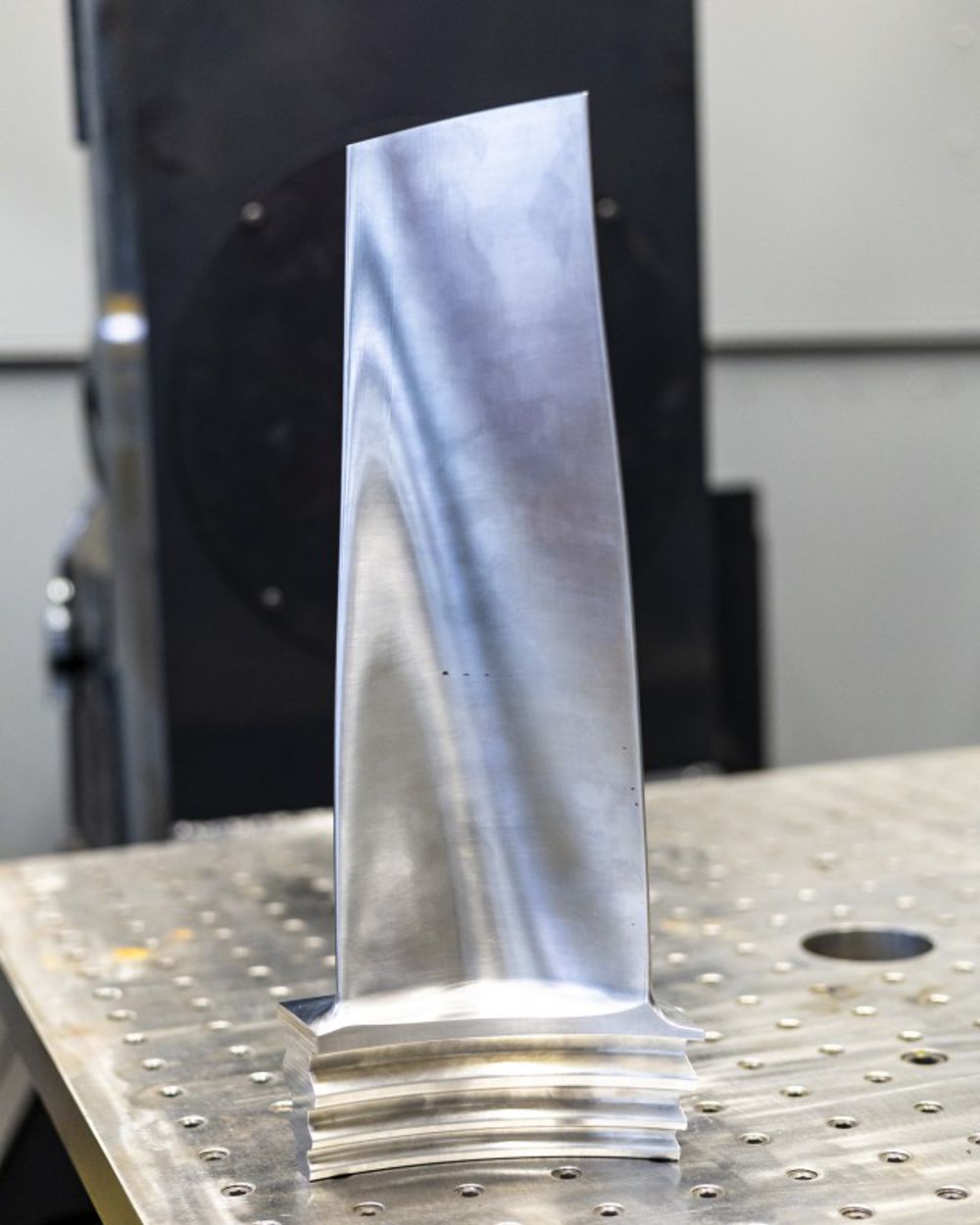

ORNL researchers experimented with materials and developed better ways to evaluate the mechanical performance of printed parts. The large steam turbine blade, made from a steel alloy, was the culmination of these efforts.

“The original intent was to just print 25% of the top section of the blade,” said Anand Kulkarni, senior principal key expert for Siemens Technology. “But when we saw the potential of the wire arc setup at ORNL, we thought we could do the whole blade in one build. The capability to scan the part while it was being built gave us the right information that could be fed to our machining staff and enabled us to reduce production time.”

While the wait for large castings and forgings has decreased to seven or eight months, ORNL was able to print the blade in 12 hours. Including machining, a blade can be finished in two weeks, Kulkarni said.

Although wire arc is a prominent 3D-printing technology, it had not previously been used to make a rotating component of this scale, Kirka said. Turbine blades typically have no parallel or perpendicular surfaces. Their contoured curves narrow toward the tip. “Being able to print and finish something with no locating features is a challenge,” he said. In addition, heavier parts of this size cool more slowly, adding sensitivity to the speed and order of depositing the layers.

After machining the part, Siemens is working with the Electric Power Research Institute on non-destructive evaluation and testing. “We’re still looking at the properties side of things to see how results compare with traditional methods,” Kulkarni said. For repairs, however, the properties don’t have to be identical: The current challenge is just keeping engines running and avoiding downtime, he said.

“But if the quality of the part is good, that opens doors to more on-demand manufacturing,” Kulkarni said. “And this case study opens the envelope to large components.”

A key advantage to 3D printing is that it frees companies from dependence on specific manufacturing tools they don’t control, such as moulds made by a single casting house for a single design. Many of the large-scale components in today’s turbines are several decades old, but because of closures and industry offshoring, the tools that created them have effectively disappeared, Kirka said. 3D printing offers a more reliable alternative because it can replicate any design.

Other ORNL researchers who contributed to the project, which was funded by the DOE Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, include Ryan Duncan, Luke Meyer, Chris Masuo, Chris Ledford, Patxi Fernandez-Zelaia, Andrzej Nycz and Andres Marquez Rossy.

The steam turbine blade was printed in DOE’s Manufacturing Demonstration Facility. The MDF, supported by DOE’s Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies Office, is a nationwide consortium of collaborators working with ORNL to innovate, inspire and catalyse the transformation of U.S. manufacturing.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States. The Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.