Engineering Metals That Refuse to Crack

Across transport networks, power systems, aircraft fleets and industrial machinery, most structural failures do not occur in dramatic overload events. Instead, they develop quietly over time. Small repeated stresses gradually reorganise the internal structure of a material until microscopic cracks appear and eventually propagate into catastrophic fracture. Engineers call this fatigue, and it remains one of the most stubborn limitations in infrastructure reliability.

Bridges flex under traffic cycles, rail tracks experience millions of wheel passes, offshore turbines endure constant wave loading, and aircraft structures expand and contract through thermal cycles. Each event applies stresses well below the material’s ultimate strength, yet cumulative damage accumulates. According to long-established materials engineering practice, designers compensate through conservative safety factors, inspection regimes and replacement schedules. These measures work, but they add cost, weight and maintenance downtime.

In heavy transport and energy infrastructure, fatigue is particularly expensive. Wind turbine blades, jet engine components and high-speed rail axles all operate in regimes where temperature, vibration and dynamic loading combine. Increasing performance without sacrificing safety requires a deeper understanding of how damage begins at the microscopic level rather than simply increasing bulk strength.

The Atomic Scale Problem Engineers Couldn’t Predict

Traditionally, alloy development focused on maximising strength under static loading. Metallurgists refined grain structures, precipitation hardening and phase stability to prevent permanent deformation. Paradoxically, these improvements often worsen fatigue performance.

Researchers have long known why in principle but not how to control it in practice. When metals deform under repeated loading, their internal structure rearranges irreversibly through plastic deformation. Instead of spreading evenly, deformation concentrates in narrow microscopic regions. Those hotspots become the birthplace of cracks.

Project lead Jean-Charles Stinville explained the challenge: “Transportation, space and energy all create environments where there is risk for fatigue, presenting a challenge to both safety and sustainability.”

The difficulty lies in prediction. Localisation emerges from a complex interaction between chemistry, atomic ordering and mechanical stress. Even high-fidelity simulations struggle to anticipate where microscopic damage bands will form. Designers therefore relied on empirical testing rather than first-principles engineering.

A New Approach From Illinois Grainger Engineering

Researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s Grainger College of Engineering have now demonstrated a fundamentally different strategy. Instead of strengthening metals against deformation, they engineered deformation itself.

Their research shows that fatigue resistance can be dramatically improved if plastic deformation remains small and uniformly distributed across the material rather than concentrating in isolated zones. The team identified a mechanism they describe as dynamic plastic delocalisation.

Stinville clarified the idea: “In alloys, plastic deformation tends to localize into discrete regions, which ultimately become preferential sites for fatigue crack initiation.”

Rather than trying to eliminate deformation, the researchers manipulated microstructure so the material continuously redistributed strain. The result is that no single location accumulates enough damage to trigger a crack.

