Hyperspectral Imaging Is Transforming How Cities Understand Infrastructure

Across the developed world, transport authorities face a familiar dilemma. Roads are deteriorating faster than maintenance budgets can keep pace, yet inspection methods remain largely unchanged. The United States alone faces roughly $1.1 trillion in highway and bridge investment needs over the next two decades, according to the Federal Highway Administration. Meanwhile the American Society of Civil Engineers reports that nearly 39 percent of major roads remain in poor or mediocre condition.

Those numbers reflect a wider global pattern rather than a local anomaly. Urbanisation, heavier vehicles, climate extremes and utility works constantly disturb pavement structures. Every resurfacing layer, sealant treatment and patch repair creates a hidden history beneath the tyres of passing traffic. Yet engineers still rely heavily on visual inspections, limited sampling and paperwork records that may be incomplete or outdated.

Recent research led by Jessica Salcido and Professor Debra Laefer at New York University suggests that cities may soon read that history directly from the road surface itself. Using airborne hyperspectral imagery captured by the ITRES microCASI-1920 VNIR sensor, their studies demonstrate that pavement composition, ageing and repair patterns can be detected remotely and objectively. In practical terms, light reflected from asphalt may now reveal more than maintenance archives ever could.

Seeing Materials Beyond Human Vision

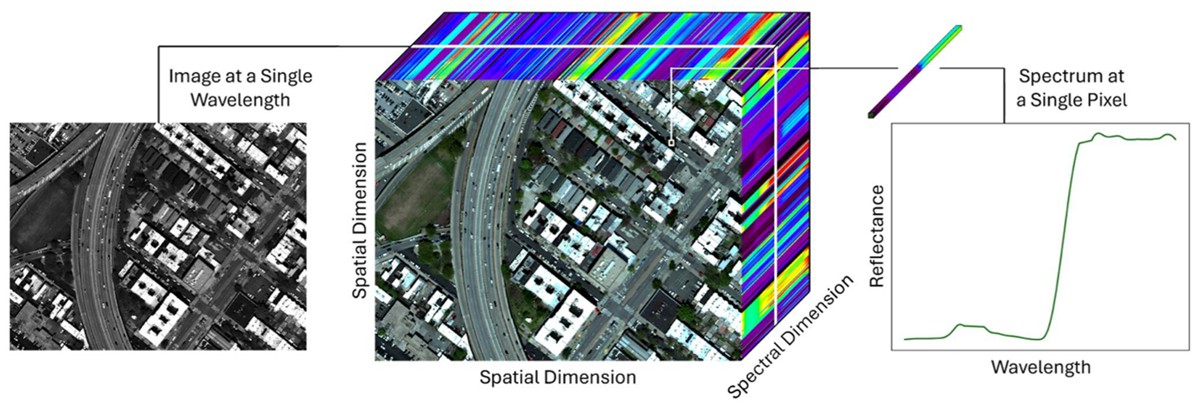

Traditional photography captures three colour bands: red, green and blue. Hyperspectral imaging operates on a different scale entirely. Instead of broad colour channels, sensors measure reflectance across hundreds of narrow wavelength intervals, extending beyond the visible spectrum into regions human vision cannot perceive.

Every material interacts with light differently. Asphalt oxidises over time, concrete cures and changes chemistry, coatings fade, moisture alters reflectance, and pollutants modify surface composition. These processes leave spectral fingerprints. Hyperspectral sensors measure those fingerprints and translate them into identifiable patterns.

In effect, a road surface becomes readable data. A patch repair laid months earlier reflects light differently from adjacent pavement poured years before. Even traffic loading leaves signatures, as heavy vehicles polish aggregate differently across lanes.

For infrastructure managers, that matters enormously. Current inspection regimes depend on human judgement and periodic surveys. Hyperspectral imaging instead offers repeatable measurement at city scale. Roads, roofs and bridges can be monitored objectively rather than interpreted subjectively.

The Missing Urban Materials Dictionary

Yet the research uncovered an unexpected obstacle. Hyperspectral identification depends on reference libraries. A sensor can only recognise a material if its spectral signature is already documented and verified.

