All Aboard the Autonomous Hybrid Road Rail Revolution

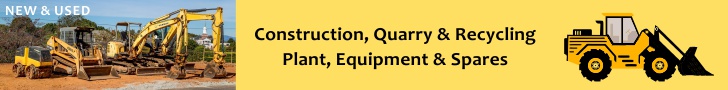

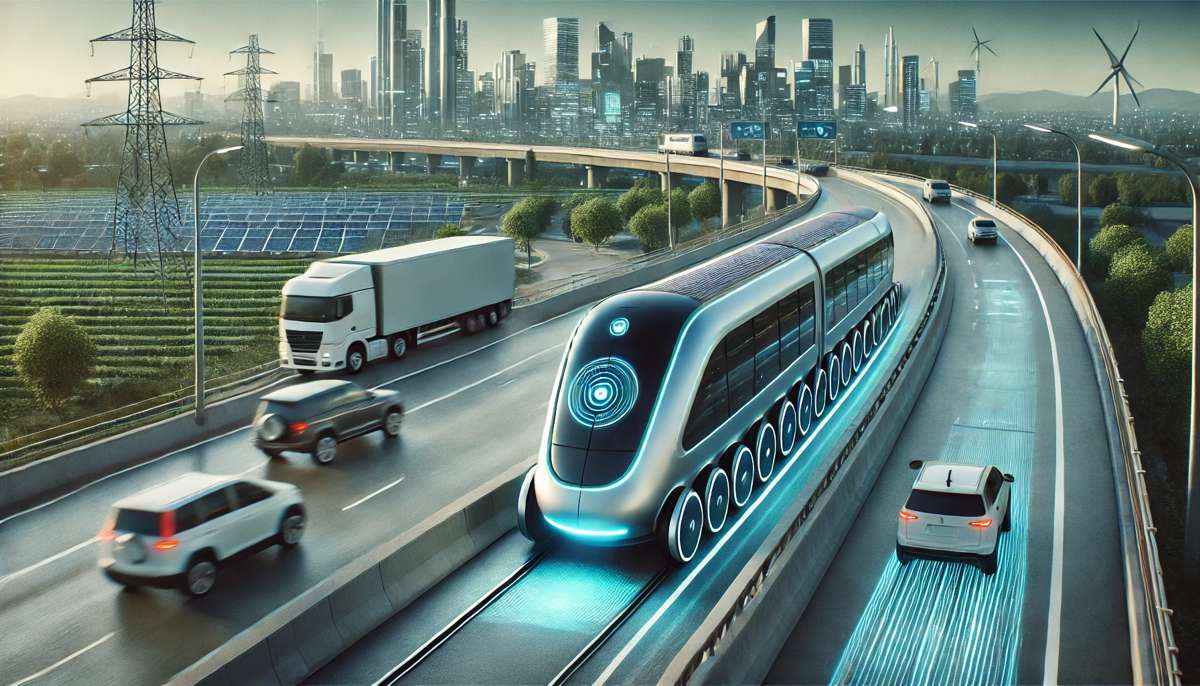

Imagine a world where a freight truck drives itself to a rail junction, slides onto the train tracks, and speeds off under the guidance of artificial intelligence. No manual coupling, no waiting for a locomotive – just a seamless handover from road to rail.

This vision of hybrid road-rail transport, once science fiction, is edging closer to reality. Across continents, engineers and policymakers are reimagining how we move people and goods. Their goal is bold: harness automation and AI to create a smarter, autonomous railway network that works in tandem with highways and cities.

It’s an ambitious undertaking that could transform 21st-century transport as profoundly as the steam locomotive did two centuries ago.

The Current System

Today’s railway and freight transport systems, while reliable, are rife with inefficiencies. Most passenger and freight trains run on fixed timetables and rigid routes planned well in advance. This rigidity means that when demand changes or disruptions occur, the system struggles to adapt. Freight in particular often faces circuitous journeys – a shipping container might be loaded on a train, only to sit idle in a switching yard awaiting assembly into a longer convoy. Such stop-start logistics waste time and capacity. In fact, freight can spend hours or even days being sorted and reassembled in rail yards, significantly lengthening delivery times. Every delay has a ripple effect: a late-running train can hold up others on single-track lines, and missed connections can idle valuable assets.

A major challenge is the first and last mile problem. Trains excel at moving bulk cargo or lots of passengers between hubs, but they can’t roll up to a factory dock or a city centre high street. That task falls to lorries and vans, creating an extra layer of transfers. The need to shift between road and rail adds cost and complexity, often making road transport the default choice even for long distances. It’s no surprise that trucks dominate freight movement in many regions today. In the United States, for example, nearly 75% of freight (by value) travels by road, while rail handles only a fraction. This is paradoxical, since rail is inherently more energy-efficient for heavy loads – yet flexibility and door-to-door convenience give road haulage the edge under current systems. Europe faces its own inefficiencies: fragmented national rail networks, varying standards, and the priority given to high-speed passenger trains on shared lines all constrain freight. In countries like the UK and France, fast passenger services crowd the daytime schedule, forcing slower freight trains to run at night or wait on sidings. The result is underutilised capacity and a transport sector that emits more carbon and costs more money than it should.

From congested highways to overbooked rail corridors, the status quo clearly leaves much to be desired. Ageing signalling systems and manual control still underpin many rail operations, meaning trains can’t respond dynamically to real-time conditions the way, say, ride-sharing cars can reroute on the fly. As demand for freight grows and commuters expect ever more punctual service, the cracks in the current model are showing. The industry is ripe for innovation – and that’s where automation and AI-driven solutions come into play.