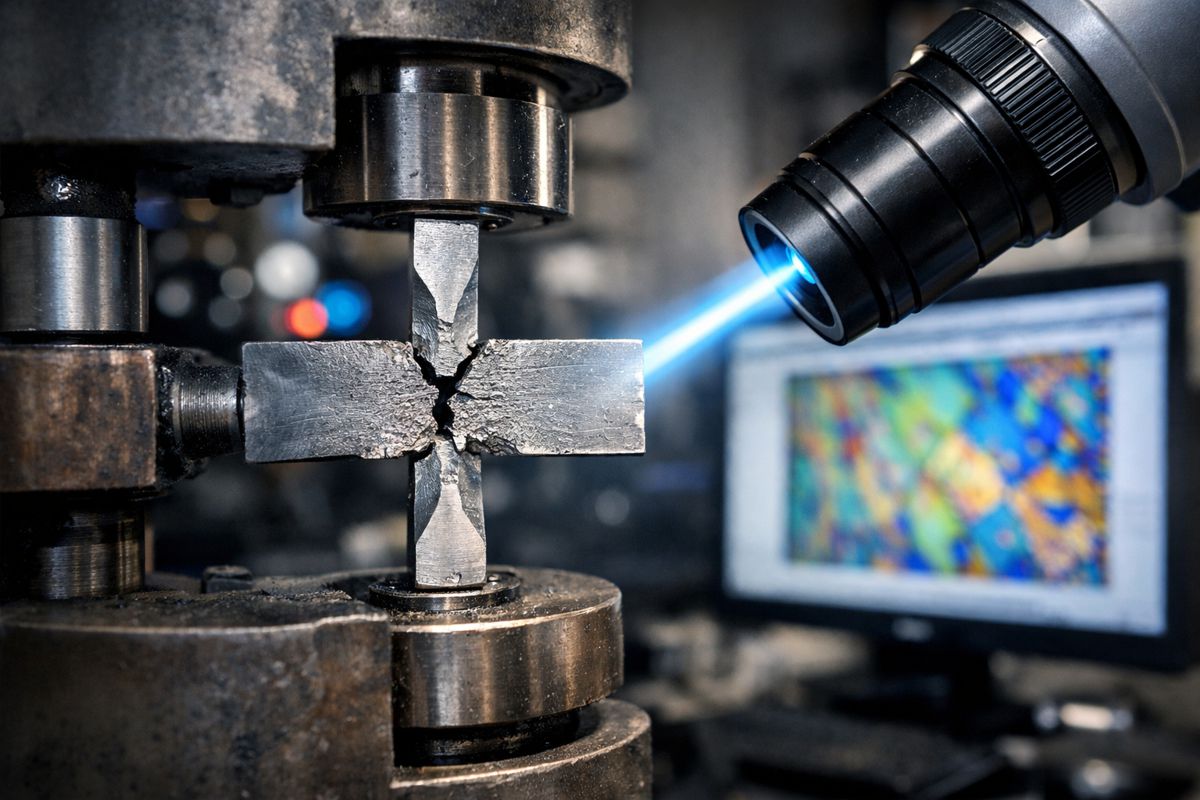

Seeing the Invisible With New Measurement Technology

Proving this concept required instrumentation beyond conventional metallurgical tools. Typical measurement techniques force a compromise between resolution and field of view. Either researchers observe tiny regions in detail or large regions vaguely. Fatigue localisation occurs across both scales simultaneously.

The Illinois team developed automated high resolution digital image correlation capable of mapping deformation over wide areas while retaining microscopic precision. This allowed researchers to watch how strain moved across the metal surface during cyclic loading.

Stinville noted the experimental challenge: “It makes sense intuitively, that spreading out the plastic deformation homogeneously makes reduces the impact of localized deformation, but experimentally demonstrating it was another matter.”

The measurements revealed a distributed deformation mode rather than the usual concentrated bands. Mechanical testing confirmed that specimens exhibiting this behaviour resisted fatigue cracking far longer than conventional alloys.

Theory Meets Computation

Observations alone could not explain why the behaviour emerged. To understand the underlying physics, the team collaborated with computational modelling experts led by Huseyin Sehitoglu. Using density functional theory and ab-initio molecular dynamics simulations, they analysed how atomic chemistry and ordering affected deformation pathways.

The models showed that particular atomic arrangements encourage cooperative motion across many lattice sites. Instead of dislocations piling up in one region, they continuously reorganise across the structure. The metal effectively dissipates damage before it can accumulate.

The combination of high-resolution experimentation and quantum-level modelling established a causal link between composition, atomic ordering and fatigue resistance. That link converts fatigue from an unpredictable phenomenon into a design parameter.

Implications for Infrastructure and Energy Systems

If the mechanism scales to industrial alloys, the consequences extend across multiple sectors. Fatigue governs maintenance cycles in infrastructure assets worth trillions globally. Increasing fatigue life by even modest margins can dramatically alter lifecycle economics.

In transport systems, longer lasting rail components reduce service disruptions. In aviation, fatigue resistant alloys enable lighter structures while maintaining safety margins, improving fuel efficiency. Energy generation may benefit even more. Wind turbines and nuclear reactors operate in environments combining cyclic stress, high temperature and radiation where material degradation drives maintenance costs.

Stinville highlighted this broader relevance: “Structural applications that involve high temperatures or radiation need materials resistant to fatigue, and our work shows how to design metal alloys that achieve this.”

The sustainability impact is equally significant. Manufacturing replacement components consumes energy and raw materials. Extending service life reduces embodied carbon, a growing priority in infrastructure policy frameworks worldwide.

Rethinking Alloy Design Philosophy

The research challenges a century of metallurgical optimisation strategies centred on strength maximisation. Instead of preventing plasticity, engineers may deliberately engineer controlled plasticity. The aim becomes damage distribution rather than damage elimination.

Historically, fatigue performance improved incrementally through empirical alloy families such as high-strength steels, nickel superalloys and aluminium-lithium systems. The new approach introduces a guiding principle that can apply across multiple material classes.

Stinville summarised the opportunity: “Now that the fundamental mechanism has been identified, we can design new alloys chemistry that activates it to produce fatigue resistant alloys.”

Rather than testing thousands of candidate alloys experimentally, researchers can target compositions predicted to maintain homogeneous deformation behaviour. This accelerates development cycles and reduces dependence on trial and error metallurgy.

What Comes Next for Industry

The immediate next step involves translating laboratory scale materials into manufacturable alloys. Industrial metallurgy introduces complications such as processing conditions, welding behaviour and long term environmental exposure. Maintaining delocalised deformation under real manufacturing constraints will determine commercial viability.

However, the concept aligns with ongoing digital materials engineering trends. Governments and industry increasingly rely on integrated computational materials engineering frameworks to shorten qualification timelines. A physics-based fatigue design rule fits naturally into these workflows.

For infrastructure owners and policymakers, the technology signals a shift from maintenance driven reliability toward intrinsic material reliability. Instead of inspecting structures more frequently, future systems may simply resist crack initiation far longer.

Toward Longer Lasting Infrastructure Systems

Fatigue has always been the silent adversary of engineering. Designers compensated through redundancy, inspection and conservative margins because they lacked predictive control at the microscopic scale. The Illinois research moves fatigue from an observational science toward a controllable one.

If further validated, the ability to engineer homogeneous deformation could redefine durability expectations in transport, aerospace and energy infrastructure. Lighter structures, reduced maintenance cycles and improved sustainability performance would follow naturally.

Rather than stronger metals, engineers may soon prioritise smarter metals, materials designed not to avoid stress but to manage it intelligently at the atomic level.