NASA’s SWOT Satellite Is Redefining our Understanding of Rivers

Water doesn’t just run downhill. Over time, it redraws maps, undercuts bridges, shifts floodplains, silts up reservoirs, and quietly changes the ground rules for how infrastructure should be planned, built, and maintained. For decades, engineers and geoscientists have known this in principle, but measuring it at scale has always been the hard part. Rivers can be remote, seasonal, dangerous to survey, and maddeningly inconsistent from one reach to the next.

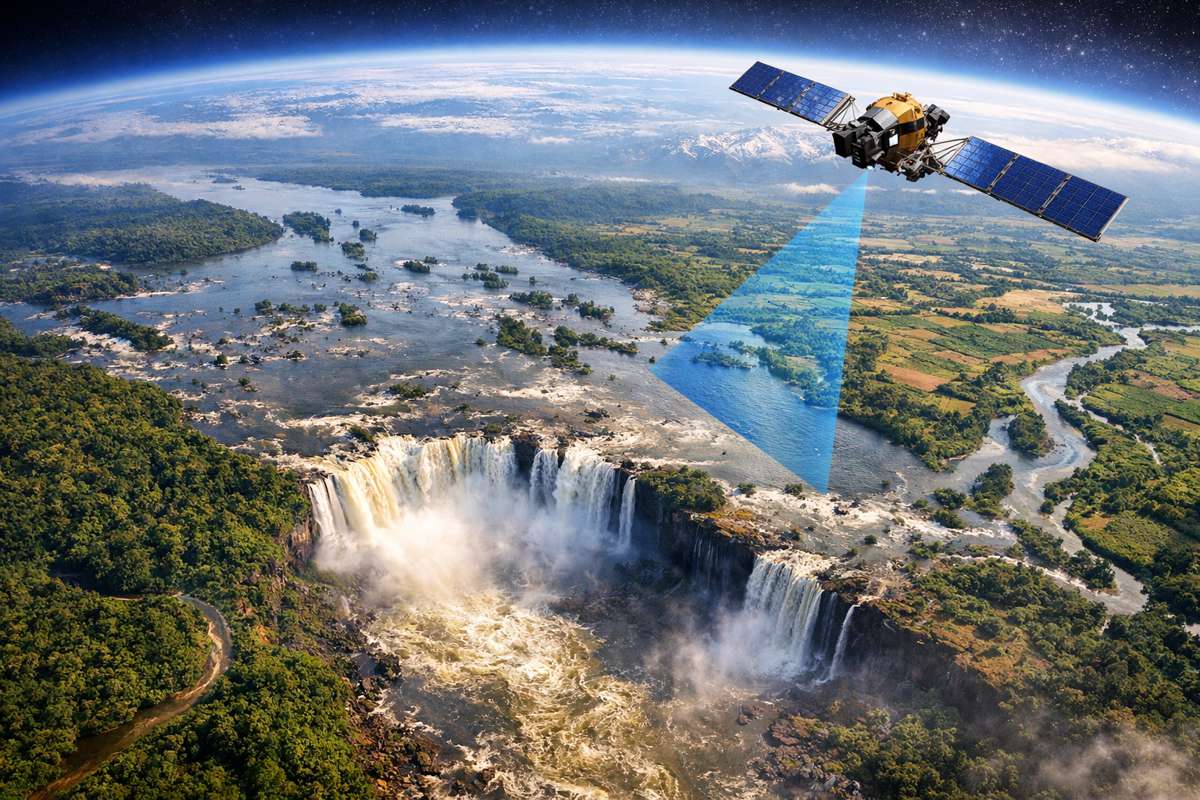

That’s why a new research effort led by Virginia Tech is turning heads well beyond the academic world. Using data from NASA’s Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite, the team has demonstrated how a mission designed to measure the height and extent of Earth’s surface water can also help answer a question with direct relevance to infrastructure owners everywhere: how exactly is water shaping the land beneath our roads, dams, and communities?