An Automated Railway Network that Allows Independent and Efficient Users

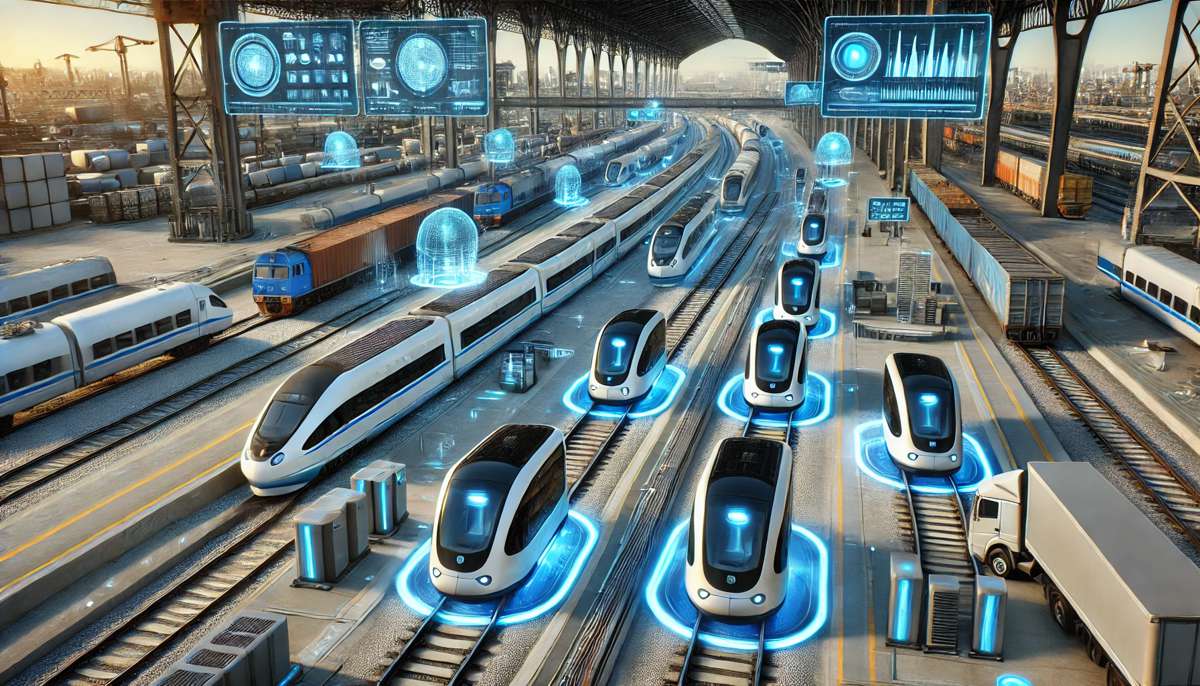

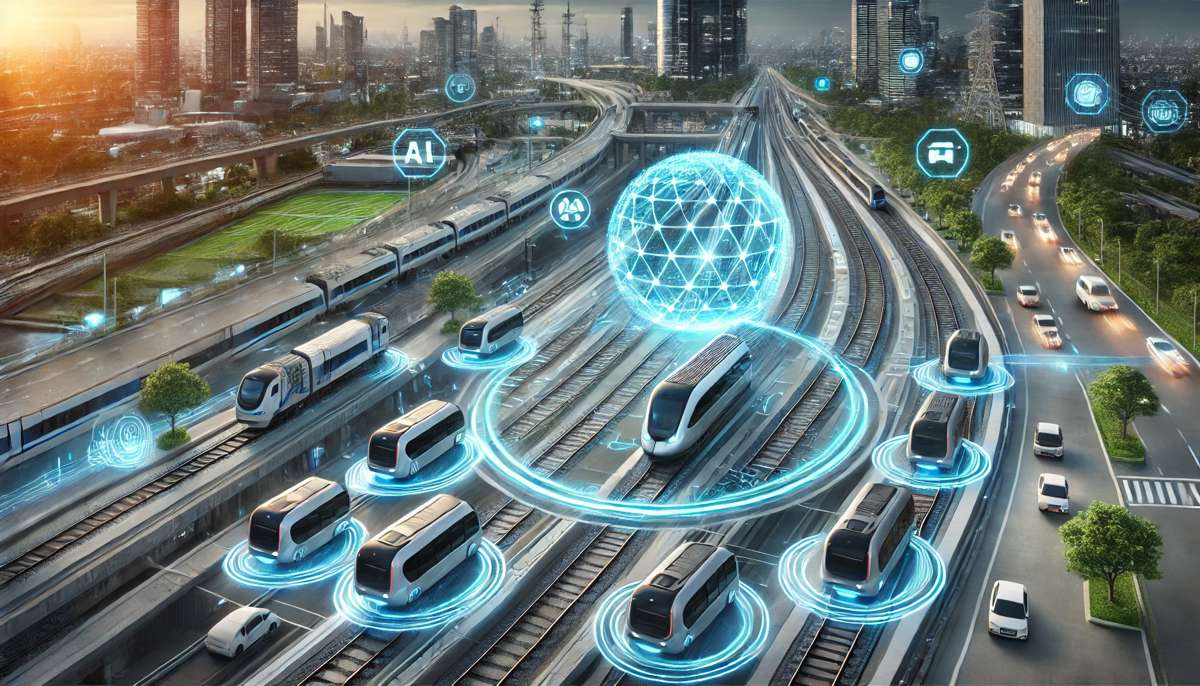

Enter the concept of an automated, AI-optimised railway network – a system where trains drive themselves and routing is managed by smart algorithms rather than static schedules. In this future, the railway behaves more like a busy digital highway: autonomous train units continuously communicate with network control AI, which choreographs their movements with precision. Instead of one central operator deciding which train runs where, the network could accommodate independent users – multiple companies or entities running their own automated vehicles – all coordinated by a real-time digital “conductor” for optimal flow.

