Quantum Honeycomb Materials Move Closer To The Spin Liquid Frontier

The race to turn quantum theory into working technology isn’t being won by algorithms alone. It’s being shaped, just as decisively, by the physical materials capable of hosting quantum behaviour in the real world. In that sense, the latest research from the US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) lands squarely in the global spotlight, not because it promises an immediate leap in commercial quantum computing, but because it tackles one of the hardest missing pieces: creating stable, tuneable quantum materials that might actually behave the way advanced quantum models predict.

ORNL researchers have now synthesised and deeply characterised a magnetic compound known as potassium cobalt arsenate, engineered into a honeycomb-patterned lattice. The achievement is significant for condensed matter physics, but it also carries a longer-term relevance for industries that increasingly depend on next-generation computation, sensing, and secure communications. The honeycomb structure, in principle, can support a rare and highly sought state of matter called a quantum spin liquid, where magnetic spins don’t “lock” into a fixed pattern even at low temperature. That sort of restless quantum behaviour is exactly what researchers want if they are to develop new platforms for quantum technologies that are more resilient, controllable, and scalable.

There’s no overstating the challenge here. Quantum materials research has a habit of punishing shortcuts. What looks perfect on paper often turns stubborn or unstable in the laboratory, and even subtle distortions in crystal geometry can decide whether a material becomes the long-awaited quantum playground or just another well-behaved magnet. ORNL’s new honeycomb cobalt compound appears to sit near that boundary, hinting at spin-liquid potential while still displaying an ordered magnetic state. That’s not a disappointment; it’s the terrain researchers expected to have to cross.

Why Quantum Honeycomb Materials Matter Beyond the Laboratory

At a glance, a cobalt-based honeycomb crystal might feel distant from the immediate concerns of construction, infrastructure, and transport. But the global technology stack underpinning modern infrastructure is changing rapidly, and quantum research is no longer an isolated academic pursuit. Quantum computation, advanced materials, and ultra-sensitive measurement tools are all creeping into sectors that depend on optimisation, security, simulation and resilience.

In practical terms, quantum technologies could eventually strengthen grid design, accelerate materials discovery, enable new forms of secure communication, and drive more accurate modelling across energy and national security applications. These ambitions rely on hardware that can sustain quantum behaviour long enough to be useful. That is why quantum materials are so important. They are the bridge between theoretical models and deployable systems, and right now, that bridge is still under construction.

