Claycrete II Soil Stabilizer increases stability of roads near rivers or flood Crossings

World traveler and global road builder, Brian Jackman, invented and patented Claycrete II™ over 20 years ago. The chemical soil stabilizer has the potential to stabilize pavements by reacting with the clay and then filling all the voids between the stone, grit, gravel and sand.

This inert construction material should make up roughly 90%, while the other 10% is the clay – typically identified as a problematic material, costly to haul out and useless when wet.

Brian illustrates the fact, “we are dealing with particles that are a third of the width of a human hair. So, we are not dealing with material that has good structural strength of interparticle friction.” Claycrete II™ is used to chemically alter the clay at its optimum moisture content. It then acts as a void filler, compacted and pressed between varying sizes of good quality, non plastic, material – locking in the expensive rock by pulling and creating tension, increasing stability. “Unfortunately, being able to treat clay doesn’t adjust the mechanics of proper road construction.”

The requirement for this particle size distribution is how Brian explains the extreme densities and high California Bearing Ratios, or CBRs, of pavements stabilized using Claycrete II™. “That’s the only benefit we are to road construction,” he says, “when you void fill with clay, you’re increasing the overall pavement density because you are filling the spaces that are too small to measure.”

“The potential for Claycrete II™ is not to create roads out of clay. The potential of Claycrete II™ is to take roads of really good mechanical structure and stabilize that by filling all the voids.” – Brian Jackman, patent holder Claycrete II™

“Engineers have misgivings about anyone trying to build a road out of clay, which is natural and sensible,” admits Brian. He hopes “by explaining that we’re not trying to build a road out of clay; but we’re actually using the clay to support a structure which is mechanically sound – then it makes much more sense to them.”

Claycrete II™ to Stabilize Pavements Close to Rivers and Flood Crossings

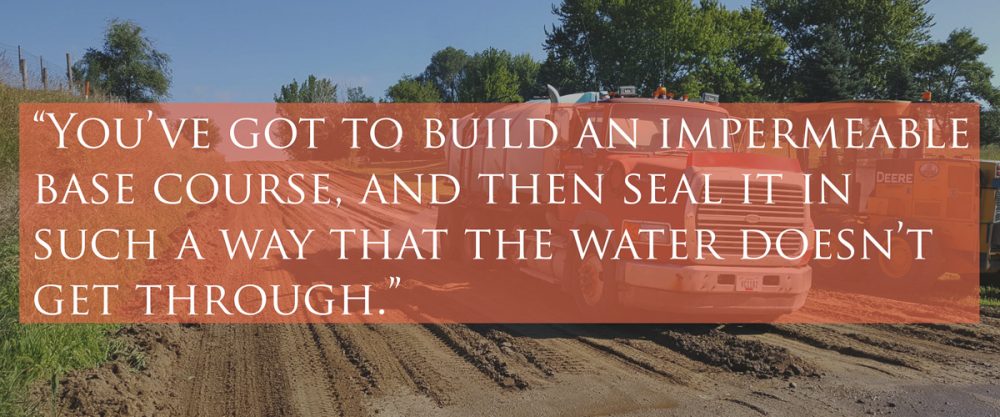

“Asphalt is a road surface, but it is not a seal” says Brian. “The reason for this,” he continues, “is because it is pervious. Water will constantly creep through it – into what is underneath.” A permeable surface is “the last thing you want if you’re going to have a freeze and thaw problem.” Instead, “you’ve got to build an impermeable base course, and then seal it in such a way that the water doesn’t get through.”

The solution recommended by sales associates at Claycrete Global will vary based on your type of road building project. Generally, Brian likes “to incorporate part of the reclaimed asphalt into the pavement design. If they’ve got the machinery and capability, they need to recover as much of the asphalt that they would want to use afterwards.” By reclaiming this asphalt “they are actually pulling part of the seal off the road, building a good road, and then putting that seal back on the road.”

Silty, wet roads are super slick if they are left unsealed. Outside of the obvious choice to build at a different site – If water cannot be avoided, then Brian and his global team have four methods to explore, as listed below:

- Elevate the Pavement

- Deep Clay Treatment

- Limestone, Clay and Asphalt Blend

- Floodways or Flood Crossings

With any technique, as stated before, inert material is absolutely required. If this is not already present, it must be imported. However; Claycrete II™ will lock this expensive material into your pavement and you should not have to rebuild the same road, or lay a ton more gravel, for quite a few years. Let’s dive into each method of building a road near a river or floodplain.

Elevate the Pavement

It can be possible to import enough inert material to lay down and build a road over it. However, latent problems, hidden during good weather, can arise when there is a freeze and thaw cycle.

Deep Clay Treatment

Say your current road is cracked, or possibly half washed away, and there is a layer of broken but good quality asphalt – varying through 60 ml to 120 ml. Then “they need to decide what they want to recover.” Brian has a simple philosophy – no waste, no harm. “If they want to recover two thirds of it, that would be good value. They can put that into a yard, recycle it and use it as a seal on top of the pavement,” but first, “they’ve got to create a base course of deep clay treatment plus imported material for a much stronger pavement.”

To create a base course in three steps, first mix the recycled asphalt and the treated clay to create a subbase down to 200 mm. Import good quality, non plastic material, that will not expand or change its shape with wet. Save money and layer the recycled asphalt and treated clay on top.

Limestone, Clay and Asphalt Blend

Once a material “has been imported and laid, and built into a pavement, you should never consider removing it or ignoring it because it is an expensive accumulation – there’s no point in ignoring the fact that it’s there, because it is an asset.”

So let’s pretend the current make-up of your road is an asphalt surface, with clay layers beneath a limestone core. In this case, Brian recommends to “mix it, rather than trying to create a limestone layer because the difference in those materials is not complementary.” He warns, “If there is a horizon between the limestone and the clay- that is where water will accumulate and lead to a failure!” However, “if they put a limestone layer and blend it in with the clay, they would have the beginnings of a suitable structural material.”

Floodways and Flood Crossings

If the road you are building crosses a flood path, the technique of constructing a flood crossing, otherwise known as a floodway, in Brian’s opinion, is “by far the best investment in road construction.” Floodways are used in Australia to build roads when its surface cannot be kept above the water. “If the base course is very dense, and water resistant, it can stand being underwater for some time – a month or two months without it soaking out.” He also notes, “floodways are a critical part of Australian road construction.”

Basically, the idea is water can run over the road when a sudden surge needs means of escape. Instead of building culverts or confining the water, “having a floodway means the water can get across at its own escape rate.” Brian’s rationale is this : when water flows across the road, “if there is more water, it will run wider and deeper and then just shrink as the water runs away – because there is no confinement, there is no damage.”

In his opinion, “culverts are restrictive and only have a certain capacity. You cannot afford to design culverts for a 1 in 500 event. Whenever you have high ground on one side and low ground on the other, even if it is 1mm, the water will run and you will have to work out the capacity for the culvert.” On the other hand, “floodways have an unlimited capacity.”

Here’s an example, “If the floodway is 2 km long and 500 ml deep, it means that once it gets over capacity the water just runs up the road on either side, or the water runs across faster for a short period of time.”

Claycrete II™ could benefit your next road construction project.