Lithium Metal Anodes Are Back at the Centre of the Energy Transition

The global push for higher-capacity, safer and longer-lasting batteries has reached a critical inflection point. Electric vehicles are scaling faster than anticipated, grid-scale energy storage is becoming a strategic asset rather than a pilot concept, and emerging sectors such as electric aviation and heavy-duty electrification are stretching the limits of existing lithium-ion technology. Now lithium metal has re-emerged as one of the most closely scrutinised materials in advanced battery research.

Lithium metal is not a newcomer. Its appeal lies in fundamentals that are hard to ignore. It offers an exceptionally high theoretical specific capacity and the lowest electrochemical potential among known anode materials. In simple terms, it promises lighter batteries with more energy packed into the same volume, a prize that could reshape everything from long-haul transport to renewable energy buffering. Yet for decades, those theoretical advantages have remained stubbornly out of reach in commercial systems.

The problem has never been energy density alone. Lithium metal anodes suffer from instability during repeated charging and discharging, leading to uneven lithium deposition, dendrite growth, the formation of electrically isolated dead lithium and the breakdown of interfacial layers. These issues undermine efficiency, shorten cycle life and, more critically, introduce serious safety risks. Fires and short circuits linked to uncontrolled lithium growth have long haunted the technology, relegating it to laboratories rather than production lines.

What has changed is not only the urgency of demand but the growing recognition that traditional, chemistry-only approaches are insufficient. A recent comprehensive review published in 2025 argues that lithium metal behaviour must be understood as a coupled electro-chemo-mechanical system. That shift in perspective has significant implications for how next-generation batteries are designed, tested and ultimately deployed across infrastructure-critical applications.

Moving Beyond Chemistry-Only Battery Design

For years, the dominant strategy for stabilising lithium metal focused on electrolyte formulation and electrochemical optimisation. Researchers sought better salts, additives and solvents to regulate lithium ion transport and suppress side reactions. While incremental gains were achieved, fundamental problems persisted. Dendrites still formed, interfaces still degraded and performance gains often came at the cost of manufacturability or operating constraints.

The latest research challenges the assumption that electrochemistry alone can solve these issues. Instead, it frames lithium plating and stripping as a dynamic process governed simultaneously by electrochemical reactions, mechanical stress and interfacial chemistry. These processes do not operate independently. They interact continuously during battery operation, with local changes in one domain influencing behaviour in the others.

At the heart of this framework is a simple but powerful observation. As lithium ions deposit onto a metal anode, they do not merely react and settle. They exert mechanical stress, deform surrounding structures and respond to pressure gradients at the interface. Over repeated cycles, these stresses accumulate, crack protective layers and redirect ion flux in ways that promote failure. Ignoring this mechanical dimension, the researchers argue, leaves battery designers blind to some of the most critical failure mechanisms.

By systematically analysing both liquid-state and solid-state battery systems, the review demonstrates how electro-chemo-mechanical coupling governs lithium morphology, reversibility and long-term stability. This approach replaces trial-and-error materials optimisation with a more predictive framework, one that aligns with how infrastructure-scale technologies are typically engineered.

How Lithium Actually Deposits and Grows

Lithium metal deposition is often discussed as if it were a simple plating process. In reality, it is a multi-stage phenomenon influenced by a wide range of operating and material parameters. The review traces this process from the earliest stages of ion desolvation and nucleation through to growth and eventual stripping during discharge.

Initial nucleation is highly sensitive to current density, overpotential, temperature and substrate properties. Under low overpotential and carefully controlled current densities, lithium tends to spread laterally across the surface, forming dense, moss-like structures. These morphologies are generally more reversible, allowing lithium to be stripped and redeposited with minimal loss during cycling.

Problems arise when operating conditions drift away from this narrow window. High overpotentials and aggressive charging rates encourage vertical lithium growth. Once protrusions form, they concentrate local electric fields, accelerating further deposition at their tips. The result is dendritic growth that can pierce separators or solid electrolytes, creating internal short circuits.