Such a network would be governed by advanced signalling and traffic management software. Using sensors, wireless communication, and machine learning, the AI would allocate track pathways on the fly, avoiding conflicts and squeezing maximum capacity out of the rails. Already, we see early steps toward this vision. Around 60% of rail infrastructure managers in a recent international survey said they’re using AI to plan efficient train routes and reduce disruptions through centralised, automated traffic management in real time. Instead of rigid timetables, an AI dispatcher can react to current conditions – if one route is blocked, it instantly sends trains along alternate lines, much as internet traffic is rerouted around a busy node. Each train (or pod) becomes an intelligent agent too, constantly updating its position and speed to the network brain, which orchestrates every movement with split-second timing.

The benefits of automating rail operations are significant. Punctuality and throughput could dramatically improve. Studies indicate that automated trains can reduce delays by up to 30% compared to traditional human-operated systems. By leveraging predictive algorithms and adaptive control, an AI rail network would minimise the domino effect of holdups – if a train is slowing down, following vehicles automatically adjust rather than coming to a standstill at a red signal. Safety would likely improve as well, with AI eliminating human errors and responding to hazards (like obstacles on the line) faster than a person could. Crucially, automation allows for 24/7 operation with less downtime. Just as server farms process data around the clock, driverless trains could run through the night, with only brief stops for maintenance or battery recharging. This always-on capability means higher asset utilisation – more miles per train per day – and ultimately a more efficient network.

Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of an AI-driven rail system is how it opens the rails to independent and flexible use. Today, access to rail infrastructure is often limited to national operators or pre-scheduled slots. In an automated scenario, any authorised user – whether a major rail company or a small logistics start-up – could dispatch a vehicle onto the network on demand. Intelligent routing algorithms would slot that vehicle into the traffic flow, maintaining smooth operations for everyone. It’s a bit like air traffic control, but potentially even more agile: a digital platform coordinating myriad vehicles, from long freight trains to single-passenger pods, each “speaking” to the network and to each other. By removing the traditional constraints of fixed schedules and exclusive track occupancy, the railway becomes a shared, dynamic backbone for transport, much like the internet is for information. This level of openness and efficiency could fundamentally change who uses railways and how.

The Vehicles that Could Make Use of an AI Rail Network

What kinds of vehicles would roam this intelligent rail network? The vision calls for a new generation of hybrid train pods – versatile, autonomous vehicles capable of both road travel and rail operation. Imagine a sleek electric pod the size of a bus or lorry trailer that can drive itself on ordinary streets, then, upon reaching a railway access point, extend flanged wheels or otherwise lock onto rails and accelerate down the track. These pods would function as autonomous road vehicles for first and last-mile transport and as train cars once on the main line. It’s a unifying concept: door-to-door capability with the efficiency of rail for the long haul.

On the freight side, this idea is already being prototyped. In the U.S., a tech firm called Glïd has developed an autonomous, electric road-rail vehicle specifically to carry standard truck trailers. It can literally scoop up a fully loaded semi-trailer and place it onto rail wheels – no driver or locomotive needed. In 2023, Glïd secured a landmark partnership to test these units on a shortline railroad, the first arrangement in the United States granting an autonomous vehicle access to active rail tracks. This development means a truck trailer could roll off the highway at a logistics park outside a city, attach to a Glïd pod, and be whisked hundreds of miles on electrified rails, then delivered by road for the final stretch. Meanwhile, California-based start-up Parallel Systems (founded by former SpaceX engineers) is reimagining freight trains as platoons of small, individually powered rail cars. Each Parallel Systems vehicle carries a single shipping container and can join up with others to form a platoon or mini-train as they travel. Because they don’t rely on a locomotive, these units can even split off to different destinations en route, much like lorries taking different highway exits. The flexibility is unprecedented – no more waiting to gather 100 cars in a yard before departure. A few container pods can set off as soon as they’re loaded, and others can join along the way. Early tests suggest this approach enables more responsive service and new routes, without the need to accumulate massive volume per train.

Passenger transport could also be transformed by such vehicles. Picture calling an automated “rail taxi” via a smartphone app. A pod – perhaps seating a handful of people – drives to your home or office, picks you up, then proceeds to the nearest rail line and docks onto it. On the tracks it might merge into a convoy for efficiency, travelling at high speed to your destination city. Once there, it detaches and drives on normal roads to drop you at your final stop. This door-to-door rail service would blur the lines between personal car travel, ride-share, and traditional train journeys. In fact, a prototype of a six-seat autonomous pod was unveiled in Dubai in 2018, demonstrating the feasibility of small modular vehicles (or “pods”) that can link together in transit. Those Dubai pods were road-based, but the same principle could apply to rail: multiple small units could couple into a “train” when advantageous, then uncouple to scatter to different neighbourhoods. For commuters, such pods promise convenience without the need to make multiple transfers. For transit agencies, they offer a way to provide service even in off-peak times or low-density areas – send a single small pod rather than a mostly-empty train, and join it to others later to share track space efficiently.