Salcido and Laefer examined publicly available spectral databases and discovered a striking imbalance. Out of 476,592 accessible spectral signatures worldwide, only 0.61 percent represented urban materials. Most entries focused on vegetation, soils and minerals, reflecting the historical roots of remote sensing in environmental science.

Even within that small subset, critical metadata was often missing. Entries frequently lacked information such as:

- Material age

- Manufacturing process

- Surface coatings

- Moisture content

- Environmental exposure

- Viewing geometry

Without that context, two visually identical asphalt samples could appear spectrally different for reasons unrelated to deterioration. Conversely, different materials might appear similar under certain conditions. For engineers seeking actionable intelligence, incomplete references undermine reliability.

Urban materials complicate the challenge further. Asphalt oxidises, binder chemistry evolves, pollution deposits accumulate, and weather cycles alter surface texture. The spectral identity of a road is not static. It evolves continuously.

To address this gap, the researchers proposed a 14 element metadata framework specifically designed for built infrastructure. The concept is straightforward but powerful: create a standardised “dictionary” describing materials not only by spectrum but by physical and environmental context. Once established, hyperspectral readings could be compared reliably across cities and climates.

Mapping Pavement Age from the Air

While one study highlighted missing data, the second demonstrated what becomes possible when high quality imagery and rigorous classification methods are applied together.