Mechanical factors play a decisive role here. As lithium deposits unevenly, stress builds at the interface. Localised pressure alters ion transport pathways, effectively steering lithium ions toward already stressed regions. Over time, this feedback loop amplifies instability, even in systems with chemically optimised electrolytes.

The Solid Electrolyte Interphase as a Mechanical Structure

Few components in battery science are as widely discussed or as poorly understood as the solid electrolyte interphase. Often treated primarily as a chemical passivation layer, the SEI is now being re-evaluated as a mechanical structure with its own failure modes.

An effective SEI must strike a delicate balance. It needs high lithium-ion conductivity to allow efficient cycling, while maintaining low electronic conductivity to prevent parasitic reactions. At the same time, it must be mechanically robust and structurally uniform. If it cracks, fresh lithium is exposed, triggering renewed side reactions and accelerating degradation.

The review highlights how heterogeneous or fragile SEI layers fail under repeated mechanical stress. Expansion and contraction during cycling generate microcracks, which act as entry points for electrolyte attack. In contrast, mechanically stable SEIs can distribute stress more evenly, suppressing dendrite initiation and extending cycle life.

This insight reframes SEI engineering as a structural challenge as much as a chemical one. Materials selection, layer thickness and elastic properties become just as important as chemical composition. For large-format batteries used in vehicles or grid storage, where mechanical loads and thermal gradients are unavoidable, this perspective is particularly relevant.

Why Solid-State Batteries Are Not Immune

Solid-state batteries are often presented as the definitive solution to lithium metal instability. By replacing flammable liquid electrolytes with solid materials, they promise improved safety and higher energy density. However, the review makes clear that solid-state systems introduce their own electro-chemo-mechanical challenges.

The interface between lithium metal and solid electrolytes is especially vulnerable to mechanical mismatch. Differences in stiffness, thermal expansion and deformation behaviour lead to stress concentrations during cycling. These stresses can cause void formation at the interface, reduce contact area and create pathways for lithium filament penetration.

Crucially, the research shows that neither high mechanical stiffness nor chemical stability alone is sufficient. A rigid electrolyte may resist deformation but crack under stress, while a softer material may accommodate strain but fail to block dendrite growth. Effective design requires a holistic view of stress evolution, defect distribution and ion transport pathways.