Whether ferrying people or goods, these hybrid vehicles would share key features. They’d be battery-electric for zero emissions and quiet operation, with autonomous driving enabled by arrays of cameras, LiDAR and other sensors, plus V2X (vehicle-to-everything) communication to stay in constant contact with the rail network’s AI control. Standardisation will be crucial: pods must be able to safely navigate onto tracks, perhaps at special on-ramps or through automated guidance systems that align them properly. They also need to interface with rail signalling and each other for cooperative movement. But if those challenges are met, the result is powerful – a fleet of modular vehicles that can use existing road and rail infrastructure interchangeably. From a logistics perspective, a shipping container might be picked up at a port by a self-driving pod, join a train convoy for cross-country travel, and be deposited at a factory’s doorstep, all without a single manual lift. For passengers, a long journey might feel like taking one continuous vehicle the whole way, even if that vehicle “morphed” from a car to a train halfway. These innovations could unlock rail transport’s latent potential, finally bridging the gap between the flexibility of road transport and the efficiency of rail.

Infrastructure Changes

To make an AI-driven, hybrid rail network possible, substantial infrastructure upgrades and new construction will be needed. The railways of the future won’t just be iron rails and wooden sleepers; they’ll be smart, connected corridors bristling with sensors and communication tech. First and foremost, signalling systems must evolve. Traditional colour-light signals and fixed blocks will give way to advanced digital signalling that interfaces directly with autonomous vehicles. Much of the world is already moving in this direction – for example, Europe’s newest rail lines are adopting the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) with in-cab digital signalling. A fully automated network would likely use moving-block systems (where safe distances between trains are managed dynamically) to allow many more vehicles on the line at once, safely. Implementing this requires upgrading tracks with sensors (or equipping each vehicle with the ability to continuously report its position and speed). The communication backbone will be critical: expect dedicated wireless networks along tracks (such as 5G or a rail-specific broadband system) to keep every train pod in sync with central control. Imagine a continuous data handshake as a pod transitions from road (using public cellular networks) to rail (switching to a railway’s private network) without dropping the connection. This kind of robust, ubiquitous connectivity is essential for real-time coordination.

Stations and terminals will also see dramatic changes. To enable smooth road-rail transitions, new kinds of interchanges must be built. These might look like a cross between highway rest stops and rail freight yards – entry/exit ramps where autonomous pods can drive on and off the track. Designing such hubs means modifying track layouts: perhaps a dedicated lane runs alongside the railway for a short stretch, allowing a pod to align its wheels with the rails and merge into the traffic flow. Freight terminals might be equipped with automated cranes or ramps so that trailer-carrying pods (like the Glïd units) can load and unload without human intervention. Passenger stations could have designated docks for pods to pull in and let riders board, before the pod merges onto a main line. All this calls for significant construction: new track connections, reinforced pavement at rail interfaces, and possibly electrified charging infrastructure at these interchange points. In city centres, existing stations might need retrofitting to accommodate autonomous pods alongside conventional trains during a transitional period.

Energy infrastructure is another crucial piece. As vehicles and rail operations electrify, the rail network becomes as much an electrical grid as a transport route. Many rail lines (especially freight corridors in North America, or rural lines elsewhere) aren’t electrified and rely on diesel traction. An automated, sustainable network would push for widespread electrification – whether via overhead lines, third-rail systems, or fast charging stations for battery-equipped pods. This might entail stringing new catenary wires on routes that currently lack them, or installing charging pads at regular intervals where a pod can top up its battery en route. The power demand will increase, so integration with national grids and renewable energy sources will be important. One can imagine solar panels along railway rights-of-way or wind turbines dedicated to powering electric rail hubs. Additionally, robust backup systems need to be in place. Fail-safe designs (such as redundant communications and the ability for vehicles to safely coast to a stop if signals are lost) will be mandatory to satisfy safety regulators and public concern.

Behind the scenes, digital infrastructure will be just as vital as physical upgrades. Rail control centres will start to resemble air traffic control rooms or data centres, with servers crunching real-time data from across the network. Sophisticated dispatching software – effectively the “AI dispatcher” – will need development and constant refinement. Cybersecurity also becomes paramount: the rail network must be protected against hacking or interference, since a malicious attack on a central control system could have serious consequences. This means investing in secure communication protocols and fail-safes that can override or isolate parts of the network under threat. The construction industry and tech firms will work hand in hand: laying fiber-optic cables along tracks, installing trackside IoT devices (for monitoring track conditions, weather, etc.), and building new data facilities for rail operators. In short, transforming the rail infrastructure for AI is a holistic effort, encompassing everything from concrete and steel to code and cloud servers.

Economic Impacts

The economic implications of a hybrid AI rail network are vast. At the highest level, such a system promises major efficiency gains and cost savings for transport operators, businesses, and ultimately consumers. By optimizing train routing and spacing in real time, an AI-managed network can carry more traffic on the same infrastructure. Research by Europe’s rail industry indicates that smarter capacity planning and automation can boost network capacity by as much as 7–9%. In practical terms, that means moving more trains (or pods) per day on a given line without laying a single new track – effectively squeezing more value out of existing assets. Over time, that extra capacity translates to billions in economic benefit, whether through increased freight volume (more goods delivered faster) or improved commuter service (attracting more passengers, thus more fare revenue and productivity gains from reduced travel delays).

Automation also tends to drive down operational costs. Today’s railways spend a significant portion of their budget on labour (train drivers, crew, dispatchers) and fuel. With autonomous operation, the labour cost per train-kilometre drops: one control centre team can oversee dozens of self-driving trains, instead of needing one or two drivers per train. At the same time, the switch to electric propulsion and AI-optimised driving will cut energy expenses. Automated trains can be programmed to eco-drive – smoothing acceleration and braking to reduce energy use, and timing their speed to avoid unnecessary stops. Such efficiencies in energy consumption lower the cost per journey. Maintenance costs may fall as well: AI systems will continuously monitor vehicle health and track conditions, enabling a shift from reactive repairs to proactive maintenance. Fixing issues before they cause breakdowns means less expensive damage and fewer service interruptions. Over a year, that could save rail operators significant sums and improve asset longevity.