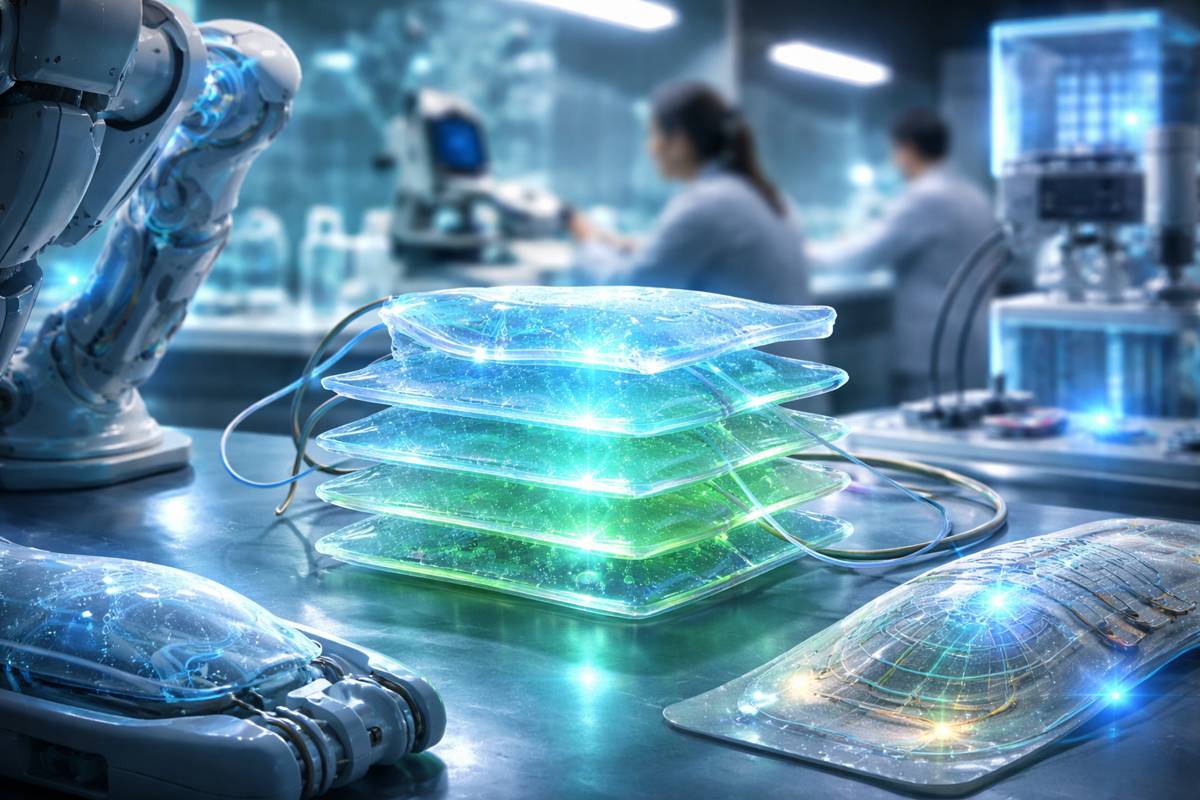

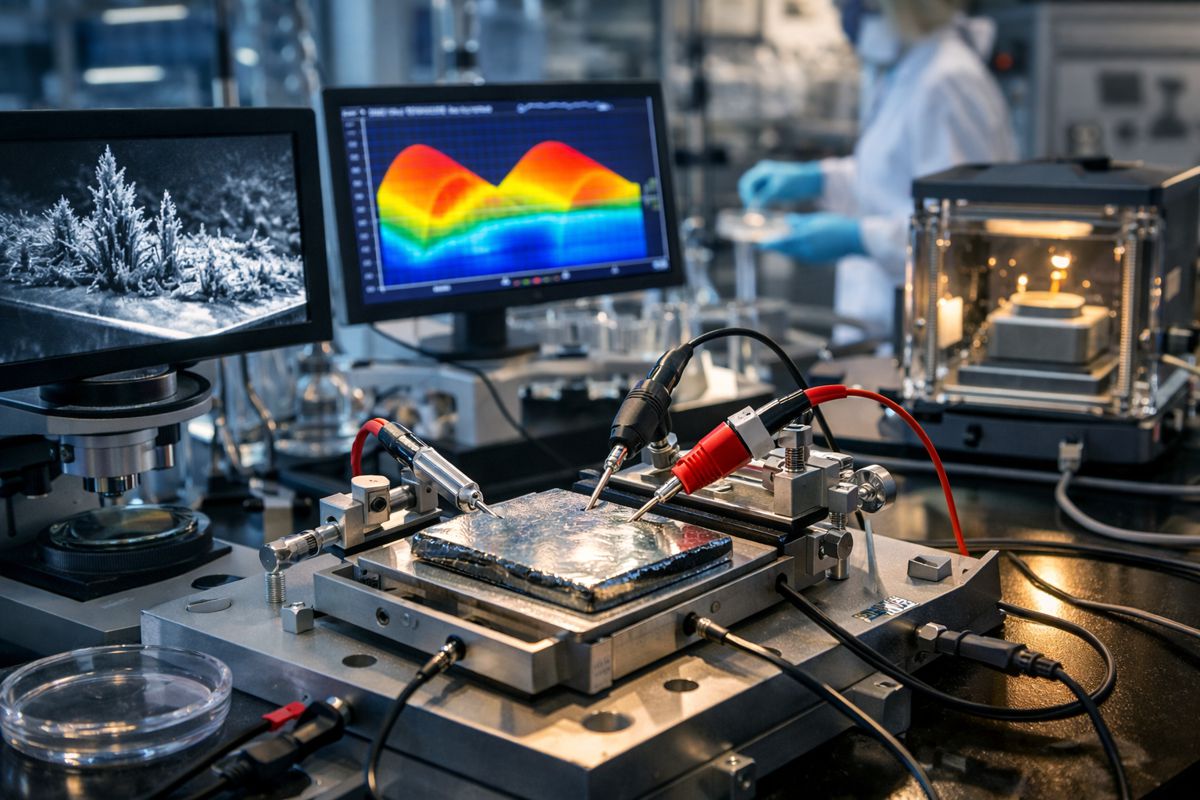

ORNL’s approach also reflects a broader trend shaping innovation across heavy industry: the integration of theory, experimentation, and computation into a single iterative pipeline. The old model of “make it and test it” has been replaced by a tighter loop where synthesis, neutron and electron characterisation, and computational prediction inform each other continuously. It’s a method that infrastructure technology firms will recognise instantly, because it mirrors the development of advanced composites, battery chemistry, and next-generation semiconductors. You could call it digital engineering for the quantum era.

The Quantum Spin Liquid Goal and the Hunt for Exotic Behaviour

A central objective of this research is the pursuit of a quantum spin liquid, a strange magnetic state where spins remain in a fluctuating, entangled condition rather than freezing into a conventional ordered pattern. Permanent magnets work because spins align and stay aligned. A spin liquid refuses to behave that way. Even when cooled, it keeps its quantum motion and interactions alive.

What makes this unusual state so prized is the possibility that it can host collective excitations with exotic properties. The ORNL team points to Majorana fermions, a type of emergent collective excitation that could become building blocks for future quantum technologies. In some theoretical frameworks, these excitations are appealing because they may be more resistant to certain types of interference from the environment, a long-running obstacle in real-world quantum devices.

This line of work traces back to a 2006 model proposed by Caltech physicist Alexei Kitaev, suggesting these excitations could form at the edge of a honeycomb crystal. The broader scientific community has been exploring candidate “Kitaev materials” ever since, including systems such as ruthenium chloride, sodium iridate, and barium cobalt arsenate. Many of these have insulating bulks paired with more conductive edge states, offering a promising architecture for hosting the kind of quantum excitations that advanced theories predict.

Still, good candidates are scarce. The ideal material needs to be structurally right, magnetically right, and stable enough to resist losing its quantum properties when it interacts with its environment. That combination is rare, and even the most promising materials have a habit of falling short in one crucial dimension.

