Making Artificial Intelligence Work for Engineering Reality

Computational mechanics has long been one of the quiet workhorses of engineering and applied science. From structural analysis and geotechnical modelling to fluid dynamics and biomechanics, it underpins decisions that shape infrastructure, industry, and public safety. Traditionally, the field has leaned heavily on numerical methods such as the finite element method, finite volume techniques, and boundary element formulations. These approaches are mathematically rigorous and well understood, particularly for linear systems and problems with clearly defined boundary conditions.

However, the landscape has shifted. Modern engineering problems rarely arrive neatly packaged. Nonlinear material behaviour, tightly coupled multiphysics systems, and phenomena that span multiple spatial and temporal scales are now the norm rather than the exception. As these challenges accumulate, classical numerical solvers face growing computational costs and modelling complexity. Even with advances in high performance computing, many simulations remain slow, brittle, or impractical for real time decision making.

Against this backdrop, artificial intelligence has entered the conversation. Machine learning, neural networks, and data-driven surrogates promise dramatic speedups and new modelling flexibility. Yet enthusiasm has been tempered by legitimate concerns. Many AI models function as black boxes, rely on vast datasets that may not exist, and struggle when asked to extrapolate beyond their training regimes. For computational mechanics, where physical consistency and predictive reliability are non-negotiable, these limitations matter.

What is emerging instead is a more nuanced synthesis. Rather than pitting physics against data, researchers are increasingly focused on unifying them.

A Global Perspective on Physics Guided AI

In July 2025, researchers from Queensland University of Technology, Tsinghua University, and several international partner institutions published a perspective article in Acta Mechanica Sinica that directly addresses this crossroads. Their work offers a structured review of AI enhanced computational mechanics and, more importantly, proposes a roadmap for embedding physical laws deeply into data-driven learning frameworks.

The authors examine the current state of play with a critical eye. While acknowledging the transformative potential of AI, they argue that progress depends on moving away from purely empirical approaches. Instead, the future lies in physics- and data-guided artificial intelligence, where governing equations, conservation laws, and variational principles are integral to how models learn and operate.

This perspective is not framed as a wholesale replacement of established numerical methods. Rather, it positions AI as an amplifier of physical understanding, capable of accelerating computation while preserving interpretability and trust.

Three Dominant Paradigms in AI Enabled Mechanics

The study organises current research into three broad paradigms, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses.

Purely data-driven models are often the first port of call. Trained on simulation outputs or experimental measurements, these models can approximate complex mappings at remarkable speed. In many cases, they reduce hours of computation to milliseconds. That efficiency comes at a cost. Without explicit physical constraints, such models may violate conservation laws, produce non-physical results, or fail catastrophically when operating outside their training domain.

Physics-informed neural networks, commonly referred to as PINNs, attempt to close that gap. By embedding governing equations directly into the loss function, PINNs enforce physical consistency during training. This approach improves interpretability and reduces dependence on large datasets. Even so, practical challenges remain. PINNs often suffer from slow convergence, sensitivity to hyperparameters, and difficulty handling multiphysics coupling or long time horizons.

Neural operator learning represents a more recent development. Rather than learning a single solution, neural operators aim to learn mappings between entire function spaces. This allows a single model to generalise across families of boundary conditions or input parameters. While powerful, neural operators are typically data-hungry and may still drift away from physical fidelity when extrapolating.

Taken together, these paradigms illustrate both the promise and the limitations of current AI techniques in computational mechanics.

From Bottlenecks to Building Blocks

Rather than dwelling on shortcomings, the authors use these observations to define four forward-looking research directions. Each is designed to move AI enhanced mechanics away from black-box behaviour and towards foundational, physics-aware computation.