In a recent publication in Geological Society of America Today, researchers show how SWOT can be used to study the mechanics of rivers and streams at a global scale, opening the door to faster, broader insight into sediment movement, river slopes, and the physical forces that drive erosion and flooding. As climate-driven extremes become more frequent and critical assets continue to age, that kind of visibility is starting to look less like “nice-to-have” science and more like a vital early-warning system.

From Space Science to Ground-Level Consequences

NASA launched the SWOT satellite in 2022 with a clear objective: precisely measure the height and extent of bodies of water. That mission was always ambitious, aimed at improving understanding of oceans, lakes, reservoirs, rivers, and surface water dynamics worldwide.

But Virginia Tech’s contribution is, in many ways, a practical pivot. The researchers are using the same space-based measurements to explore how water physically reshapes terrain through the movement of sediment and the changing form of river channels. That shift matters because the built environment sits directly in the path of these natural processes, whether planners acknowledge it or not.

As postdoctoral associate Molly Stroud, first author of the study, explained: “We wanted to show how the satellite could be used in ways that it wasn’t primarily designed for.” She added: “How are rivers and streams moving sediment and shaping the Earth’s surface?” In the real world, the answers to those questions affect the stability of embankments, the lifespan of culverts, the risk of scour around bridge piers, and the performance of flood defences that may have been designed for a river that no longer exists in the same form.

Why River Shape and Sediment Movement Matter to Infrastructure

Rivers are not fixed infrastructure corridors. They are dynamic systems with memory. When sediment supply changes upstream, or when intense rainfall strikes a catchment, the river often responds by cutting deeper, migrating sideways, or dumping material where it doesn’t belong. That can threaten roads built along valley floors, rail lines hugging riverbanks, and communities reliant on stable channels for water supply and protection.

Sediment transport is especially important because it drives both erosion and deposition. Erosion can destabilise foundations and expose buried utilities. Deposition can reduce channel capacity, raising flood risk and forcing costly dredging or redesign. For investors and asset owners, these impacts aren’t theoretical. They turn into recurring maintenance liabilities and unexpected capital expenditure, particularly in regions where extreme rainfall is becoming more common.

Historically, understanding these river behaviours has required the kind of work that’s difficult to scale: field surveys, local monitoring stations, or airborne mapping campaigns that are expensive and limited to specific sites. That approach can deliver exceptional detail, but it rarely offers the broad coverage needed to manage risk at a regional or national level.

How Fluvial Geomorphology Gets a New View from Orbit

The scientific discipline at the centre of this work is fluvial geomorphology, which focuses on how flowing water shapes Earth’s surface. It is a field with enormous relevance to the transport and infrastructure sector, even if it sits outside most day-to-day engineering conversations.

Virginia Tech’s research highlights an emerging shift: instead of studying one river reach at a time, SWOT makes it possible to see patterns across entire river networks. That scale changes what can be asked, and what can be answered.

George Allen, associate professor in geosciences, believes this capability has not been fully recognised in the wider fluvial community. As he put it: “I don’t think it was any secret that SWOT could probably be used for fluvial geomorphology, but the great potential of the satellite wasn’t on the radar for much of that community.” He continued: “The purpose of this paper was to say, hey, look, there’s this great new tool that can be used to do brand new things in this field.”

For infrastructure planners, the implication is straightforward. If river behaviour can be monitored systematically and frequently, agencies can begin to shift from reactive repairs to proactive risk management, based on measurable physical change rather than assumptions.

What SWOT Changes for Fieldwork, Surveys, and Decision-Making

Until now, much of river science has relied on detailed but fragmented datasets. Researchers and consultants have typically used airborne surveys or intensive fieldwork, often focusing on one reach, one catchment, or one critical site. That makes sense when budgets are constrained, but it also means risk is often evaluated in isolation, without understanding what is happening upstream or across neighbouring systems.

Traditional approaches involve mapping river cross-sections and using them to estimate key variables such as sediment carrying capacity and flood likelihood under different conditions. These methods can be robust, but they are slow, labour-intensive, and difficult to repeat frequently enough to capture change between extreme events.