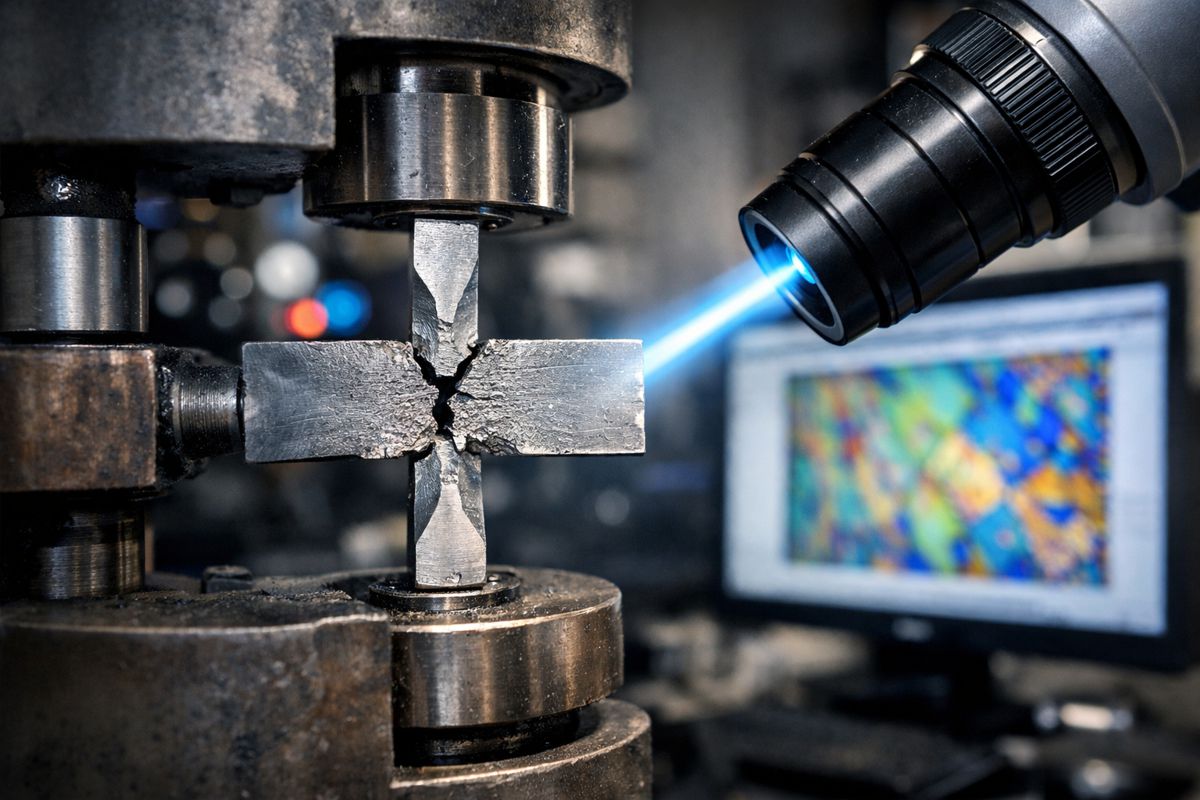

A Slight Distortion That Changes Everything

The ORNL team’s most detailed characterisation of potassium cobalt arsenate to date revealed a key fact: the honeycomb lattice is slightly distorted. That might sound like a footnote. In quantum materials, it’s more like a steering wheel.

The distortion changes how magnetic spins on cobalt atoms couple and align. Instead of floating in a quantum spin liquid regime, the compound displays strong coupling that pushes it toward an ordered magnetic state. That outcome matters because it suggests the material is close to the boundary researchers care about, but not quite over the threshold. In other words, it may be “tuneable”.

That’s the strategic value here. The material’s magnetic interactions might be adjusted by chemically modifying the compound, applying large magnetic fields, or potentially compressing it under high pressure. That opens up a pathway where a material that starts as an ordered magnet could be shifted toward the elusive spin liquid state through careful engineering.

As ORNL’s Craig Bridges, who led the study published in Inorganic Chemistry, put it: “This field is really tough, and quite young. Scientists are just beginning to understand how to observe and possibly manipulate Majorana fermions. We can’t claim seeing them yet in our honeycomb material, though we hope to eventually achieve that by modifying the material. We’re doing very basic research. It’s frontier work to try to find a material that will fit the predicted physics.”

There’s refreshing honesty in that statement. It’s not a promise of an imminent quantum revolution. It’s a reminder that foundational physics still has real frontiers, and the path to industrial-scale capability runs straight through them.