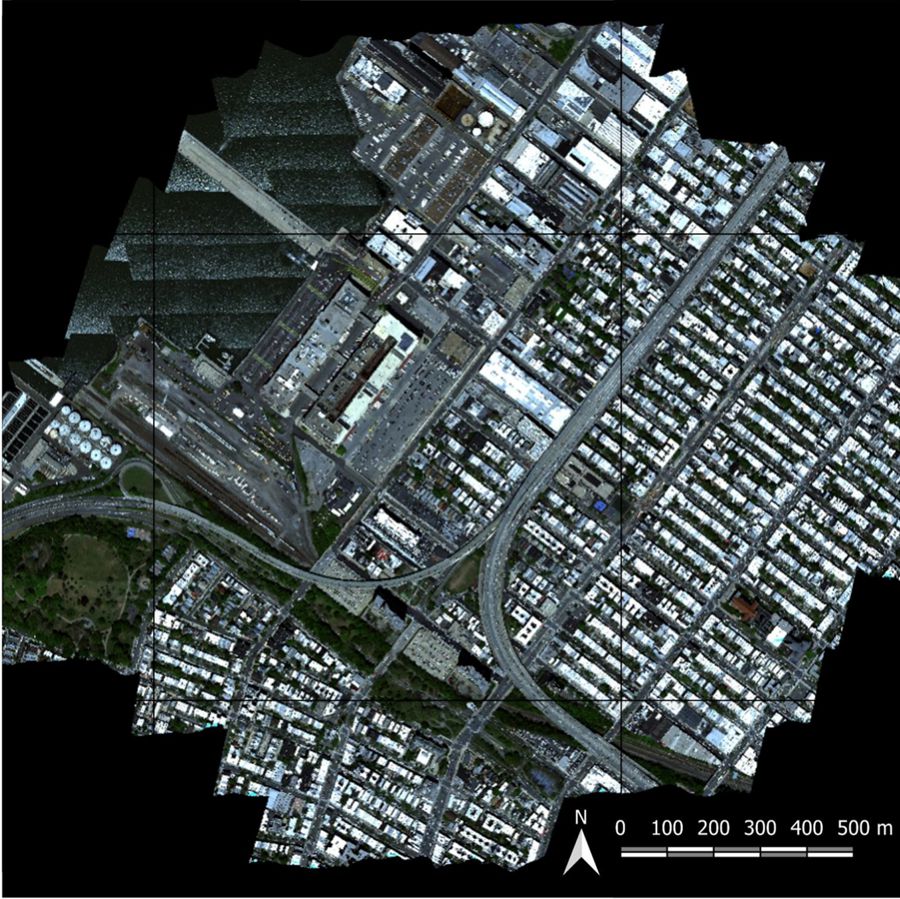

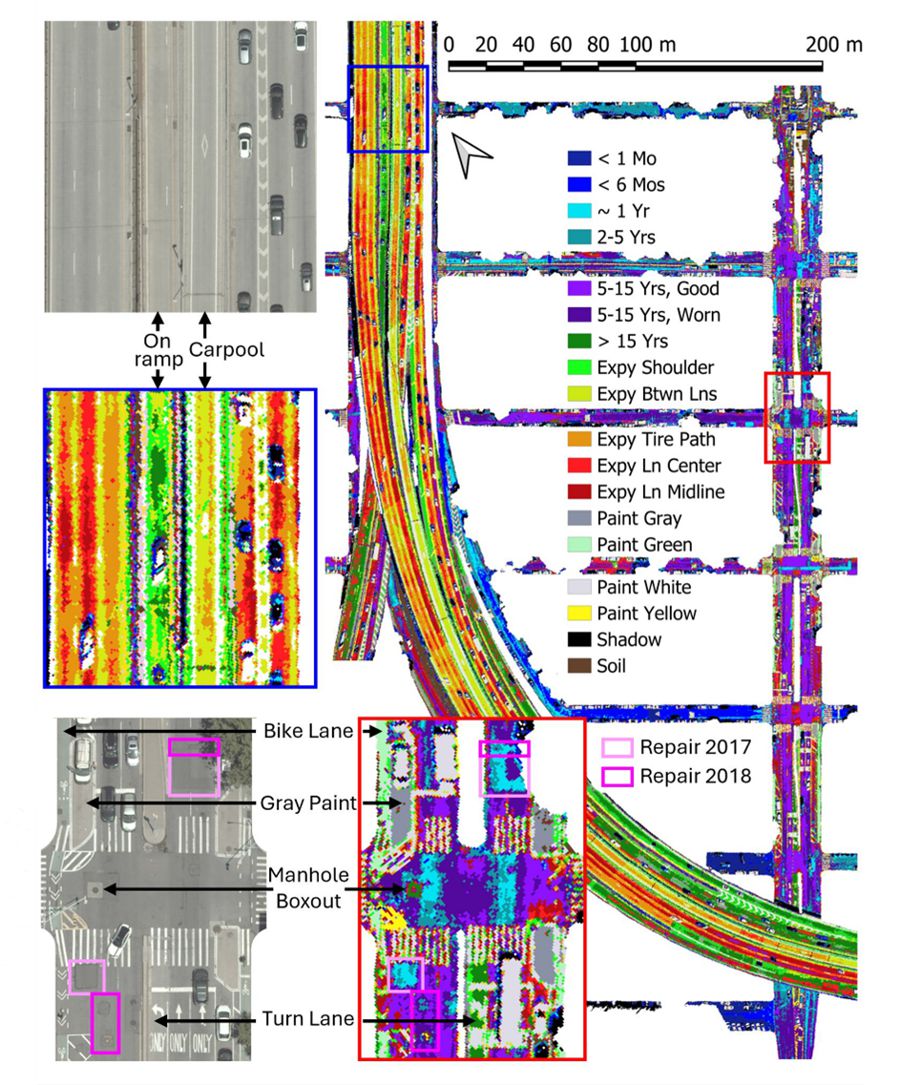

Using helicopter mounted VNIR hyperspectral data over Sunset Park in Brooklyn, the team analysed active urban roadways under real traffic conditions. The objective was ambitious: determine pavement age and repair history purely from spectral reflectance.

The results were striking.