For freight shippers and logistics companies, a more nimble rail network opens up new business models. Rail could start to compete in areas it traditionally ceded to road haulage – like fast delivery of smaller consignments or just-in-time distribution. By running smaller autonomous units cost-effectively, the rail network would enable “on-demand freight” analogous to on-demand ride services. A factory might dispatch a single container via a rail pod in the evening and have it arrive hundreds of miles away by morning, without paying for an entire train or waiting for a weekly service. This increases logistical flexibility and could reduce warehousing costs: if deliveries can be scheduled more precisely and frequently, companies don’t need to stockpile as much inventory. Consumers might feel the benefits through more resilient supply chains (fewer stockouts and delays) and potentially lower prices as shipping becomes more efficient.

On the passenger side, if rail becomes more convenient and tailored (thanks to first/last-mile pods and more frequent services), ridership is likely to grow. More people choosing trains over cars or planes for certain trips has positive economic knock-on effects: less road congestion translates to time saved (which is economically valuable), and possibly less road maintenance spending for governments. There’s also an urban development angle – improved rail connectivity can boost property values and spur investment around station areas. If autonomous pod stations pop up in smaller towns or logistic parks, those locations might suddenly become more attractive for businesses, knowing they have a direct pipeline for transport.

At a macro level, shifting significant freight volume from road to rail could reduce national expenditures on highway construction and repair. Heavy lorries are notoriously hard on roads; by offloading some of that freight to rails (which have far greater carrying capacity and longevity), governments could save on road upkeep and expansion, freeing public funds for other investments. Environmental cost savings (discussed more below) also have economic value – healthier populations and less environmental damage mean less strain on healthcare and disaster relief budgets. In sum, an AI rail network promises to streamline the transport sector, making both passenger mobility and goods delivery cheaper and more efficient. While there are upfront costs to build this system, the long-term payoff – a leaner, faster, more reliable transport network – represents a compelling economic opportunity for forward-looking nations and investors.

Regulatory Hurdles

Revolutionising rail transport with AI and autonomous vehicles isn’t just a technical challenge – it’s also a regulatory one. Every country has built up layers of safety rules, technical standards, and operational protocols over decades of traditional railroading. Adapting or overturning these to accommodate driverless trains and mixed road-rail vehicles will require careful navigation by industry and regulators alike. Key issues include certifying the safety of AI systems, updating laws that assumed a human operator would always be in charge, and coordinating standards internationally so that new systems can cross borders. Different regions are approaching the challenge in their own ways:

- Europe: European regulators are pushing for a harmonised approach through initiatives like the EU’s rail research programmes, but the reality is that each country’s safety authorities must be convinced. Automation is being tested (for example, Deutsche Bahn and SNCF have trial projects for automated trains), yet getting approval for regular driverless operation on national rail networks is a tall order. Standards such as the Common Safety Method will need new provisions for AI decision-making and obstacle detection. Cross-border interoperability is crucial in Europe – an autonomous train might travel from France to Germany, so the systems must be compatible. The EU is likely to develop common rules for autonomous trains, but reaching consensus takes time. In the meantime, full automation might first roll out on dedicated lines (for instance, isolated freight corridors or in rail yards) where conditions are easier to manage. Europe’s strong rail unions and public sensitivities around safety mean regulators must move prudently, probably requiring that autonomous trains initially have staff on board as a fallback during a transitional phase.

-

United Kingdom: The UK, having significant rail traffic and a mix of old and new infrastructure, faces similar challenges. Any shift to AI-driven trains will be scrutinised by the Office of Rail and Road (ORR), which will demand evidence that these systems are as safe as human-driven trains. Britain has some experience with automation (the Docklands Light Railway in London has been driverless since the 1980s, and the Thameslink heavy rail route uses automated control under driver supervision in central London), but extending that to mainline intercity or freight trains is unprecedented. Regulatory updates would be needed for signalling rules, requirements for onboard staff, and cybersecurity standards. The government’s ongoing rail reforms could open the door to more innovation-friendly regulations, but public opinion will matter too. Any incidents during testing could set back trust. The UK may therefore take an incremental approach: perhaps starting with automated trains that still have an attendant on board (much like some driverless metros do initially), then moving to full autonomy once the public and regulators are comfortable.

-

United States: In North America, regulatory hurdles are high. The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) currently has regulations assuming a crewed train, and while Positive Train Control (PTC) systems are now in place as a safety net, the idea of removing the crew entirely is still far from acceptance. U.S. freight railroads in particular operate under strict safety rules and have powerful labour unions. In recent years, there have been debates about mandating two crew members in every locomotive for safety, which shows the prevailing sentiment. To deploy autonomous trains, either new regulations would need to be written or the FRA would have to grant waivers for pilot projects. We’re seeing the first steps: the FRA has allowed limited testing of remote-operated and autonomous technologies on shortline railroads (like the Glïd trials on the PVJR line). But broader adoption will likely require demonstrating, over millions of kilometres, that AI can handle scenarios like road crossings, trespassers on tracks, and complex signalling interchanges as well as or better than humans. Liability and insurance also loom large in the U.S. – if an autonomous train were involved in an accident, the legal implications could be messy until laws catch up. The path forward may involve phased implementation (e.g. autonomous operation only in low-risk areas or when carrying freight that isn’t hazardous) and strong oversight. Ultimately, U.S. regulators will be guided by data – if the industry can prove these systems reduce accidents and incidents, the FRA will come on board, but that proof will have to be ironclad.