The Synthesis Breakthrough Behind Potassium Cobalt Arsenate

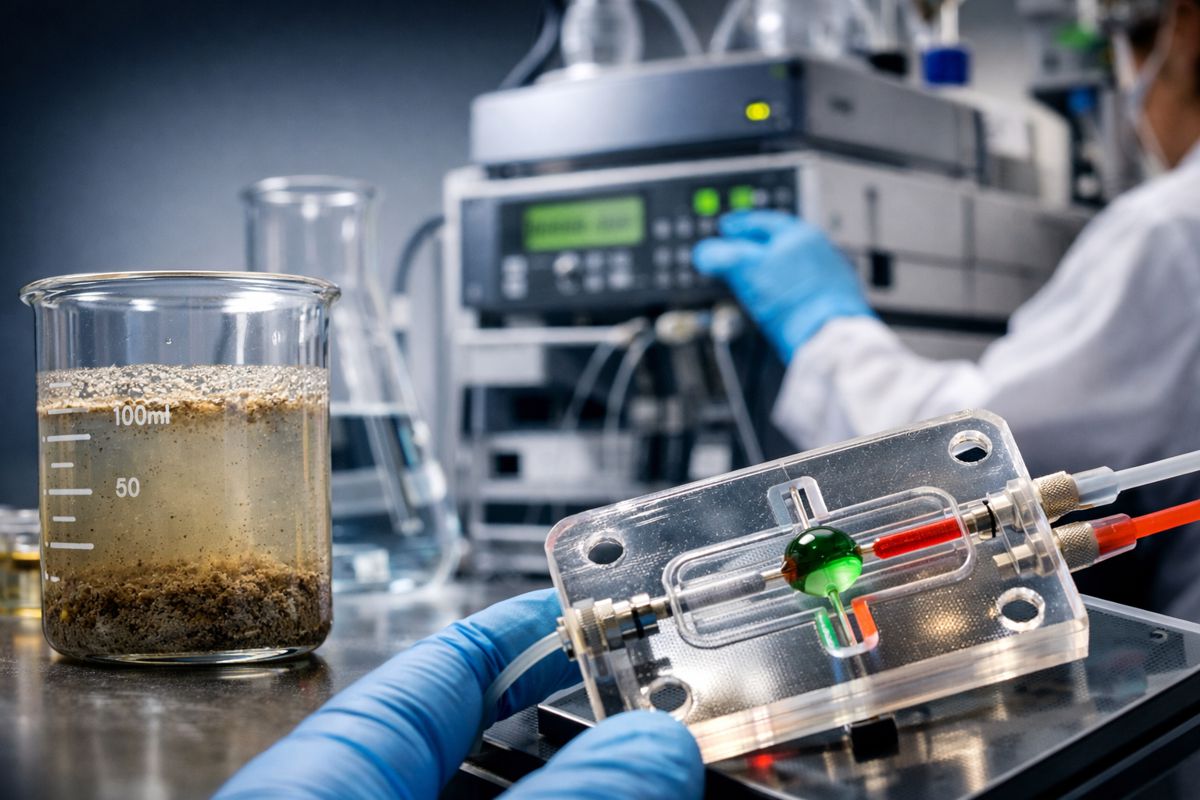

Getting to this point wasn’t quick. Bridges attempted to make the honeycomb material for many years, and the eventual success came through a synthesis approach that relied on careful control of temperature and chemical stability. The team heated a solution containing a compound of potassium, arsenic, oxygen and cobalt at low temperature, specifically to avoid decomposing the target structure, then crystallised the material out of solution.

This kind of synthetic precision is increasingly familiar across advanced engineering fields. Battery developers wrestle with electrolyte stability. Cement innovators juggle hydration chemistry and microstructure. Steelmakers refine heat treatments to tune crystalline phases. Quantum materials researchers are playing a similar game, except the target performance isn’t strength or durability. It’s quantum behaviour.

Following synthesis, the team verified chemical composition using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy. That work provided confidence that the material wasn’t simply “close enough”, but genuinely consistent with the intended chemical structure.

At a time when research credibility is increasingly tied to reproducibility and traceable characterisation, this step matters. If quantum materials are ever going to move from boutique experiments to consistent platforms, their synthesis routes must be robust, not artisanal.

Electron Microscopy and Neutron Scattering

Understanding a honeycomb quantum lattice isn’t something a single technique can accomplish. ORNL’s effort combined electron diffraction using transmission electron microscopy with neutron-based methods that are particularly powerful for studying magnetism.

Electron diffraction helped refine the understanding of crystal structure, while neutron scattering provided insight into magnetic behaviour. Neutrons interact strongly with magnetic spins, making them uniquely valuable in studying magnetic materials, particularly where spin interactions and ordering patterns are central to the story.

