Building the Construction Control Tower

Across construction, transport, mining and energy, the phrase “control tower” has quietly changed meaning. It no longer refers to a room full of screens or a sophisticated reporting dashboard. Increasingly, it describes an operating model: a way of running complex portfolios where decisions are made earlier, with better context, and with a clearer understanding of consequence.

Anyone who has spent time around major capital programmes will recognise the problem control towers are trying to solve. Information is plentiful, but insight is scarce. Projects generate data at speed, yet portfolio leaders still struggle to answer basic questions about risk, sequencing, resilience and exposure. By the time issues surface in formal reporting, options have narrowed and costs have hardened. Control tower thinking has emerged not because the industry wanted another layer of technology, but because traditional governance structures were no longer keeping up with the scale and interdependence of modern infrastructure delivery.

Control Towers in Construction

The timing is not accidental. Construction portfolios are larger, more interconnected and more politically visible than at any point in recent memory. Infrastructure owners are juggling cost inflation, labour constraints, supply chain fragility, decarbonisation pressures and heightened regulatory scrutiny, often at the same time. Projects that once stood alone now sit within tightly coupled programmes, where a delay in one location ripples across suppliers, funding profiles and public confidence.

In that environment, the limits of project-centric management become obvious. Optimising individual projects in isolation can actively undermine portfolio outcomes. Control towers respond to this reality by shifting the centre of gravity upwards. Instead of asking whether a single project is on track, they focus on whether the portfolio as a whole is drifting towards unacceptable risk, and what can be done about it while there is still room to manoeuvre.

Borrowing From Aviation, Logistics and Defence

The intellectual roots of the control tower lie outside construction. Aviation offers the clearest parallel. Air traffic control exists to manage a complex, dynamic system where visibility, authority and timing are inseparable. Decisions are taken continuously, based on a shared operational picture, with clearly defined escalation and intervention rights. The system does not wait for monthly reports.

Logistics adapted the same principles to supply chains. As global networks grew more exposed to disruption, companies built control towers to gain end-to-end visibility across suppliers, ports, warehouses and transport corridors. Over time, these evolved from static dashboards into coordination hubs, designed to prioritise issues, manage exceptions and orchestrate responses across multiple parties.

Defence thinking adds an important cautionary note. Military doctrine around the common operational picture consistently stresses that visibility without prioritisation can be worse than useless. Flooding decision-makers with unfiltered information slows response and obscures what matters. The lesson for construction is uncomfortable but necessary: control towers succeed or fail on governance and discipline, not on the number of screens they deploy.

From Dashboards to Decision Engines

Early construction control towers looked much like their supply chain counterparts a decade ago. They aggregated schedules, cost reports and progress metrics into central views. These systems improved transparency, but they rarely changed outcomes. They explained what had already happened rather than shaping what happened next.

The more mature examples now being deployed take a different approach. They are built explicitly to support decisions, not just reporting. Data is structured around questions leaders actually need to answer: where risk is accumulating, which constraints are binding, and what trade-offs are available. Scenario analysis, forecasting and exception management are prioritised over retrospective status updates.

This shift matters because it changes behaviour. When a control tower is designed as a decision engine, it forces clarity about who decides what, on what basis, and within what timeframe. That clarity is often missing from traditional programme governance, where accountability diffuses across layers of committees and assurance processes.

The Move From Projects to Networks

One of the most significant implications of control tower thinking is the move from project-centric to network-centric oversight. Modern infrastructure behaves less like a collection of discrete builds and more like an ecosystem. Projects share suppliers, labour pools, access constraints, regulatory interfaces and political attention.

Control towers are designed to surface those interdependencies. By treating projects as nodes within a wider network, they make it possible to see how local issues propagate. A procurement delay on one contract may tighten capacity elsewhere. A design change in one location may cascade through manufacturing schedules across an entire programme.

For asset owners, this perspective supports more deliberate sequencing and investment decisions. Rather than reacting to problems as they arise, portfolios can be shaped to reduce systemic exposure, even if that means accepting short-term inefficiencies on individual projects.

