Remove toxic Forever Chemicals from groundwater with Ultrasound

New research suggests that ultrasound may have potential in treating a group of harmful chemicals known as PFAS to eliminate them from contaminated groundwater.

Invented nearly a century ago, per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, also known as “forever chemicals,” were once widely used to create products such as cookware, waterproof clothing and personal care items. Today, scientists understand that exposure to PFAS can cause a number of human health issues such as birth defects and cancer. But because the bonds inside these chemicals don’t break down easily, they’re notoriously difficult to remove from the environment.

Such difficulties have led researchers at The Ohio State University to study how ultrasonic degradation, a process that uses sound to degrade substances by cleaving apart the molecules that make them up, might work against different types and concentrations of these chemicals.

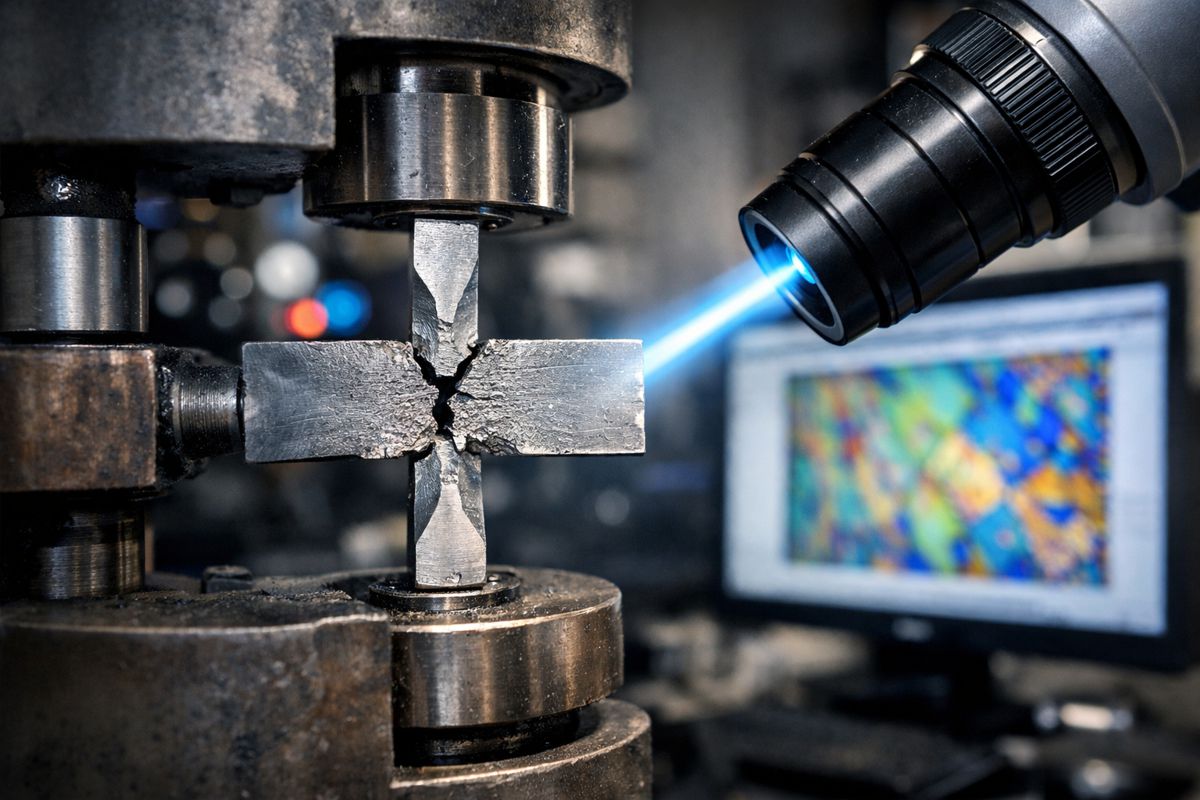

By conducting experiments on lab-made mixtures containing three differently sized compounds of fluorotelomer sulfonates – PFAS compounds typically found in firefighting foams – their results showed that over a period of three hours, the smaller compounds degraded much faster than the larger ones. This is in contrast to many other PFAS treatment methods in which smaller PFAS are actually more challenging to treat.

“We showed that the challenging smaller compounds can be treated, and more effectively than the larger compounds,” said co-author of the study Linda Weavers, a professor of civil, environmental and geodetic engineering at The Ohio State University. “That’s what makes this technology potentially really valuable.”

The research was published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry A.

One of only a few studies to probe into how ultrasound might be used to rid our surroundings of toxic PFAS chemicals, this paper is an extension of previous research of Weavers’ that determined that the same technology could also degrade pharmaceuticals in municipal tap and wastewater.

“PFAS compounds are unique because many of the destruction technologies that we use in environmental engineering for other hard-to-remove compounds don’t work for them,” Weavers said. “So we really need to be developing an array of technologies to figure out which ones might be useful in different applications.”

Unlike other traditional destruction methods that attempt to break down PFAS by reacting them with oxidizing chemicals, ultrasound works to purify these substances by emitting sound at a frequency much lower than typically used for medical imaging, said Weavers. Ultrasound’s low-pitched pressure wave compresses and pulls apart the solution, which then creates pockets of vapor called cavitation bubbles.

“As the bubbles collapse, they gain so much momentum and energy that it compresses and over-compresses, heating up the bubble,” said Weavers.

Much like powerful combustion chambers, the temperatures inside these tiny bubbles can reach up to 10,000 Kelvin, and it’s this heat that breaks down the stable carbon-fluorine bonds that PFAS are made of and renders the by-products essentially harmless. Unfortunately, this degradation method can be costly and extremely energy intensive, but with few other options, it may be something the public needs to consider investing in to protect groundwater for drinking and other uses, said Weavers.

While manufacturing industries are starting to move away from making use of PFAS, regulatory agencies are working to heighten public awareness about how to avoid them. Earlier this year, the U.S Environmental Protection Agency proposed the National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR), which would require public water systems to monitor for certain PFAS, notify the public of these levels and take measures to reduce them if they’re over a certain limit.

Because ultrasound is so effective at cleaning PFAS from solutions, the study concludes that scientists and government agencies should consider using it in future treatment technology development as well as along with other combined-treatment approaches.

Though Weavers’ research is not ready to be scaled up to aid in larger anti-contamination efforts, the study does note that their work could be the opening move toward creating small, high-energy water filtration devices for public use inside the home.

“Our research revolves around trying to think about how you scale to something bigger and what you need to make it work,” said Weavers. “These compounds are found everywhere, so as we learn more about them, understanding how they can degrade and break down is important for furthering the science.”

Other co-authors are William P. Fagan and Shannon R. Thayer, both of Ohio State.