Using neutron scattering, ORNL scientists confirmed that their synthesis method exclusively produced crystals with the desired honeycomb lattice. That’s an essential validation because even slight contamination by unwanted crystal phases could compromise the interpretation of magnetic measurements and derail the entire effort.

ORNL’s Michael McGuire contributed heat capacity and magnetic measurements that revealed a transition where magnetic spins freeze into an ordered state. That transition indicates the material is near, but not in, a quantum spin liquid state. It behaves as a more conventional magnet, at least under the conditions tested so far, but its proximity to the boundary remains of deep interest.

This is where quantum materials research often becomes most valuable, not least because it provides a real object that can be adjusted. The difference between a “no” and a “not yet” can define a decade of progress.

Computational Insight Explains Why the Spin Liquid Hasn’t Emerged Yet

Even with careful synthesis and advanced measurement tools, the “why” behind magnetic behaviour often requires computation. ORNL’s theoreticians used the crystal structure information to calculate how cobalt spins are expected to interact with one another.

Those calculations revealed that the “Kitaev part” of the interaction is relatively weak compared to other more common interactions. That helps explain why the compound settles into an ordered magnetic state rather than a spin liquid.

It’s a crucial point because it shifts the story away from wishful thinking and toward engineering reality. If the key interaction is too weak, then the material won’t naturally sit in the desired quantum regime. However, if the balance of interactions can be tipped by changing chemical composition or applying high pressure, then the compound becomes a platform rather than a dead end.

Bridges emphasised this tuning approach without overselling it: “It’s unlikely that this material will provide an exact fit to the model. However, it could be a platform in which we could change the composition slightly to tune the material’s magnetism and achieve the physics that we need to realize a true quantum spin liquid.”

That phrase “platform” is doing a lot of work, and rightly so. In the technology world, platforms matter more than prototypes. A platform invites iteration, scaling, and the slow conversion of theory into capability.