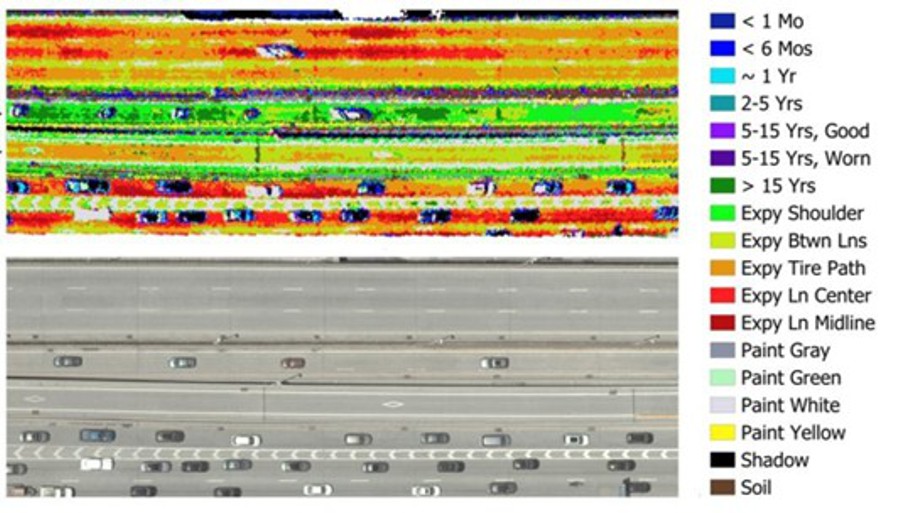

Repairs were clearly distinguishable from surrounding pavement and could be assigned consistent age estimates verified independently using satellite imagery records. Newly laid asphalt separated into three distinct classes: less than one month, less than six months and roughly one year old. Surfaces older than 15 years formed a consistent spectral group.

Even within a single lane, wear patterns varied predictably. Traffic loading produced distinct signatures across wheel paths, centre lines and shoulder areas. Heavily trafficked lanes aged differently from lighter ones, creating measurable spectral gradients.

This moves infrastructure monitoring beyond condition scoring toward lifecycle understanding. Rather than simply marking a road as fair or poor, authorities could identify when degradation accelerates and which traffic patterns drive it.

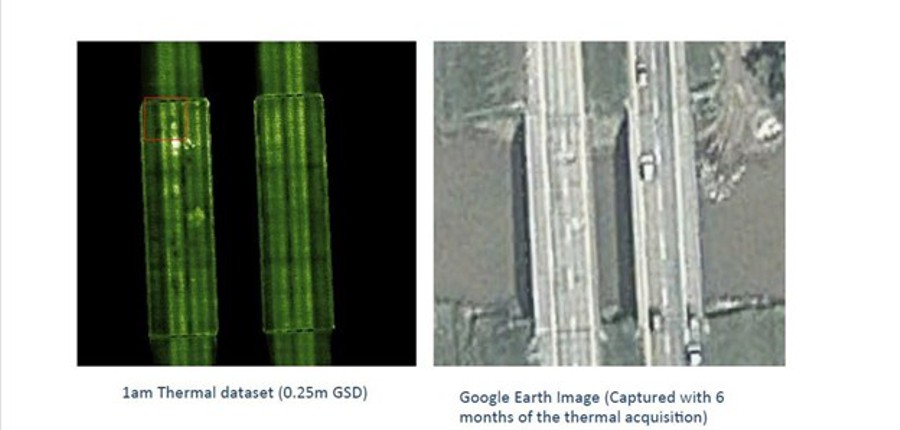

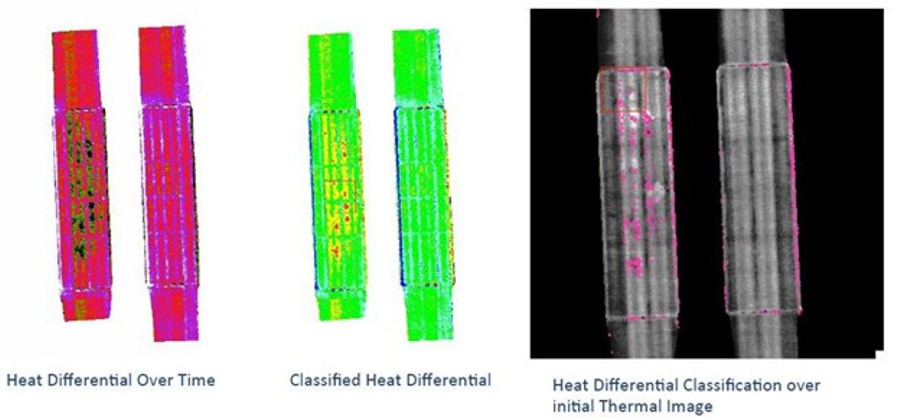

Integration With Thermal Imaging and Multimodal Sensing

Hyperspectral data does not operate in isolation. Increasingly, infrastructure monitoring combines multiple remote sensing techniques to capture complementary information.

