Helion Advances Commercial Fusion With Record Temperatures

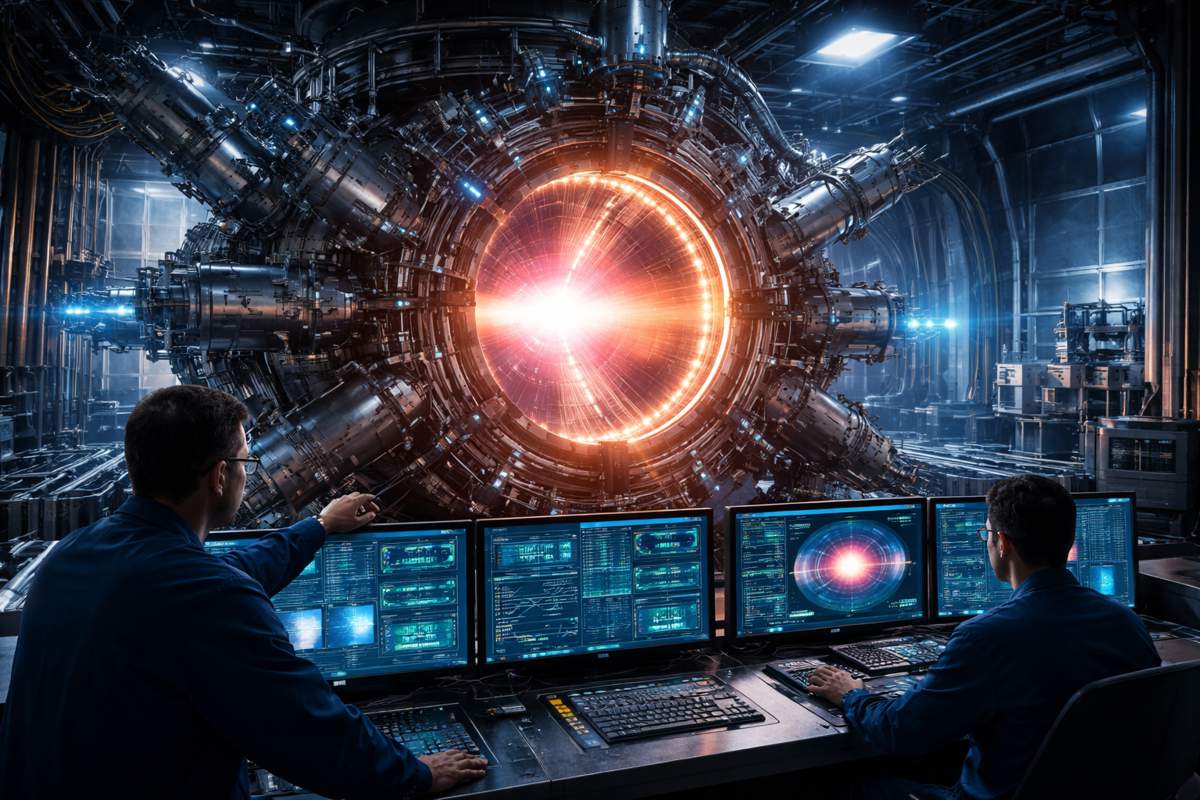

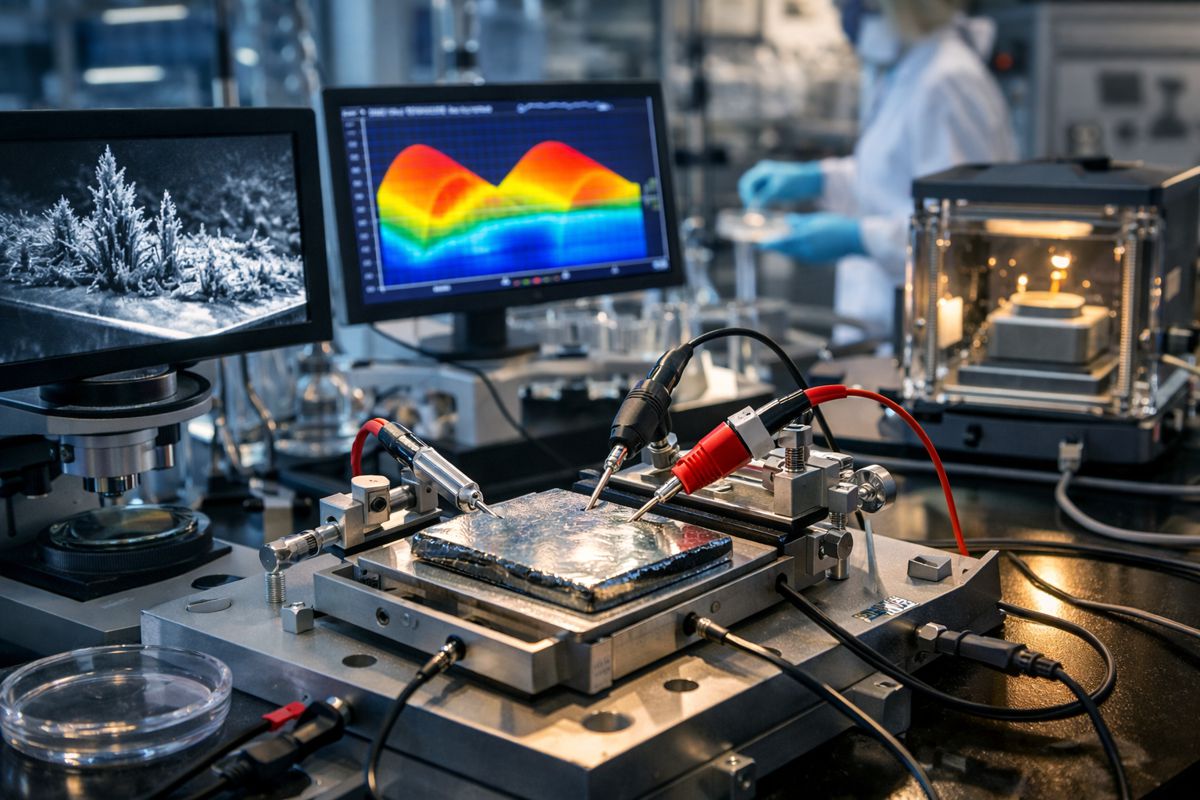

For decades, nuclear fusion has hovered just beyond reach, long hailed as the ultimate clean energy source yet persistently constrained by physics, engineering and economics. Now, the landscape is shifting. Helion, a Washington State based fusion developer, has reported that its seventh generation prototype, Polaris, has achieved measurable deuterium tritium fusion and plasma temperatures of 150 million degrees Celsius.

In practical terms, that temperature exceeds ten times the heat at the core of the Sun. In commercial terms, it signals something arguably more important: that a privately financed company is now operating in a regime historically dominated by national laboratories and multi billion pound international collaborations. For infrastructure planners and energy investors, that distinction matters. Fusion is no longer confined to publicly funded science projects. It is edging into the realm of grid supply, power purchase agreements and real world energy markets.

Why 150 Million Degrees Changes The Conversation

Within fusion science, temperature is not a headline figure for spectacle. It is a core performance metric. Around 100 million degrees Celsius is widely considered the threshold for a commercially relevant fusion plasma, particularly for deuterium tritium reactions. Helion had already crossed that benchmark with its Trenta prototype. Polaris has now pushed further, reaching 150 million degrees.

To understand why this matters, it helps to look at the Lawson criterion, the framework that defines the temperature, density and confinement time required for net energy gain. According to data from the International Atomic Energy Agency and the UK Atomic Energy Authority, deuterium tritium fuel offers the highest reaction cross section at achievable plasma temperatures, making it the most accessible pathway to early commercial fusion. Demonstrating measurable D T fusion in a private machine confirms that Polaris is operating in the relevant physics regime, not simply approaching it.

David Kirtley, co founder and Chief Executive of Helion, framed the milestone in terms of iteration and engineering discipline: “We believe the surest path to commercializing fusion is building, learning and iterating as quickly as possible,” he said. “We’ve built and operated seven prototypes, setting and exceeding more ambitious technical and engineering goals each time. The historic results from our deuterium-tritium testing campaign on Polaris validate our approach to developing high power fusion and the excellence of our engineering.”