-

China: In contrast, China’s regulatory environment, while still concerned with safety, can be more top-down and fast-moving when a technology aligns with national goals. China has already broken ground with the world’s first fully driverless high-speed railway, opened in 2019 for the Beijing–Zhangjiakou route. Having demonstrated that, China is likely to aggressively pursue automation in both passenger and freight realms. The government can set directives for its state-run rail companies to adopt AI and allocate significant resources to the effort. Regulations in China will probably be crafted in parallel with the technology rollout – rather than waiting for years of debate, standards might be developed by committees of engineers and officials and quickly mandated. That said, China will still need to ensure safety of autonomous operations across a vast and heavily used network. Issues like standardising communication between autonomous trains and existing ones, and upgrading older routes to support automation, will be major tasks. Internationally, if Chinese companies become exporters of autonomous rail technology, their systems will need to meet global standards – so China is also participating in forums like the International Union of Railways to help shape those standards. In summary, China’s regulatory hurdle is less about whether to do it (the decision seems already made in favour of automation) and more about how fast it can scale up without compromising safety on its huge rail system.

Adoption Challenges and Public Perception

Beyond technical and regulatory barriers, there’s a human factor: industry adoption and public perception will greatly influence how quickly an AI rail network becomes reality. Even the smartest technology can stall if people don’t trust it or if key stakeholders see more risk than reward in changing the status quo. Gaining the buy-in of rail workers, freight customers, and the general public is as important as getting the technology right.

One major challenge lies with the workforce and organisational culture. Railways have a proud, long-standing tradition of skilled human operation – from the driver in the cab to the signaller in the control room. The prospect of handing critical duties over to algorithms can understandably trigger resistance. Labour unions worry about job losses or the devaluation of expertise. In Europe and the U.S., unions have already signalled opposition to driverless trains, primarily over safety and employment concerns. Retraining and role evolution will be key to easing these fears. Rather than eliminate jobs, automation could shift them – for instance, train drivers might transition into fleet managers who oversee multiple automated trains remotely, or into maintenance and supervisory roles ensuring the AI is functioning correctly. Companies will need to invest in upskilling programs to help staff adapt to new roles (such as managing robotic systems or data analysis for train performance). It’s a delicate balance: rail companies must show they can achieve efficiency gains and preserve good jobs by redefining them. Early collaboration with unions, as seen in some European trials of automation, can help – involving employees in the development process makes the technology feel less like an outside imposition.

There’s also inertia and risk-aversion within rail management. Many rail operators operate on thin margins and prioritise reliability; they might be hesitant to be first movers with unproven tech. The initial costs of adopting AI and autonomous pods – purchasing new vehicles, installing new systems, training staff – are significant. Without clear government support or pressure (or compelling competitive reasons), some incumbents might prefer to wait and see. This was evident in the case of Glïd’s road-rail pod: early on, the startup struggled to find a railroad willing to let an autonomous vehicle run on their tracks, encountering what the CEO described as a “stream of doubtful dialogue” from industry partners. Overcoming this skepticism required finding a visionary rail partner and proving the concept in a controlled trial. It’s likely that in many regions, smaller or more innovative players (perhaps a regional railroad or a private rail line) will adopt these technologies first, providing a proof of concept that larger, established operators can then follow once benefits are clear.

Public perception is another critical piece of the puzzle. How comfortable will people be knowing that the train barreling through their town or the one they’re riding on is controlled by AI with no human at the helm? It’s a new experience for many, even though driverless metros have been operating safely in cities like Paris, Dubai and Copenhagen for years. Building public trust will require a track record of safety and transparency about how these systems work. Paradoxically, many passengers already travel on autopilot-operated planes and automated airport shuttles without issue – so acceptance is largely a matter of familiarity and confidence. Surveys in some cities have shown that once riders experience a well-run driverless service, a majority come to view it positively. The key is ensuring that the transition period is handled carefully. One strategy is to introduce autonomous trains but still keep an attendant or driver on board initially to intervene if needed – this can reassure the public that there’s a human backup. Over time, as the technology proves itself (and perhaps as a new generation of passengers grows up used to autonomy), comfort levels should rise.

Effective communication and public education will also matter. Transport authorities and companies will need to highlight the benefits (e.g. “this new AI train service means your commute will be 10 minutes shorter and greener”) and explain safety features in simple terms. They might even give the public opportunities to interact with the technology in low-stakes settings, such as demos or simulations, to demystify it. Clear protocols for things like emergency stops or evacuations in an automated system should be communicated, so passengers know what to expect. Additionally, there’s the issue of cybersecurity and privacy – the public will want assurance that these trains can’t be hacked or tricked. High-profile cybersecurity guarantees and maybe even third-party audits or certifications could help bolster confidence.

Freight customers (like big manufacturing or retail companies) form another audience whose perception matters. They will ask: can this new system deliver my goods dependably and without hiccups? Initially, some may be reluctant to shift from trusty trucking contracts to an unproven autonomous rail service. Pilot programs and partnership projects (for example, a major retailer testing autonomous rail deliveries on a certain lane) could help demonstrate reliability. As one logistics executive put it, shippers care about cost, speed, and reliability – if the new rail system can match or beat trucks on those metrics consistently, trust will follow. It may take a few years of dual-running (using both old and new systems) before conservative customers are fully won over.

