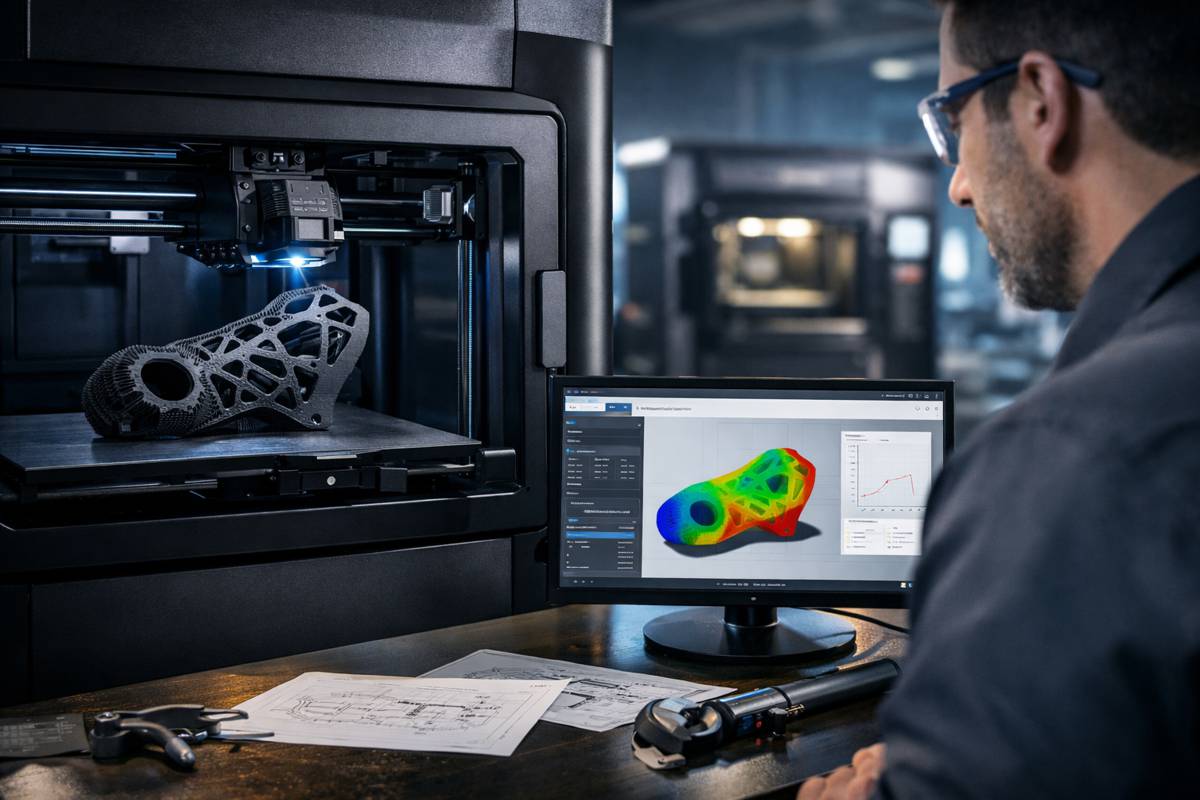

Atomic-Level Control for Metal 3D Printing for Tomorrow’s Infrastructure

Additive manufacturing has spent the last decade edging from novelty to necessity. In aerospace engineering and advanced industrial design, metal 3D printing has unlocked geometries that conventional casting and machining simply can’t deliver, from lattice-reinforced structures to complex internal cooling channels. Yet for all its promise, the technique has carried a stubborn limitation: most industrial deployments still rely on a familiar set of metallic alloys, largely because the final properties of printed parts can be difficult to predict with confidence.

That uncertainty is more than an academic headache. For construction, transport and heavy industry, unpredictability translates into risk. It complicates qualification and certification, makes repeatability harder to guarantee and raises uncomfortable questions about long-term reliability in mission-critical environments. In other words, metal 3D printing has been advancing at speed, but the materials science underpinning it has often been forced to play catch-up.