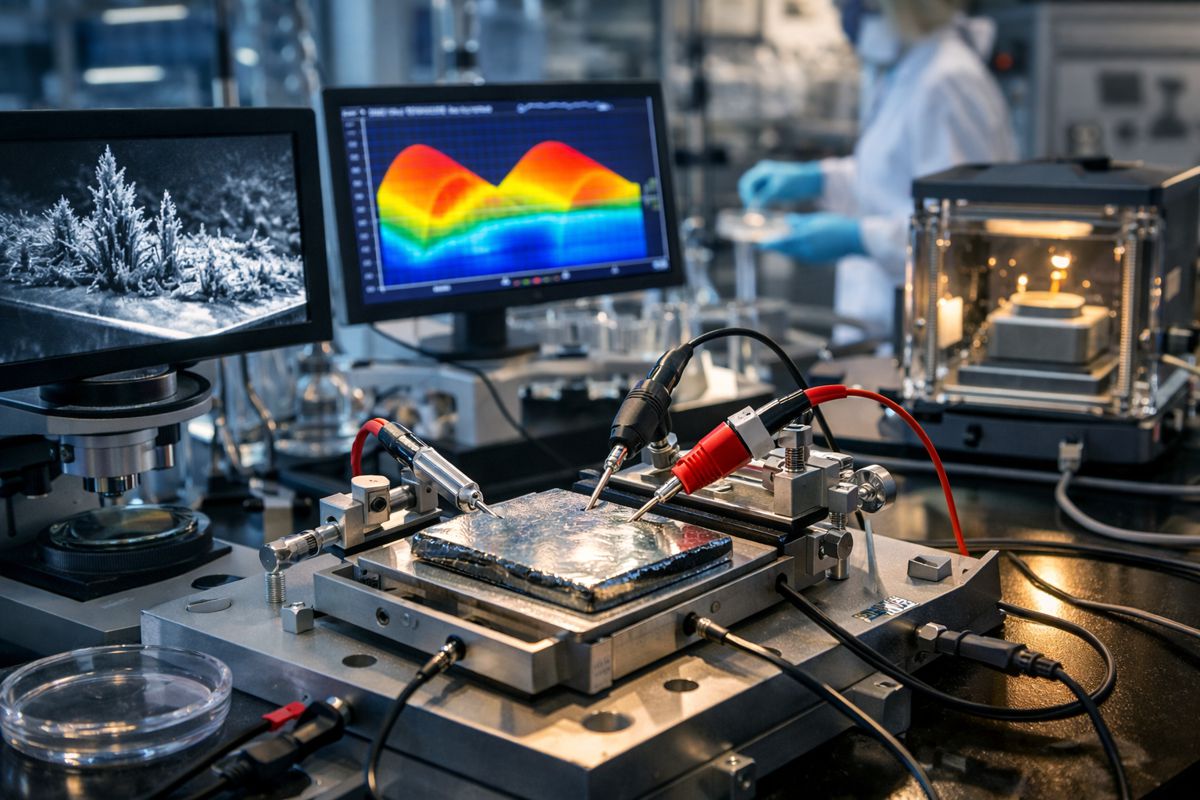

Advanced imaging techniques and multiphysics modelling are identified as essential tools for understanding these interactions. By visualising lithium growth in real time and simulating coupled electro-chemo-mechanical behaviour, researchers can move toward predictive control rather than reactive mitigation.

A Multiphysics Perspective on Battery Failure

One of the most significant contributions of the review is its emphasis on lithium metal behaviour as an inherently multiphysics phenomenon. Local stress concentrations do not merely accompany electrochemical reactions; they actively influence where and how those reactions occur.

As the authors state: “The behaviour of lithium metal cannot be understood through electrochemistry alone.” They further note: “Mechanical stress, interfacial chemistry, and ion transport are inseparably linked during battery operation.” These statements encapsulate a shift that mirrors developments in other infrastructure sectors, from geotechnical engineering to materials science, where coupled processes are now standard considerations.

This perspective has practical implications. It suggests that battery failure is often triggered not by a single flaw but by the interaction of multiple, reinforcing mechanisms. Addressing one parameter in isolation may delay failure but rarely prevents it. Integrated design strategies are therefore essential for scaling lithium metal technologies beyond laboratory cells.

Implications for Infrastructure-Scale Energy Storage

For policymakers and investors, the significance of this research lies in its potential to accelerate commercial readiness. Lithium metal batteries are widely seen as a cornerstone technology for next-generation energy systems, particularly where weight, volume and efficiency constraints are critical.