Portfolio-Level Intelligence in Practice

At portfolio level, the value of a control tower lies in its ability to frame trade-offs explicitly. Leaders can compare risks across projects, understand where intervention will have the greatest effect, and allocate contingency with intent rather than instinct.

This is particularly important in the public sector, where decisions are scrutinised long after they are taken. Portfolio construction intelligence provides an evidential basis for prioritisation, helping owners explain why resources were shifted, why certain projects were slowed or accelerated, and how risks were managed collectively rather than piecemeal.

Crucially, portfolio intelligence is not about achieving perfect foresight. It is about reducing blind spots. By shortening the distance between emerging signals and senior decision-makers, control towers create time, and in capital programmes, time is often the most valuable currency available.

Seeing Risk Across Programmes

Risk management is where control towers most clearly depart from traditional practice. On many programmes, risks are still logged, scored and mitigated at project level, then summarised upwards. Patterns only become visible when it is too late to respond cheaply.

Control towers invert that logic. They aggregate risk signals across projects, allowing trends to be identified early. Repeated safety incidents, productivity dips or inspection delays can be analysed collectively, revealing systemic issues rather than isolated failures.

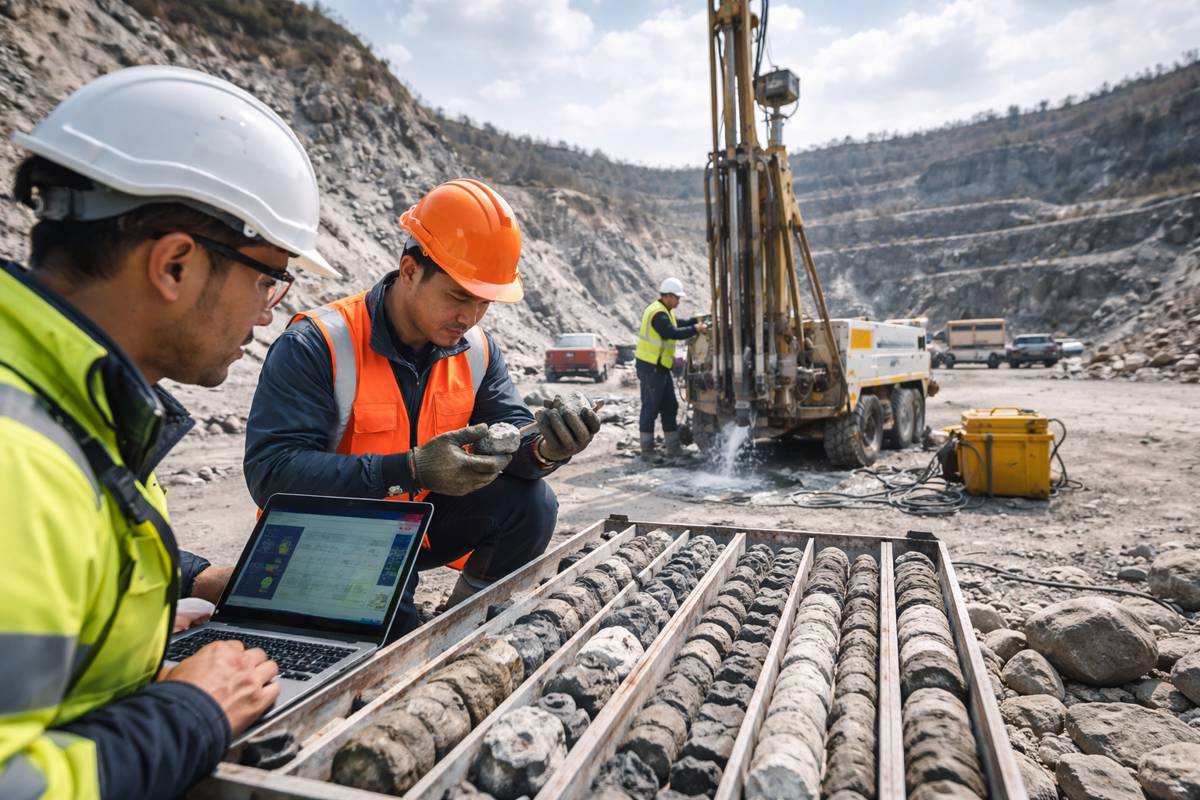

This approach has proved particularly valuable in sectors such as mining and transport, where similar activities are repeated across multiple sites. Lessons learned in one location can be applied elsewhere before problems recur. Over time, this builds a more resilient operating model, grounded in evidence rather than post hoc explanation.