A new study led by scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), working with collaborators, suggests the gap may finally be narrowing. By focusing on compositionally complex metals known as high-entropy alloys and controlling the laser scan speed during printing, the team demonstrated a method to influence how atoms settle as metal solidifies. The implication is striking: instead of accepting the material behaviour that “falls out” of the process, engineers may be able to guide mechanical performance deliberately, down to the atomic scale.

Why Metal 3D Printing Still Struggles With Predictability

Metal additive manufacturing is not merely conventional manufacturing in a new shape. The process is defined by rapid melting and rapid solidification, often repeated layer after layer across a component’s entire build. That thermal cycling produces microstructures that are far from equilibrium, meaning the metal’s internal structure is effectively trapped in a transitional state rather than settling into its most stable configuration.

That’s exactly where the unpredictability creeps in. When microstructure changes, performance changes too: strength, ductility, fracture behaviour, fatigue life and resistance to cracking can all shift depending on subtle process parameters. In industries such as aerospace or defence, those variables are intensely scrutinised because component failure is not an option. For infrastructure projects and transport fleets, the same principle applies, simply at a different scale and operating reality: reliability must be engineered, not hoped for.

Until now, much of metal additive manufacturing has been constrained to pre-existing alloys that industry already understands, mainly because qualification pathways and property baselines exist. That makes adoption easier, but it also means the technology is, in a sense, being held back by yesterday’s materials. The LLNL work points towards a different future, one where materials are designed specifically for the unique physics of additive manufacturing rather than squeezed into it.

High-Entropy Alloys and the Search for Tailored Performance

High-entropy alloys, sometimes referred to as compositionally complex alloys, have been attracting attention in advanced manufacturing circles for good reason. Unlike conventional alloys, which typically rely on one primary element with smaller additions of others, high-entropy alloys combine several elements in significant proportions. The result is a material system with a broader design space, offering new opportunities to tune performance.

That flexibility matters for infrastructure and heavy industry because real-world demands rarely fit neatly into a single performance category. A part might need high strength, but it also needs toughness to survive impact. It might require stiffness for load bearing, but also enough ductility to resist sudden failure in harsh conditions. In transport applications, components must endure fatigue, vibration and temperature swings while maintaining predictable behaviour over long service lives.

The challenge is that the more complex the alloy, the more complex its behaviour can become during printing. High-entropy alloys are promising, but without a way to actively steer how they solidify under additive manufacturing conditions, the promise remains difficult to turn into industrial certainty. That’s where LLNL’s study draws its line in the sand.

Laser Scan Speed as a Lever for Atomic-Scale Control

The study demonstrated that adjusting the speed of the laser scan during additive manufacturing can control how atoms “lock into place” as the molten metal solidifies. Instead of treating scan speed mainly as a productivity parameter, the research frames it as a tool for material design.

The team combined thermodynamic modelling and molecular dynamics simulations to recreate the physics of 3D printing high-entropy alloys. Their aim was to understand how cooling rates shape internal structures and ultimately determine mechanical properties. The finding was that laser speed effectively governs cooling rate, and cooling rate governs the time atoms have to rearrange into stable or less stable configurations.

Deputy Group Lead Thomas Voisin described the mechanism in plain language, linking cause and effect at the heart of the approach: “By increasing the laser speed, the cooling rate increases,” explained Deputy Group Lead Thomas Voisin, “and as the material cools down faster, it has less time to rearrange to a low energy configuration. This freezes the material in a non-equilibrium state, which can be used to tune atomic structures and resulting mechanical properties.”

That idea is deceptively powerful. It suggests a shift from “print and test” cycles towards process-driven materials engineering, where the printing parameters become part of the design toolkit rather than just the manufacturing recipe.

Strength Versus Toughness Is No Longer a Fixed Trade-Off

Engineering materials has always involved balancing trade-offs. Strength and brittleness often travel together, just as ductility and softness can be linked. What the LLNL researchers found is that high-entropy alloys, when printed under carefully controlled cooling rates, can move along a spectrum of properties by changing a single process variable.

Fast cooling produces very strong material, but that strength comes with increased brittleness. Slower cooling allows more time for atoms to rearrange and settle into more balanced structures, supporting flexibility and toughness. The study frames this as tuneable behaviour rather than a fixed limitation, meaning that the same alloy system could be adjusted to meet different mission requirements.