In short, change management is as vital as the technology itself. The rail revolution will need champions who not only design the systems but also engage with the people affected – the employees running it, the passengers riding it, and the businesses relying on it. By addressing legitimate concerns, providing training and new opportunities, and proving the concept step by step, the industry can foster an environment where automation is viewed not as a threat, but as the natural next step in rail’s evolution.

Sustainability Benefits

One of the most compelling reasons to pursue an AI-optimised rail network is the significant environmental benefit. Rail transport is already far greener per mile than road or air transport, and automation could amplify that advantage by making rail even more attractive and widely used. Shifting more transport onto electric rails and away from diesel lorries and planes could dramatically cut emissions in the transport sector. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, freight railroads currently account for just 2.3% of transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions – a tiny slice, given that transportation is one of the largest polluting sectors. This is because trains are about four times more fuel-efficient than trucks, meaning moving freight by rail instead of by road cuts greenhouse gas emissions by roughly 75% on average. In other words, rail is already the low-carbon option. If AI innovations make rail more flexible and accessible, enabling it to capture a larger share of freight and passenger miles, the overall carbon footprint of transportation will fall.

An automated rail network would likely be an electric rail network, further enhancing sustainability. Many proposed train pods and autonomous trains are battery-powered or draw power from electrified lines. As national grids incorporate more renewable energy, electric trains can effectively run on wind, solar, or hydro power. This creates a virtuous cycle: more rail use means more transport powered by clean electricity rather than fossil fuels. It also enables better use of energy; for instance, autonomous systems can charge vehicles during off-peak hours or when surplus renewable energy is available, balancing the grid. Additionally, AI can optimise energy use by smartly regulating speeds and timing to minimise energy consumption (coasting when possible, regenerative braking, etc.). The result is not only fewer emissions but also less energy waste.

There are also local environmental benefits. Fewer diesel trucks on highways mean lower emissions of nitrogen oxides and particulates that cause air quality issues around busy roads. Communities near major highways or ports could see reduced smog and soot if a chunk of freight shifts to zero-emission trains. Noise pollution might decrease too – electric trains and well-maintained track produce less noise than the roar of diesel truck engines on interstates. And with less road traffic, there’s potential for reduced urban congestion, which in turn cuts idling time for remaining vehicles and further curbs emissions. In city centres, if autonomous pods can replace some car trips (by offering a convenient alternative), it could contribute to cleaner city air and less road traffic noise, improving quality of life.

Moreover, land use and resource efficiency would improve. Rail can carry far more people or goods on a narrower corridor than highways can. By utilising rail capacity more fully, we potentially reduce the pressure to build new highways or expand airport runways (both of which have high environmental and land costs). Some road infrastructure might even be repurposed or downsized in the long run. Consider that one freight train can haul the load of hundreds of trucks; enabling more such trains through AI effectively means we don’t need to pave as many roads or mine as much material for asphalt and concrete to support heavy trucks. This represents a less visible but important sustainability win.

Finally, the data-driven nature of an AI rail network dovetails with environmental monitoring and management. The same sensors and systems that manage train movements could also track environmental metrics (like noise, vibration, or even trackside pollution levels) and help operators mitigate impacts in real time. For instance, if an autonomous freight convoy is passing through a populated area at night, the system might slightly reduce speed to lower noise, balancing operational efficiency with community well-being.

In summary, the hybrid AI rail network could become a cornerstone of sustainable transport. It offers a way to move more people and freight with dramatically lower emissions per unit, especially if powered by clean energy. In an era where governments and industries worldwide are striving to meet climate targets, boosting rail’s role is one of the most effective strategies. By marrying green technology (electric vehicles, renewable energy) with smart technology (AI routing, automation), the rail network of the future could help drive the decarbonisation of transport on multiple fronts – curbing climate change, reducing local pollution, and conserving resources.

New Business Opportunities

The advent of AI-driven rail networks and hybrid road-rail vehicles is not only an engineering revolution – it’s also a burgeoning business opportunity. As with any disruptive technology, it creates space for new players, services, and industries to emerge, while also challenging established companies to innovate. The ecosystem surrounding a hybrid AI rail network could be rich and varied, offering opportunities for tech firms, manufacturing, construction, energy, and more.

Consider the technology sector: developing the software and hardware for autonomous trains is a massive undertaking spawning start-ups and attracting investments. Companies at the nexus of AI, robotics, and transportation are already getting attention from investors. A striking example is Parallel Systems, the start-up founded by former SpaceX engineers to build autonomous electric railcars, which raised about $50 million in its first major funding round. Venture capital sees promise in these technologies, betting that they can upend a transport market worth hundreds of billions. Similarly, firms like Glïd are merging cutting-edge robotics with logistics and finding eager partners (their tie-up with a shortline railroad also brought them into the public markets via their parent company). We can expect more start-ups to tackle niches like AI scheduling software, vehicle-to-infrastructure communication, or battery systems tailored for trains. Beyond start-ups, big tech companies might also expand into this arena, supplying cloud computing power for rail data or AI algorithms for optimization – much as companies like Google and IBM have engaged with smart city and autonomous car projects.