SWOT changes that equation by offering a consistent, repeatable way of observing river surface characteristics over huge areas. Stroud described the potential scale shift clearly: “SWOT allows us to cover all the rivers in the world and understand how they’re evolving.” She added: “It really transforms the scale at which we can study rivers.” Even if engineering teams continue to rely on field survey for design-grade detail, satellite-derived insight can help identify where to focus resources and when conditions may be changing faster than expected.

Three River Applications With Big Industry Implications

To demonstrate SWOT’s capabilities for river science, the Virginia Tech team focused on three practical applications. Each one intersects with real challenges faced by infrastructure operators, environmental agencies, and project financiers.

The first application involves large river dynamics. Large rivers act as economic arteries, supporting navigation, water supply, hydropower generation, and settlement patterns. When they change course or depth profile, consequences can ripple across multiple sectors, from port operations to flood protection. Having a tool that can observe large-scale river behaviour consistently helps agencies understand evolving risk along entire corridors, not just at a few monitoring stations.

The second application focuses on sharp breaks and slopes along rivers, including waterfalls or sudden drops. These features may be dramatic to look at, but they are also indicators of energetic systems capable of rapid erosion. In infrastructure terms, steep river sections can be hotspots for scour, slope instability, and sediment pulses that affect downstream bridges and floodplains. Monitoring how these breaks evolve over time could improve understanding of where erosion is accelerating and where intervention might be justified.

