TRL looks at driver distraction and if it is time to update our evidence base

The Chief Executive of Highways England recently expressed concerns about the safety of in-car touchscreens and the potential for distracting drivers. This is a concern echoed by many fleet managers, who have seen the in-vehicle environment become ever more filled with technology designed to assist (or entertain) drivers.

TRL’s Head of Impairment Research, Dr Paul Jackson and Head of Behavioural Science, Dr Neale Kinnear, argue that the evidence base regarding distracted driving has failed to keep up with technological developments and calls for research to assess the distracting effects of the latest versions of Human Machine Interfaces (HMIs).

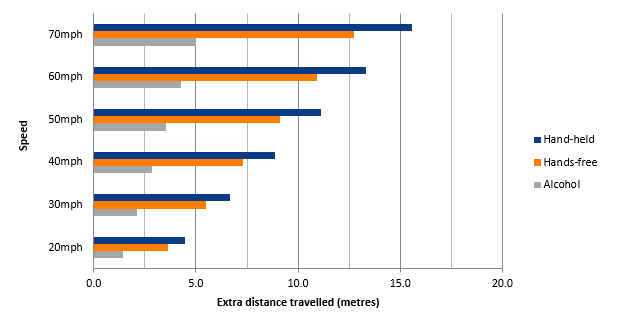

According to British law it is illegal to hold a mobile phone or satellite navigation device while driving, or riding a motorcycle. Instead, you must have hands-free access, such as a Bluetooth headset, voice command, or built-in sat nav. One of the key pieces of research evidence cited to support the law was that conducted at TRL (Burns et al., 2002), which benchmarked the distracting effects of using hands-free and hand-held mobile phones against the effects of being under the influence of alcohol.

This study showed that, compared with a control group, using a hand-held device while driving increased response times by half a second; at 70mph this would increase stopping distance by over 15 metres. Even using hands-free increased response times to such an extent that the stopping distance would be increased by over 12.5 metres when travelling at 70mph.

Subsequently, TRL’s simulated distraction drive test route has been used to investigate the level of impairment while driving caused by text messaging (Reed & Robbins, 2008) and using social networking applications (Basacik, Reed & Robbins, 2012). Kinnear and Stevens (2015) summarised the state of distraction research at the time and concluded that (p18):

‘the research suggests that the impact of distraction on safety is task dependent rather than device dependent’

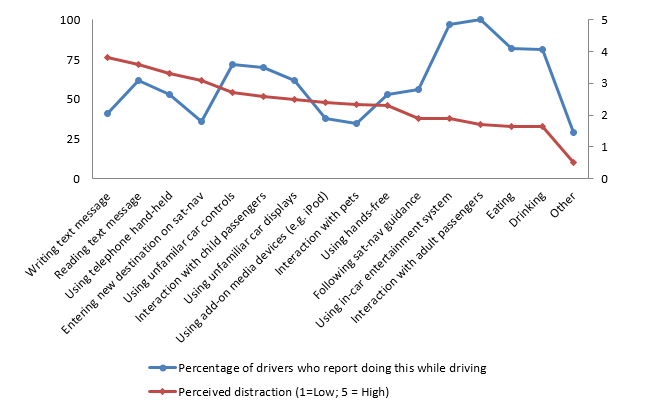

For example, text messaging is more distracting than a hands-free mobile phone call (Reed & Robbins, 2008). Similarly, Horberry et al, (2006) showed that attending to an entertainment system was more distracting than conducting a hands-free mobile phone call, while Lansdowne (2012) found that drivers perceive using unfamiliar car controls and car displays, or add-on media (e.g. music devices) to be more distracting than using a hands-free phone.

The findings from these, and similar studies, are valuable in terms of what they tell us about the distracting effects of mobile phones and earlier generations of Human Machine Interfaces (HMIs). However, in the years since these studies were conducted, the range of potential sources of in-vehicle distraction and the variety of tasks that can be conducted via HMIs has increased significantly, with a likely growth in distraction effects, as explained by Regan et al. (2014), p4:

‘The last decade has witnessed an explosion in the availability of new vehicle technology…Some technology has been built into the vehicle by manufacturers, some has been added within aftermarket products and other technologies have been brought into the vehicle by drivers (e.g. mobile phones).’

This leads to a number of questions:

- To what extent are research studies based on mobile phone use relevant to modern HMIs?

- Is further research required to investigate the effects of interacting with the latest versions of HMI?

- Should a limit be placed on the features added to HMIs, as was suggested by a panel of experts at a Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) Congress in 2016, who urged HMI designers and engineers to stop trying to turn automotive HMIs into iPhones?

TRL is involved in a range of projects at the cutting edge of developments in transport technology, such as our HELM UK, MOVE UK and DRIVEN projects. But we are also acutely aware that the one feature of the driving environment that hasn’t developed is the driver. Our advanced driving simulator enables us to test the latest in-vehicle systems in a safe, controlled environment. This enables our human factors specialists to provide guidance to regulatory authorities, OEMs and in-vehicle equipment manufacturers to ensure that the technological advances and increased levels of driver assistance offered by new HMIs do not overload the driver.

This is especially important when one considers the gradual move towards increased automation of the driving task; it will be many years before a large part of the fleet is fully, or even partially, automated – in the meantime the information presented to the vehicle operator steadily increases, while their role is gradually reduced to that of a system monitor.

Our research and understanding of this area suggests it is time that the evidence base for measuring and monitoring driver distraction should be reviewed and updated to reflect the latest developments in HMIs. Importantly, this should include an assessment of the combination effects of attending to multiple sources of information – not all of it relevant to the driving task. For example, on behalf of IAM RoadSmart, TRL is using the DigiCar simulator to measure the effects on performance of engaging with Android Auto and Apple CarPlay while driving.

Without effective regulation based on sound science, the ‘explosion of new vehicle technology’ that occurred in the last 15 years could be dwarfed by the influx of technology into the vehicle in the next 10 years. Up-to-date evidence is required to ensure that in-vehicle technological improvements don’t have unintended, negative consequences.