Integrating BIM, IoT and Delivery Data

Technically, control towers depend on integration. Building information models, scheduling systems, cost controls, sensor data and safety platforms all feed into a common environment. When integration works, leaders gain a live picture of how physical progress, commercial exposure and operational risk interact.

In practice, this integration is as much organisational as technical. Data standards, classification systems and workflows must align across contracts and suppliers. Information needs to be timely, trusted and traceable. Without that discipline, analytics quickly lose credibility.

The emergence of common data environment standards has made this integration more feasible. They provide a structured backbone for information exchange, reducing friction between design, construction and asset management. Control towers build on that foundation, using it to connect information flows directly to decision-making routines.

Digital Twins and the Control Tower

Digital twins are often cited as a cornerstone of control tower capability, but their value depends on how they are used. Static visualisations add limited insight. What matters is the ability to link models to live data and management processes.

When digital twins are embedded into a control tower, they become tools for testing scenarios and understanding consequences. Leaders can explore how schedule changes affect access, how design adjustments influence maintenance strategies, or how operational constraints shape construction sequencing.

This integration shifts digital twins from being design artefacts to becoming management assets. It also exposes uncomfortable truths. Models that are poorly structured or disconnected from reality quickly lose relevance when they are placed under operational pressure.

Lessons From Mining and Transport

Mining offers some of the clearest parallels for construction. Remote operations centres have been used for years to coordinate mines, processing facilities, rail systems and ports from single locations. Their success has hinged less on technology than on operating discipline.

Experience from these environments consistently points to the same conclusion. The real transformation comes from new ways of working: standardised processes, clear decision rights and continuous learning. Screens and analytics support that shift, but they do not create it.

Transport operations tell a similar story. Road and rail networks have long relied on central operations centres to manage incidents, coordinate maintenance and communicate with users. These centres work because authority is clear and response is immediate. Extending that model into construction delivery is a logical, if challenging, next step.

The Human Layer

Despite the emphasis on data and technology, control towers are fundamentally human systems. They concentrate responsibility, and with it, accountability. Someone has to decide what constitutes a material issue, when to intervene, and how to balance competing priorities.

This creates new demands on skills and roles. Control tower teams typically combine project controls expertise with operational awareness and commercial judgement. They act as interpreters, translating signals into actions that delivery teams can execute.

Without clear governance, control towers quickly stall. If escalation routes are ambiguous or authority is contested, insights accumulate without effect. Successful implementations are explicit about decision rights and unapologetic about exercising them.

Integration, Trust and Cyber Risk

Integration brings risk as well as reward. Control towers concentrate data and connectivity, making them attractive targets for cyber attack. As they begin to touch operational technology, the stakes rise further.

Owners need to treat cybersecurity as a core design requirement, not an afterthought. Segmentation, access control and resilience planning are essential, particularly where control towers interface with live assets. Regulation is moving in this direction, and expectations are rising accordingly.

Trust is equally critical. If delivery teams doubt the accuracy or intent of control tower insights, they will work around them. Building trust requires transparency about data sources, assumptions and limitations, as well as a willingness to acknowledge uncertainty.

What Comes Next

The future of the construction control tower is unlikely to be a single monolithic system. More plausibly, it will operate as a portfolio layer, sitting above existing tools and drawing in the signals that matter most.

As connectivity improves and remote operations expand, the boundary between construction and operation will continue to blur. Control towers will increasingly support whole-life decision-making, linking delivery choices to long-term asset performance.

For asset owners, operators and governments, the implication is clear. Control towers are not about control for its own sake. They are about shortening the distance between reality and decision. In an industry defined by long timelines and high consequence, that capability is becoming a prerequisite for credible leadership.