In manufacturing and construction, the opportunities are equally significant. Rolling stock manufacturers (the companies that build trains) will need to adapt or partner to produce these new autonomous pods and equipment. This could mean retrofitting existing train designs with sensors and control systems, or designing brand-new vehicle platforms (like modular pods) from scratch. It’s a chance for innovation in an industry that often evolves slowly. We might see partnerships between traditional rail giants (Alstom, Siemens, CRRC, etc.) and tech firms or automotive companies to blend rail know-how with autonomous driving tech. At the same time, the infrastructure upgrades discussed earlier – new track connections, communication towers, electrification – spell lots of business for construction and engineering firms. Laying fibre optics along thousands of kilometres of track, installing advanced signalling equipment, building charging stations or energy storage at rail hubs: these projects will mobilise contractors and create jobs. Companies that specialise in electrification or in building intelligent transportation systems stand to gain contracts as rail networks invest in modernization.

The logistics and transport services sector will also evolve. New services and business models are likely to emerge once the infrastructure is in place. For example, we could see logistics providers offering “rail shuttle” services using autonomous pods, analogous to how courier companies use fleets of trucks. A distribution company might operate its own small fleet of autonomous rail vehicles, renting slots on the national network to send goods between its facilities on a flexible schedule. This blurs the line between rail operator and shipper – an Amazon or DHL, for instance, could effectively become a rail operator on an open-access automated network, using their own AI-driven pods to meet delivery commitments. That represents a new market dynamic and potentially new revenue streams for rail infrastructure owners (selling usage like a telecom network). On the passenger side, app-based on-demand rail travel could create businesses that function like Uber, but for autonomous train pods. Imagine a subscription service where commuters book a pod that picks them up and links into a train convoy for the bulk of the journey – tech and mobility companies might collaborate to offer such integrated services.

Energy and sustainability sectors have a stake as well. With increased rail electrification and power needs, there’s opportunity for renewable energy integration – perhaps dedicated solar farms powering certain routes, or energy storage systems that help balance loads when many pods need charging. Innovative energy start-ups could partner with railways to provide green power solutions or battery recycling programs for the large batteries the pods would use. Even the data generated by an AI rail network has value: analytics firms could spring up to help rail operators and users make sense of travel patterns, freight flows, and system performance, driving further efficiency improvements. In insurance and finance, new products will be needed to insure autonomous operations and to finance the acquisition of fleets of vehicles and infrastructure upgrades.

Crucially, this transformation could lower barriers to entry in the rail sector. Traditionally, running trains required huge capital and owning locomotives, cars, and hiring crews. In the future, a smaller company might lease a few autonomous pods and have software plan their routes – effectively “starting a railroad” in a digital sense. This could spur competition and innovation, much like deregulation did in telecom or aviation, but this time enabled by technology. Policymakers and investors should watch this space: those who move early to support or invest in these new paradigms stand to benefit as the industry grows. We are likely to see collaborative ventures too – partnerships between rail incumbents and nimble start-ups to pilot new systems, or consortiums forming to set standards (for instance, a group of freight companies might band together to ensure their pods and platforms are interoperable).

In summary, the shift to AI-driven rail is not just an upgrade of trains; it’s the birth of an entirely new rail-tech industry. From the drawing boards to the rail yards, countless enterprises will have a role to play. The next decades could witness the rise of companies that become as synonymous with smart rail transport as Boeing and Airbus are with aviation. For industry investors and innovators, it’s a time of grand opportunity – and for economies, it’s a chance to seize a leadership position in what could be one of the defining infrastructure projects of the 21st century.

A Transportation Renaissance

It’s rare that a single vision promises to tackle so many challenges at once: efficiency, sustainability, connectivity, and innovation. The concept of an AI-guided, hybrid rail network does just that. If realised, it could usher in a transportation renaissance, one that marries the reliability of rails with the flexibility of road travel, all while dramatically shrinking the carbon footprint of how we move. The journey won’t be without obstacles – technological bugs, cautious regulators, and public scepticism must all be overcome. But as we’ve seen in other industries, when the benefits are this clear, progress tends to win out.

Fast forward a couple of decades: autonomous electric pods zip along quiet tracks through the countryside, carrying goods and passengers at high speed. Highways are less clogged with heavy trucks, city air is cleaner, and logistics chains run with the synchronised efficiency of a finely tuned orchestra. A business can send its product across a continent overnight with minimal hassle; a family can travel to visit relatives in another city without a car, door-to-door via comfortable automated shuttles. Rail infrastructure – once seen as old-fashioned – becomes the smart backbone of national transport, integrated with ports, roads, and even air travel in a seamless intermodal web.

What’s especially encouraging is that elements of this future are already visible today. Driverless metros and mine trains have proven that automation can work in rail. AI systems are already helping human dispatchers make better decisions. And the pressures of climate change and traffic congestion are pushing society to innovate. Policymakers are increasingly viewing rail enhancements as strategic investments for sustainable growth. With continued collaboration between technologists, the rail industry, governments, and the public, the vision of independent, efficient AI-driven rail is not just a fanciful idea on paper – it’s a plausible destination on the horizon.

The coming years will likely bring a series of milestones: pilot programs, incremental deployments, and eventually full commercial services of autonomous trains and road-rail vehicles. Each success will build momentum and confidence. Importantly, this is not an exclusive high-tech dream for a few wealthy countries; the modular nature of these innovations means they can be adapted to different contexts, potentially benefiting developing regions with leapfrog transport solutions. In an optimistic scenario, the AI rail revolution helps drive economic development while also cutting emissions globally – truly a win-win outcome.

In the end, railroads have always been about connecting places and people, fuelling commerce and growth. In the 19th century they knitted nations together and accelerated the Industrial Revolution. In the 21st century, a reinvigorated, intelligent rail network could once again reshape economies and societies for the better. The tracks are laid, the technology is coming of age, and the will to change is gathering steam. All aboard – the future of transport is arriving, and it’s on track to be smarter, cleaner, and faster than ever.