That emphasis on rapid prototyping distinguishes Helion’s strategy from large scale tokamak programmes such as ITER, which is still under construction in France. ITER represents a multinational scientific collaboration with first plasma scheduled later this decade, but it is not designed to generate commercial electricity. Helion, by contrast, is explicitly targeting power generation and grid integration.

Tritium Approval And The Regulatory Frontier

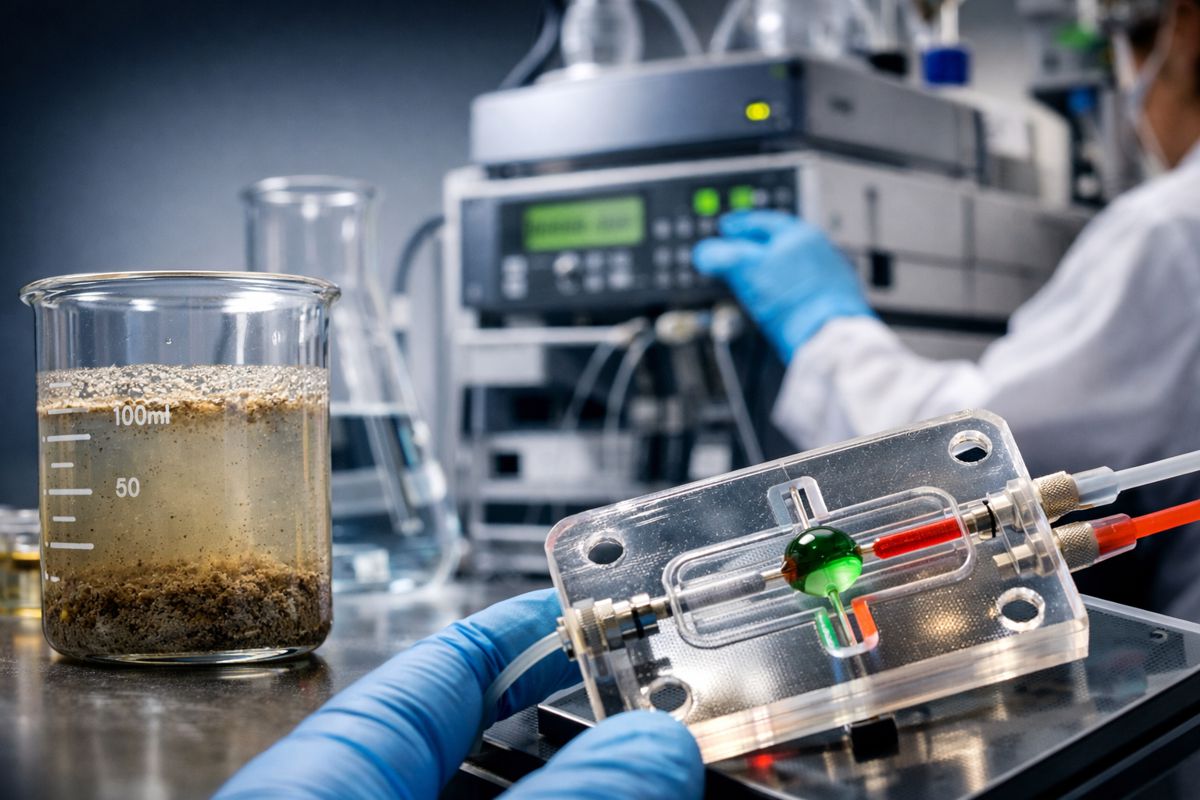

Equally significant is the regulatory milestone underpinning the technical achievement. Helion became the first private company to receive approval to possess and use tritium specifically for demonstrating fusion energy production. Tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, is tightly controlled under nuclear regulatory frameworks worldwide because of its role in both civil and defence applications.

From an infrastructure perspective, that approval is more than administrative housekeeping. It demonstrates that regulatory bodies in the United States are prepared to engage with commercial fusion developers, establishing pathways for licensing, material handling and safety oversight. For policymakers watching fusion as a potential pillar of long term decarbonisation, this is a crucial step. Without regulatory clarity, no amount of plasma performance would translate into megawatts on the grid.