The team’s analogy makes the outcome easy to visualise. With laser speed control, mechanical behaviour can be tuned between extremes, much like shifting from something rigid that resists force but fails suddenly, to something more forgiving that bends and absorbs energy. In practical terms, that could mean designing parts to cope with impact, vibration, repeated load cycling or sudden shock events, depending on where they sit on the strength–ductility spectrum.

For infrastructure decision-makers, this matters because it speaks directly to resilience. Bridges, tunnels, rail systems and energy networks increasingly operate under complex stress conditions: heavier freight traffic, electrification loads, climate-driven extremes and rising expectations for uptime. A manufacturing method that can deliberately tune material behaviour is not just a production advantage, it’s a strategic one.

From Trial-and-Error Printing to Programmable Metals

One of the biggest barriers to scaling metal additive manufacturing in industrial environments has been the “trial-and-error” nature of process development. Engineers adjust settings, print samples, test, refine, then repeat, often across a long learning curve. That approach can work, but it is slow, costly and difficult to generalise across different machines, operators and supply chains.

The LLNL study points towards something more repeatable: additive manufacturing as a platform where properties can be programmed rather than discovered. That’s a major conceptual upgrade. It implies that metals could be printed with microstructures designed into them from the outset, reducing uncertainty and accelerating qualification for demanding applications.

Voisin captured the turning point clearly: “We are now at a place where we can effectively design new materials that take full advantage of the additive manufacturing features like the very rapid cooling rate,” said Voisin.

That statement lands with particular weight when viewed through the lens of industrial manufacturing. Additive manufacturing has long been praised for speed, flexibility and geometry freedom. If it can now be paired with predictable, engineered properties driven by process control, it becomes a far more serious contender for scaled deployment in sectors that cannot tolerate performance surprises.

What This Means for Construction, Transport and Industrial Technology

This breakthrough sits at the intersection of materials science and industrial reality. While the study itself focuses on atomic behaviour in a specific alloy system, its broader message applies across the global construction and infrastructure ecosystem: performance can be engineered at the moment of manufacture, without relying solely on conventional metallurgical pathways.

In construction equipment manufacturing, this could open new possibilities for wear-resistant components that still resist cracking under shock loads. In rail and transport systems, it hints at parts that can be optimised for fatigue resistance and reliability under constant vibration. In energy infrastructure, it may support more advanced components where mechanical strength, temperature stability and long-term durability must align in tight tolerances.

There is also a supply chain angle. If additive manufacturing can deliver components that are both complex in design and predictable in performance, it may help reduce reliance on long, fragile manufacturing chains for specialised parts. That isn’t just convenient, it’s strategically relevant at a time when industrial supply networks are increasingly shaped by geopolitical risk, shipping disruption and national resilience planning.

The researchers also frame this as an engine for discoveries in national security and commercial industries. While the security implications are obvious, the commercial opportunity is just as significant. Industries that adopt programmable materials early could see advantages in product development speed, customisation and long-term performance reliability.

A New Direction for Manufacturing Metals at Scale

It would be premature to claim that additive manufacturing is about to replace conventional metal production across the board. Casting, forging and machining remain unmatched in many mass-production contexts. But the direction of travel is clear: additive manufacturing is evolving from a way to build complex shapes into a way to engineer materials themselves.

What makes this study notable is its simplicity at the point of control. Instead of introducing exotic new processing steps, the approach uses an adjustable parameter that already exists in the printing workflow: laser scan speed. The sophistication lies in understanding the physics well enough to treat that parameter as a tool for atomic-scale design.

As industries look toward next-generation technology, they will need next-generation materials that can be tailored not only by composition but by process. This research suggests that the future of metals may be shaped as much by thermal history and cooling dynamics as by the ingredients themselves, a subtle but profound shift.

In the wider story of industrial innovation, breakthroughs often arrive when a field stops accepting its constraints as permanent. Metal 3D printing has been revolutionary in form. Now, it may be becoming revolutionary in function too, with materials tuned by design rather than by luck, ready for the next era of aerospace, energy systems and infrastructure that simply cannot afford to fail.