Thermal infrared imaging, including data from sensors such as the ITRES TABI-1800, can detect subsurface anomalies in bridge decks, moisture accumulation beneath pavements and heat retention on overpasses. When paired with spectral analysis, engineers gain both material composition and structural behaviour.

For example, hyperspectral signatures may indicate oxidised asphalt while thermal imagery identifies moisture trapped below. Together they provide a fuller diagnostic picture than either technique alone. The combination helps distinguish cosmetic ageing from structural deterioration.

Globally, transport agencies are exploring similar integrations. Satellite interferometry monitors bridge movement, LiDAR measures geometry and rutting, and ground penetrating radar examines internal layers. Hyperspectral imaging adds a new dimension: chemical and material characterisation at scale.

From Reactive Maintenance to Predictive Asset Management

The implications extend beyond inspection efficiency. Maintenance planning traditionally follows a reactive model. Defects become visible, inspectors document them, and repair schedules follow available funding rather than optimal timing.

Spectral monitoring changes that sequence. Because material changes occur before visible cracking, deterioration can be identified earlier. Authorities gain time to intervene while repairs remain inexpensive.

That matters financially as well as operationally. Preventive treatments such as seal coats or thin overlays cost a fraction of full reconstruction. By detecting oxidation stages accurately, agencies can apply maintenance precisely when it delivers maximum life extension.

The approach also improves accountability. Contractors’ resurfacing work can be independently verified, ensuring treatments meet specifications and perform as expected over time. Objective measurement replaces disputes over visual judgement.

For taxpayers and road users, benefits are tangible. Better timed maintenance reduces potholes, vehicle damage and accident risk while stretching limited infrastructure budgets.

Data Driven Cities and the Future of Urban Monitoring

Cities increasingly rely on data to manage mobility networks, utilities and climate resilience strategies. Yet infrastructure condition has remained comparatively opaque. The research demonstrates that urban materials themselves can act as sensors when observed correctly.

As spectral libraries expand and metadata standards mature, authorities could monitor entire metropolitan networks repeatedly from aircraft or satellites. Change detection over months or years would highlight emerging problems long before failure.

The concept aligns with broader smart city initiatives but avoids dependence on embedded electronics or expensive instrumented pavements. Instead, the infrastructure already contains the information. The challenge lies in reading it.

For policymakers, the significance is strategic rather than technical. Massive infrastructure investment programmes require prioritisation. Objective data allows repair budgets to target the highest risk locations first, improving safety outcomes and economic efficiency.

Reading the Story Written in Light

Urban surfaces appear static, yet they constantly evolve under traffic, weather and time. Until recently, most of that evolution remained invisible. Inspection records attempted to reconstruct history after the fact.

Hyperspectral imaging reverses that relationship. The history becomes measurable directly from reflected light. Pavement age, repair chronology and wear patterns no longer rely solely on documentation. They exist physically on the surface and can be quantified remotely.

Salcido and Laefer’s work shows the built environment can be analysed with the same scientific rigour long applied to forests and geology. Roads cease to be anonymous black layers and become dynamic materials with observable lifecycles.

As cities confront mounting maintenance backlogs and tightening budgets, the ability to understand infrastructure objectively will shape investment strategies. Better information does not repair roads by itself, but it determines where each repair achieves the greatest benefit.

The emerging discipline of urban spectral monitoring therefore represents more than a technical advance. It signals a shift in how infrastructure is understood, managed and funded. The street beneath a pedestrian’s feet may look ordinary, yet in spectral space it tells a detailed story about past construction and future performance. Listening to that story could reshape maintenance planning for decades to come.