Jean Paul Allain, Associate Director for Fusion Energy Sciences in the Office of Science at the U.S. Department of Energy, commented on the broader ecosystem impact: “I am impressed with our nation’s ingenuity and the pace at which we are de-risking our path to fusion commercialization,” he said. “Seeing the data from the Polaris test campaign, including record-setting temperatures and gains from the fuel mix in their system, indicates strong progress. Our ability to get fusion on the grid requires approaches that enable rapid turnaround in design and testing, and these results reflect the growing capability of the U.S. fusion ecosystem.”

The phrase “de risking” is telling. Fusion’s critics have long argued that commercial timelines slip perpetually into the future. Demonstrations of D T operation, under regulatory oversight, narrow that uncertainty gap.

From Deuterium Tritium To Helium 3 Ambitions

Although deuterium tritium is the most accessible reaction for early fusion devices, it produces high energy neutrons that activate surrounding materials. Helion’s stated commercial ambition is to operate using deuterium helium 3 fuel, a reaction pathway that yields primarily charged particles and reduces neutron related material damage.

Polaris is therefore part of a staged testing programme. The D T campaign validates high temperature operation and fusion yield. The next step is to continue increasing plasma temperatures and refine performance toward reliable deuterium helium 3 operation. Achieving that would, in theory, simplify plant maintenance, reduce shielding requirements and potentially lower lifecycle costs.

External observers have noted the technical progress. Ryan McBride, with experience spanning Sandia National Laboratories and the University of Michigan, reviewed the diagnostic data: “It is exciting to see evidence of D-T fusion and temperatures exceeding 13 keV or 150 million degrees Celsius, and I look forward to seeing more progress.”

Dr Alan Hoffman, a long standing expert in field reversed configuration plasmas, added historical context: “After reviewing the latest results from the Polaris prototype operating on D-T, I am proud of how far the field has come since the earliest FRC work at UW and Los Alamos,” he said. “I continue to see the technology scaling and Helion’s plasma energy recovery enabling this technology for commercial scale.”

Field reversed configuration research dates back decades at Los Alamos National Laboratory and the University of Washington. The difference today is scale, private capital and a direct commercial target.

Infrastructure Implications For The Energy Transition

For construction professionals and infrastructure investors, fusion can feel abstract. Yet its potential impact is tangible. According to the International Energy Agency, global electricity demand is expected to grow substantially over the coming decades, driven by electrification of transport, data centres, industrial processes and emerging economies. At the same time, decarbonisation targets are tightening.

If fusion becomes commercially viable, it could offer:

- High capacity factor power without direct carbon emissions

- Minimal land footprint compared to large scale renewables

- Reduced long term fuel supply risk

- Compatibility with existing grid infrastructure

Helion has already begun constructing Orion, its first commercial machine, in Malaga, Washington. The project is intended to deliver electricity from fusion to the grid under a power agreement with Microsoft. While timelines remain ambitious, the symbolism is clear. A private fusion company is not merely publishing plasma data. It is building plant infrastructure tied to a corporate energy off taker.

For civil engineers and EPC contractors, that translates into future demand for specialised facilities, advanced materials, radiation shielding, high power electrical systems and grid interconnections. Fusion plants, if deployed at scale, would represent a new asset class within the global energy portfolio.

Private Capital And Competitive Dynamics

The broader fusion landscape is increasingly competitive. Companies such as Commonwealth Fusion Systems and TAE Technologies are pursuing alternative confinement approaches, including high field tokamaks and beam driven systems. Venture capital, sovereign wealth funds and strategic corporate investors have poured billions into the sector over the past five years, according to industry analyses from the Fusion Industry Association.

Helion’s approach, centred on pulsed field reversed configurations and direct energy recovery, positions it within a distinct technical niche. By building and operating seven prototypes, the company argues it is compressing development cycles in a way more akin to aerospace or advanced manufacturing than traditional big science.