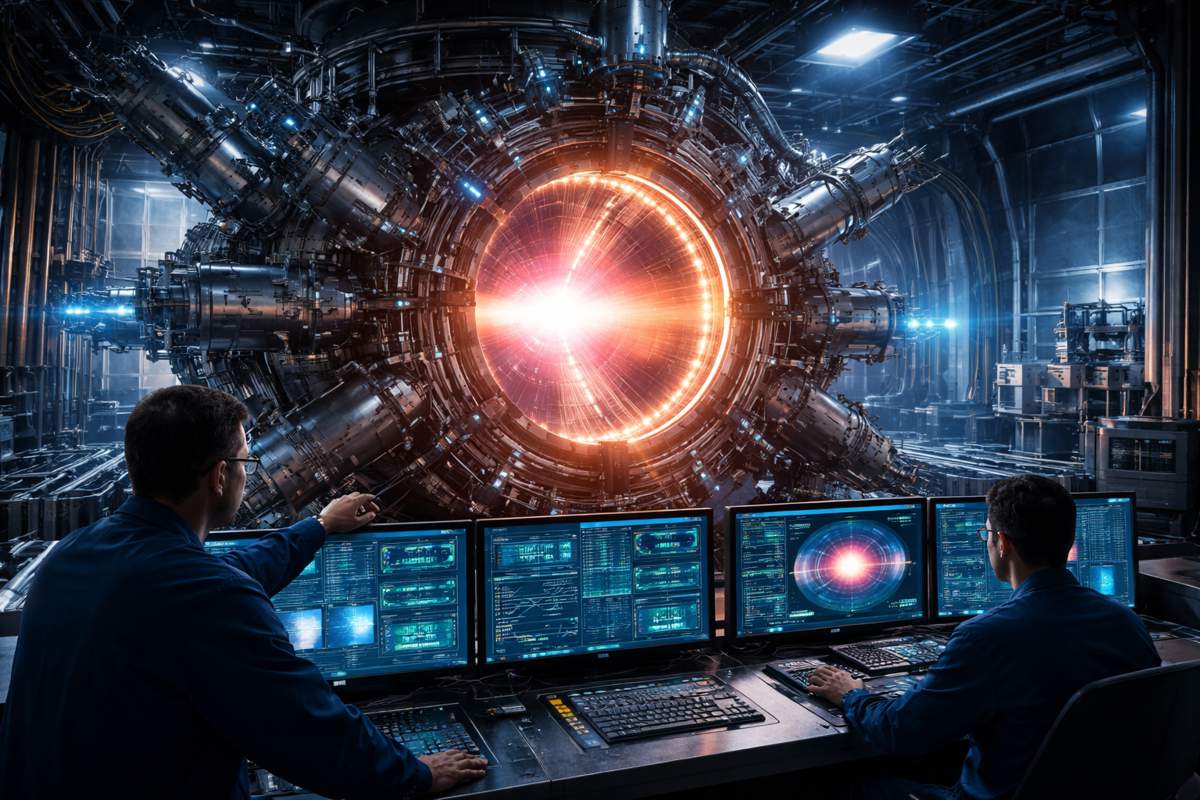

The Quantum Science Center and the Industrial Relevance of Basic Research

This work sits within a much larger ecosystem: the DOE’s Quantum Science Center (QSC), launched at ORNL in 2020, renewed in 2025, and led by QSC Director Travis Humble. The QSC includes 21 institutions spanning industry, academia and government, and it is one of five DOE National Quantum Information Science Research Centers.

That structure matters because quantum science is now too complex to be advanced by isolated teams. It demands cross-disciplinary collaboration where synthesis specialists, measurement scientists, and computational theorists work in concert. It also demands expensive national facilities, such as neutron sources and advanced microscopy centres, that few institutions can sustain independently.

The QSC’s work includes pioneering synthesis and characterisation of quantum spin systems, using advanced measurements such as neutron scattering. With its 2025 renewal, the centre began new efforts to simulate these same material properties using quantum computing methods tailored to the geometries and compositions of real materials.

In other words, the research isn’t only about making exotic crystals. It’s also about improving the tools for understanding them, including computational approaches that may themselves become part of the quantum technology toolchain.

There’s a parallel here with the industrial shift toward digital twins. Infrastructure and construction industries increasingly use simulation to model bridges, tunnels, road networks, and supply chains before building anything physical. Quantum researchers are now building the equivalent pipeline for quantum behaviour in matter, and that’s a foundational capability that could ripple outward over time.

From Exotic Physics to Future Infrastructure Technology

It would be easy, and inaccurate, to claim that potassium cobalt arsenate is a near-term technology for construction or transport. It isn’t. But it is part of a global movement that could reshape how the world builds and secures its critical systems.

Quantum technologies are being pursued because classical computing is approaching practical limits for certain tasks, especially those involving the simulation of complex quantum systems, optimisation problems at massive scale, and cryptography. Infrastructure investment, transport planning, power grid resilience, and defence logistics all sit in this computationally hungry category.

Materials like ORNL’s honeycomb cobalt compound matter because they may provide new ways to host and control exotic quantum excitations, potentially enabling more robust quantum devices. If Majorana-like excitations can be created and controlled reliably, they could become part of the hardware layer supporting future computation and sensing.

There’s also a broader lesson here for technology strategy. Breakthroughs don’t arrive fully formed. They arrive as awkward, imperfect platforms that require years of tuning. That’s how lithium-ion batteries evolved, how GPS became critical infrastructure, and how machine control systems turned into full autonomy stacks. Quantum materials research is following the same messy but productive path.

For now, ORNL’s potassium cobalt arsenate stands as a carefully built stepping stone. It proves a synthesis route. It confirms a honeycomb structure. It reveals a distortion that shapes magnetism. It provides a platform that might be tuned into something even more extraordinary.

And in the world of frontier science, that’s a very real kind of progress.