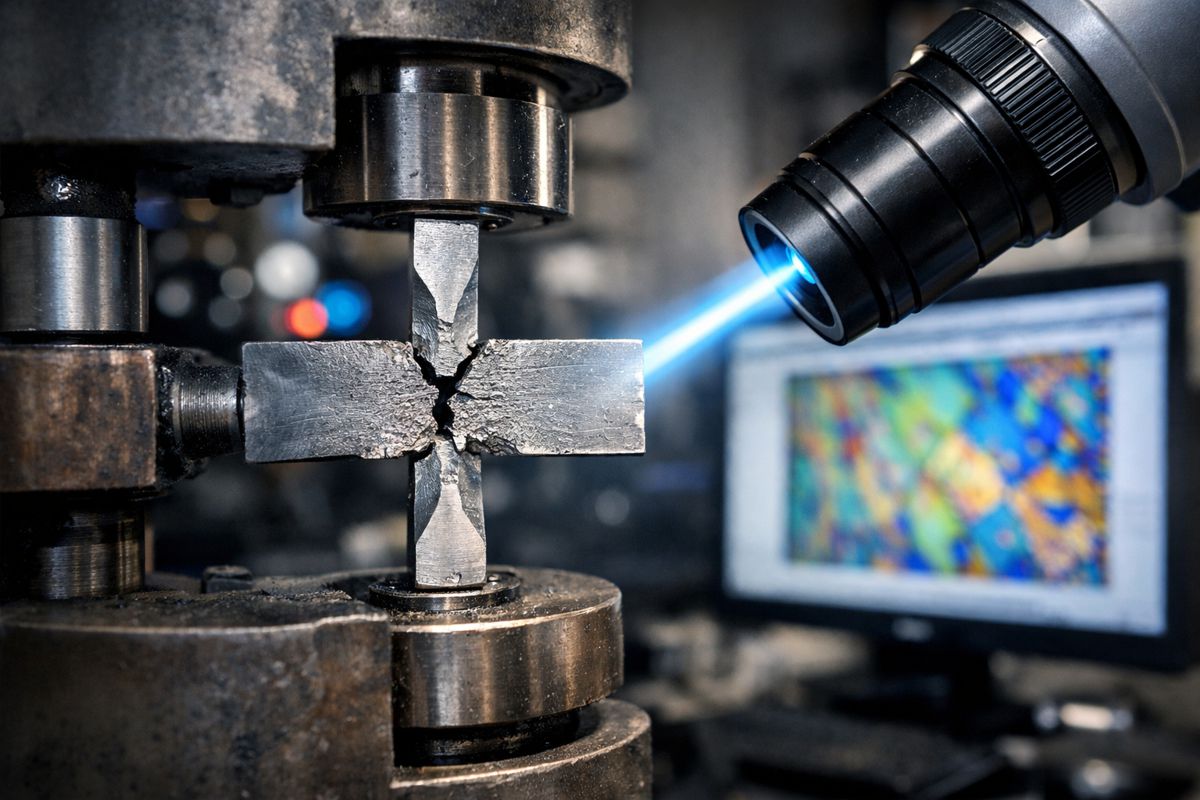

The first direction focuses on modular neural architectures. Inspired by traditional numerical solvers, these architectures reflect the underlying structure of physical problems. By aligning network components with physical processes, such as kinematics, constitutive laws, and equilibrium conditions, models gain stability and improved convergence. This modularity also makes them easier to interpret and adapt across applications.

A second avenue lies in physics-informed neural operators. By training directly on governing equations rather than on precomputed datasets alone, these models achieve resolution-invariant learning. In practical terms, this means a model trained on coarse representations can generalise to finer scales without retraining, a significant advantage for multiscale problems.