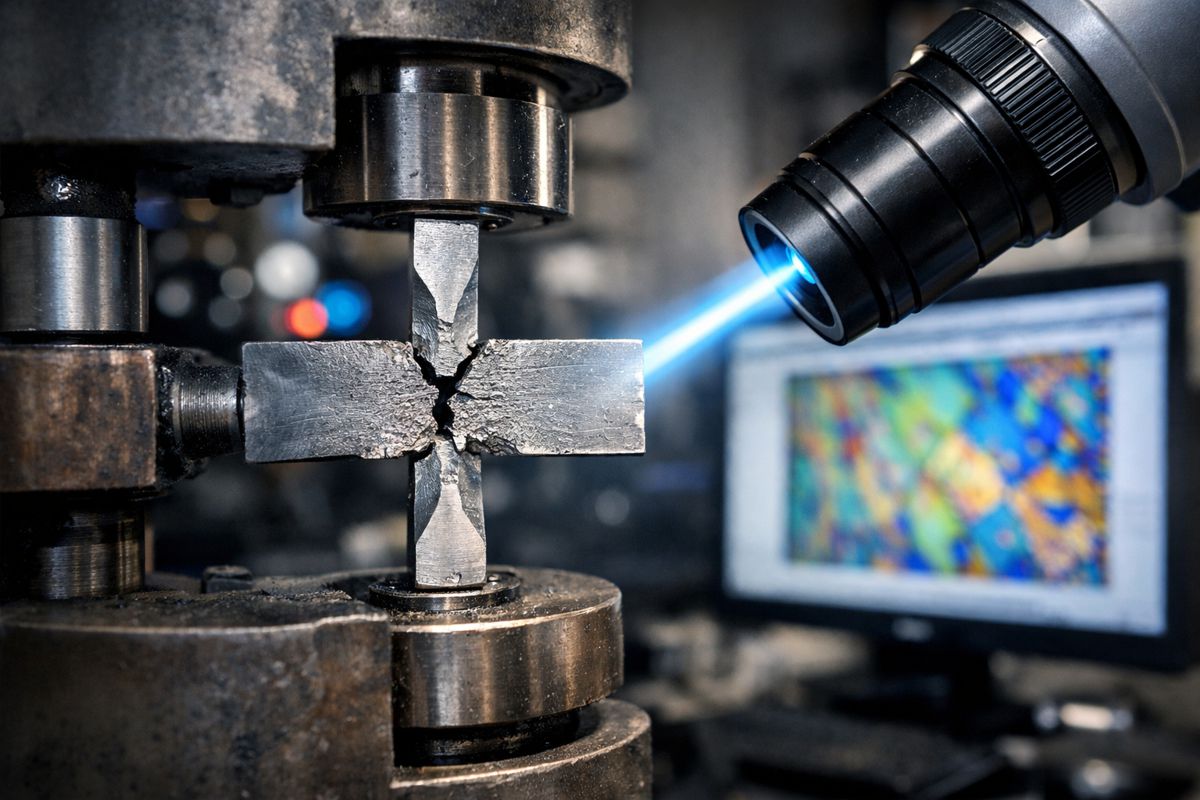

That iterative model carries both promise and risk. Rapid prototyping can accelerate learning, but scaling from laboratory pulses to sustained, grid connected operation remains a formidable engineering challenge. Materials fatigue, component lifetime, fuel cycle logistics and economic competitiveness against renewables and advanced fission reactors will ultimately determine success.

The Road From Prototype To Power Plant

Polaris does not represent commercial fusion. It represents progress toward it. The remaining hurdles are substantial. Net energy gain at system level, reliable repetition rates, cost effective tritium handling and robust supply chains for helium 3 are all critical variables.

Yet milestones matter. They shape investor confidence, regulatory engagement and public perception. Achieving measurable D T fusion and 150 million degree plasma temperatures in a private facility narrows the gap between aspiration and implementation.

For the global construction and infrastructure ecosystem, the implications are strategic rather than immediate. Fusion will not displace existing generation overnight. However, as decarbonisation deadlines approach and grid stability becomes ever more critical, diversified clean baseload options gain political and commercial appeal.

Helion’s latest results suggest that fusion is no longer simply a scientific quest. It is evolving into an industrial development programme with tangible infrastructure endpoints. If that trajectory continues, the next decade may see fusion move from laboratory curiosity to construction site reality.