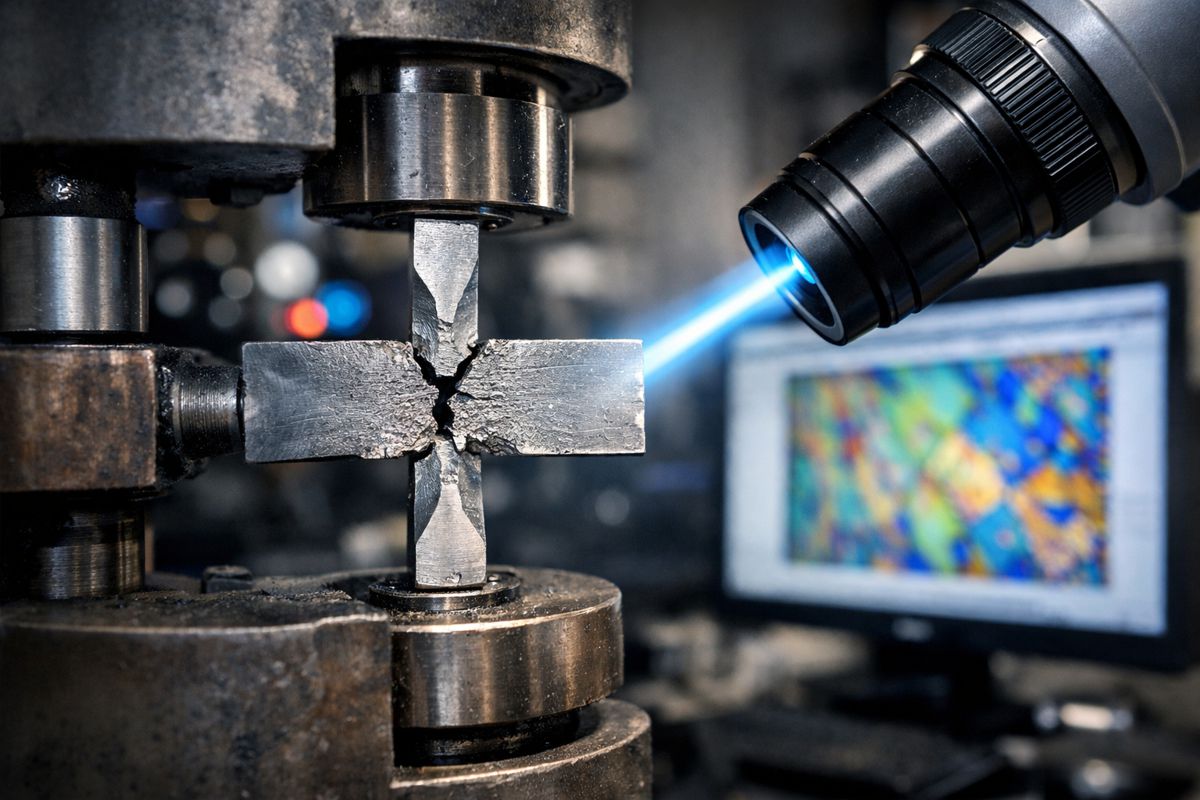

The third application examines shear stress, a key variable that helps determine how much sediment water pushes along. Shear stress is deeply tied to the ability of a river to erode its bed and banks or to transport sediment downstream. If shear stress increases due to higher flows or altered channel geometry, the risk of erosion rises. If it drops, sediment may settle out, reducing capacity and potentially increasing flood risk. Either way, it’s the sort of insight that can help bridge engineers, flood managers, and asset owners understand not just where water is moving, but what it is doing.

Dam Failures, Aging Infrastructure, and a Growing Monitoring Gap

Beyond natural river processes, the study also explored how SWOT could be used to observe and track dam failures. That matters because dam infrastructure across many countries is aging, and failure risk can increase under more frequent and intense flooding.

The team, which included Julia Cisneros of the Department of Geosciences alongside collaborators at the University of Colorado and Brown University, investigated how satellite monitoring might contribute to understanding dam failure events and their effects on river systems. Their interest is grounded in a sobering reality: there are thousands of dams across the United States alone, and it is often difficult to predict exactly when a dam might fail or what long-term effects such a failure could trigger.

The immediate impacts of dam failure are obvious: sudden downstream flooding, damage to roads and structures, and hazards to communities. But the longer-term consequences can be just as significant, including rapid channel incision, redistribution of sediment, and ecological shifts that can affect land use and water systems for years.

As Stroud noted: “As SWOT accumulates a longer record, we’ll be able to get a better understanding of questions like these and others in the field of fluvial geomorphology.” That “longer record” is crucial. Many infrastructure risks emerge slowly through cumulative change, only becoming obvious when a threshold is crossed. Satellite observation may help spot those trends earlier, giving asset managers time to act.

What This Means for Construction, Transport Networks, and Investors

For construction professionals, the immediate takeaway is that river and flood risk intelligence may be about to get cheaper, broader, and more accessible. That could reshape how projects are scoped in early planning stages, particularly for roads, bridges, and energy infrastructure built near rivers.

If SWOT-derived analysis can help identify reaches with unstable slopes, elevated shear stress, or changing dynamics, then feasibility studies can become more targeted. Instead of treating river risk as a generic box-ticking exercise, developers can prioritise where deep geotechnical investigation is actually needed and where mitigation will likely pay off.

For investors and policymakers, this research also supports a wider shift towards resilience as a measurable, monitorable characteristic of infrastructure. When climate variability increases uncertainty, the value of consistent datasets rises. Tools like SWOT won’t eliminate uncertainty, but they can improve the visibility of physical change, turning unknown risk into quantifiable risk.

In the long run, there’s a compelling argument for integrating satellite-derived river monitoring into broader asset management systems. Infrastructure is already shifting towards digital twins, predictive maintenance, and data-led intervention. Understanding how the landscape itself is evolving, particularly around water, is a missing layer that could help align design, operations, and long-term investment planning.

A New Era of Global River Insight Begins

The Virginia Tech team’s demonstration of SWOT’s versatility is more than a clever repurposing of a space mission. It’s a reminder that some of the biggest gains in infrastructure resilience come from seeing familiar problems in a new way.

By expanding the scale of fluvial geomorphology, SWOT may help researchers and practitioners understand rivers not as isolated systems but as globally connected patterns of movement, energy, and change. That’s valuable for science, certainly, but it is also valuable for the people making high-stakes decisions about where to build, what to protect, and how to manage infrastructure that must endure in a more volatile climate.

And perhaps most importantly, it offers a shift in mindset. Rivers don’t fail infrastructure overnight. They reshape the world slowly, stubbornly, and relentlessly. Having a tool that can watch that story unfold, globally and consistently, could become one of the quiet revolutions behind safer bridges, smarter planning, and more resilient communities.