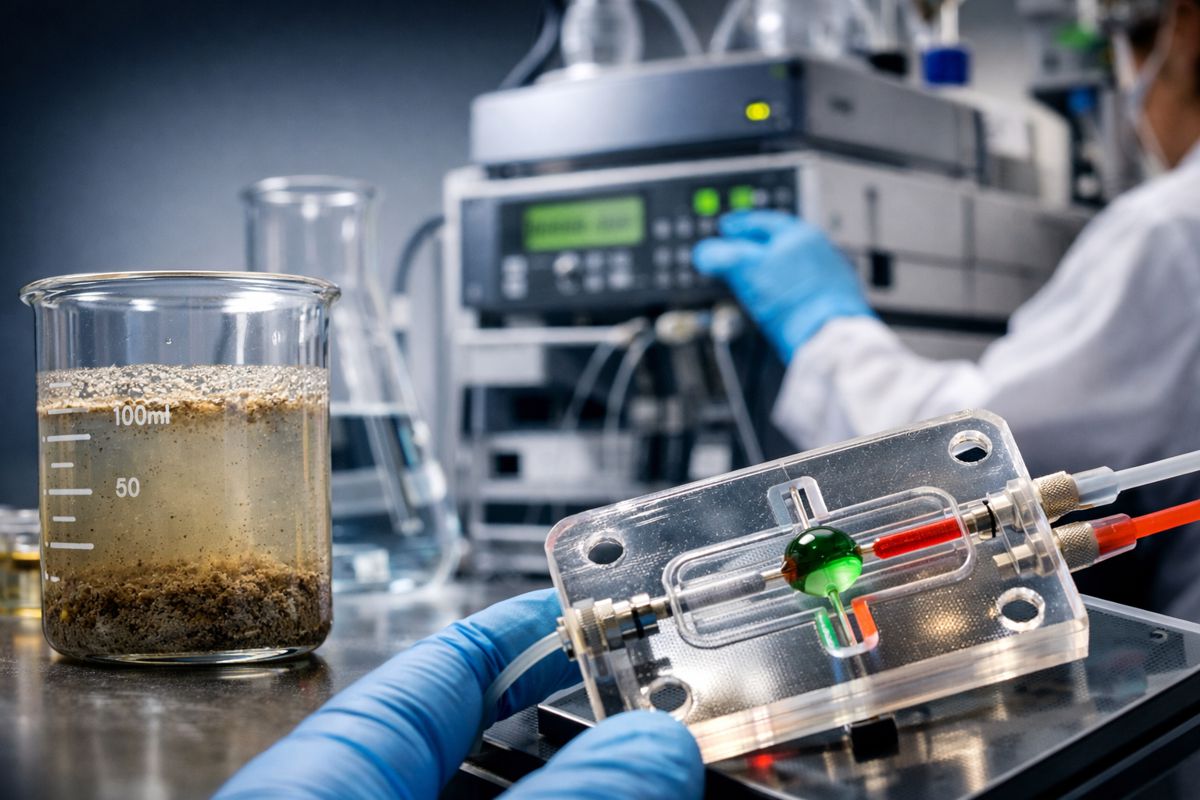

The electro-chemo-mechanical framework outlined in the review supports a range of practical strategies. These include stress-engineered interfaces that distribute mechanical loads more evenly, mechanically optimised SEI layers that resist cracking, pressure-controlled cycling protocols and electrolyte formulations tailored to regulate both ion transport and stress distribution.

Such approaches are especially relevant for solid-state batteries, where safety and longevity remain the primary barriers to adoption. Beyond vehicles, the implications extend to grid-scale storage, offshore renewable integration and high-reliability systems used in aviation and defence infrastructure.

More broadly, the framework offers a roadmap for transitioning lithium metal batteries from experimental prototypes to dependable industrial products. By aligning battery design with the principles of multiphysics engineering, the sector moves closer to the predictability and robustness expected of critical infrastructure technologies.

Toward Predictable and Scalable Lithium Metal Systems

The renewed focus on lithium metal anodes reflects both necessity and opportunity. As energy systems become more electrified and decentralised, the demand for high-performance storage will only intensify. Incremental improvements to existing lithium-ion technologies may no longer be sufficient.

By clarifying the fundamental mechanisms behind lithium metal instability, this research provides a foundation for more rational design strategies. It encourages the industry to move beyond isolated fixes and toward integrated solutions that acknowledge the complex reality of battery operation.

In doing so, it also bridges a gap between materials science and infrastructure engineering. Batteries are no longer just electrochemical devices; they are mechanical systems operating under stress, pressure and thermal load. Recognising and designing for that reality may prove decisive in unlocking the full potential of lithium metal for the global energy transition.