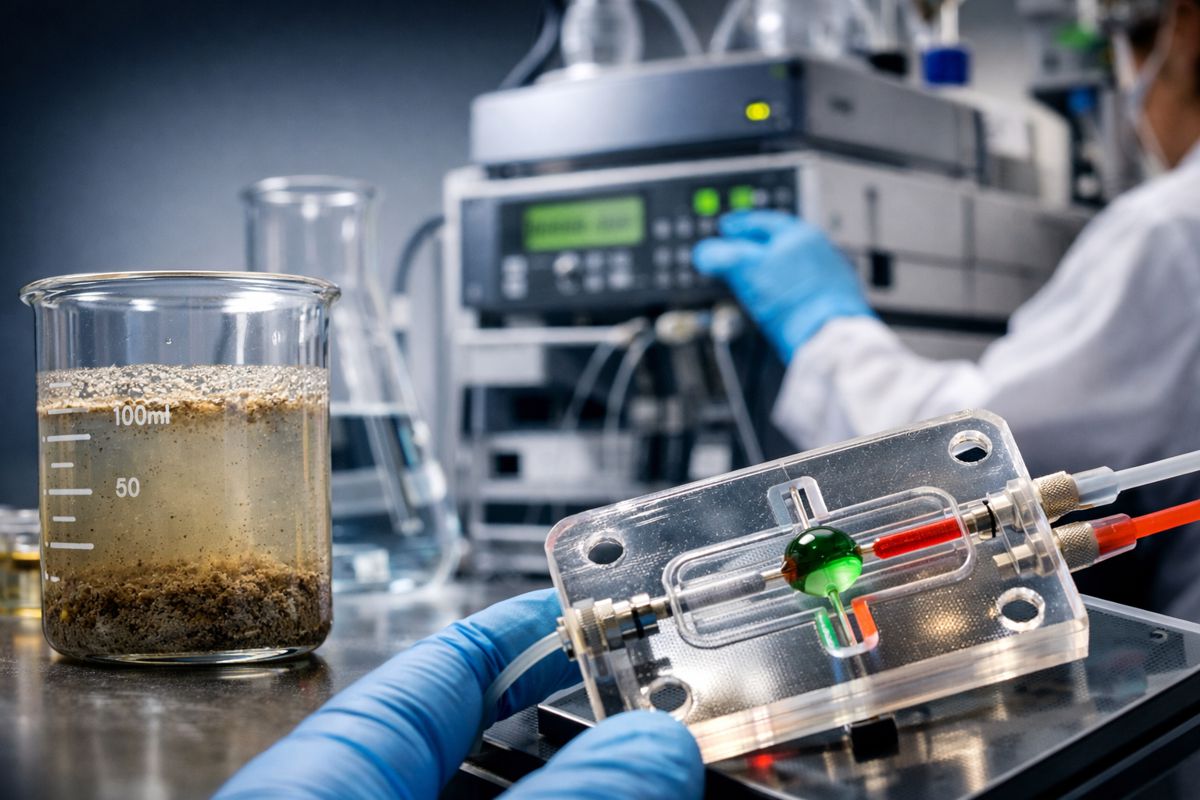

The third research direction targets multiphysics and multiscale systems, particularly in biomechanics. Biological systems rarely conform to neat separations of scale or discipline. Tissue mechanics, fluid transport, and biochemical signalling are deeply intertwined. Physics–data-integrated AI frameworks offer a way to unify these processes within a single computational framework, where classical methods often struggle.

Finally, the authors explore the combination of physical constraints with reinforcement learning. In structural optimisation and design, this pairing allows AI agents to explore unconventional solutions while remaining grounded in physical reality. The result is not random experimentation, but informed exploration within admissible design spaces.

Trust, Interpretability, and the Role of Physics

At the heart of the discussion lies a question of trust. Engineering decisions carry real world consequences, from structural safety to medical outcomes. Models that cannot explain themselves, or whose predictions cannot be traced back to physical principles, are difficult to deploy responsibly.

The authors are explicit on this point. As they note: “AI should not replace physical understanding, but rather amplify it.” This philosophy underpins the entire roadmap. By embedding conservation laws, symmetry principles, and variational formulations into learning architectures, physics-guided AI reduces uncertainty and improves robustness.

Such integration also supports better extrapolation. Models constrained by physics are less likely to produce implausible results when encountering unfamiliar conditions. For practitioners, this translates into greater confidence when applying AI tools beyond controlled laboratory settings.

Practical Implications Across Engineering and Science

The implications of physics- and data-guided AI extend well beyond academic interest. In engineering practice, faster and more reliable simulations can shorten design cycles, reduce costs, and support real time decision making. Nonlinear structures, multiphase flows, and advanced materials can be analysed with a level of efficiency previously out of reach.

In biomechanics, these methods open new possibilities for patient-specific modelling, surgical planning, and medical device design. Soft tissues, complex geometries, and evolving boundary conditions are all areas where traditional solvers face limitations.

There is also a strong link to digital twin technologies. Physics-aware AI provides a foundation for digital replicas that are not only responsive but physically grounded. Such twins can support predictive maintenance, system optimisation, and scenario testing across infrastructure and industrial assets.

Importantly, these advances do not discard decades of progress in computational mechanics. Instead, they build on that legacy, translating established theory into intelligent computational tools that are fit for contemporary challenges.

A Shift Towards Foundational Intelligent Computation

What emerges from the study is a clear shift in mindset. The future of computational mechanics is not purely numerical, nor purely data-driven. It sits at the intersection, where physical insight guides learning and data enhances efficiency.

By framing AI as a partner rather than a replacement, the authors offer a pragmatic and credible vision. One that recognises both the power of machine learning and the enduring value of physical laws.

As engineering systems continue to grow in complexity, this balanced approach may prove essential. Not just for faster computation, but for building models that engineers, regulators, and policymakers can trust.