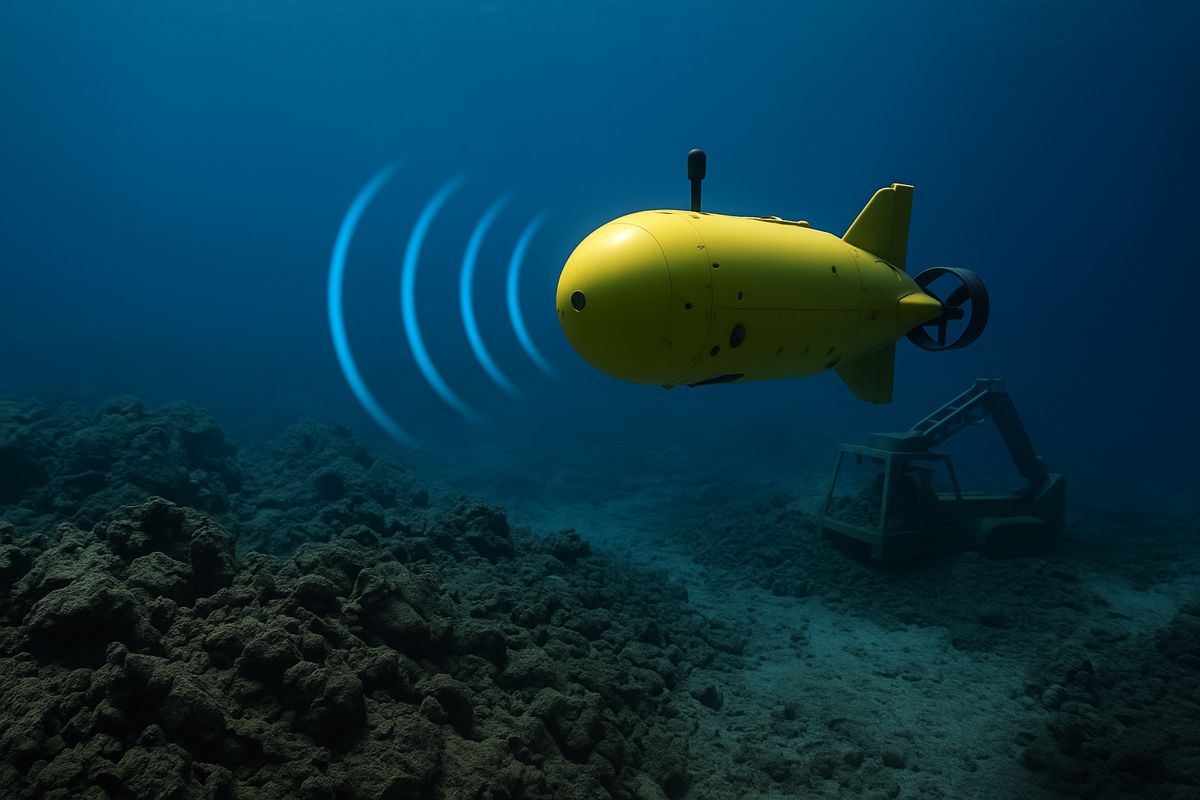

Acoustic Innovation Connecting Drones and Underwater Robots

Sound behaves unpredictably when it encounters different mediums, and nowhere is this more apparent than at the interface where air meets water. Anyone attempting to shout underwater quickly learns that the message rarely reaches listeners above the surface.

The contrasting densities of air and water create a high level of acoustic impedance, preventing most vibrations from crossing the boundary. Instead of passing through, sound waves tend to reflect back, making effective communication between underwater and airborne environments extremely challenging.

Researchers have long explored ways to bridge this natural acoustic barrier, especially as the fields of ocean robotics, underwater navigation and maritime communications continue to evolve. A new development from Rutgers University may offer a promising breakthrough. Doctoral student Hesam Bakhtiary Yekta has designed and simulated a metamaterial specifically engineered to enhance sound transmission between air and water.

Bakhtiary Yekta presented his findings during the Sixth Joint Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the Acoustical Society of Japan, held in Honolulu, Hawaii. His work demonstrates the potential to transform communication between autonomous surface drones and underwater robotics, enabling more cohesive operations across a broad range of marine applications.

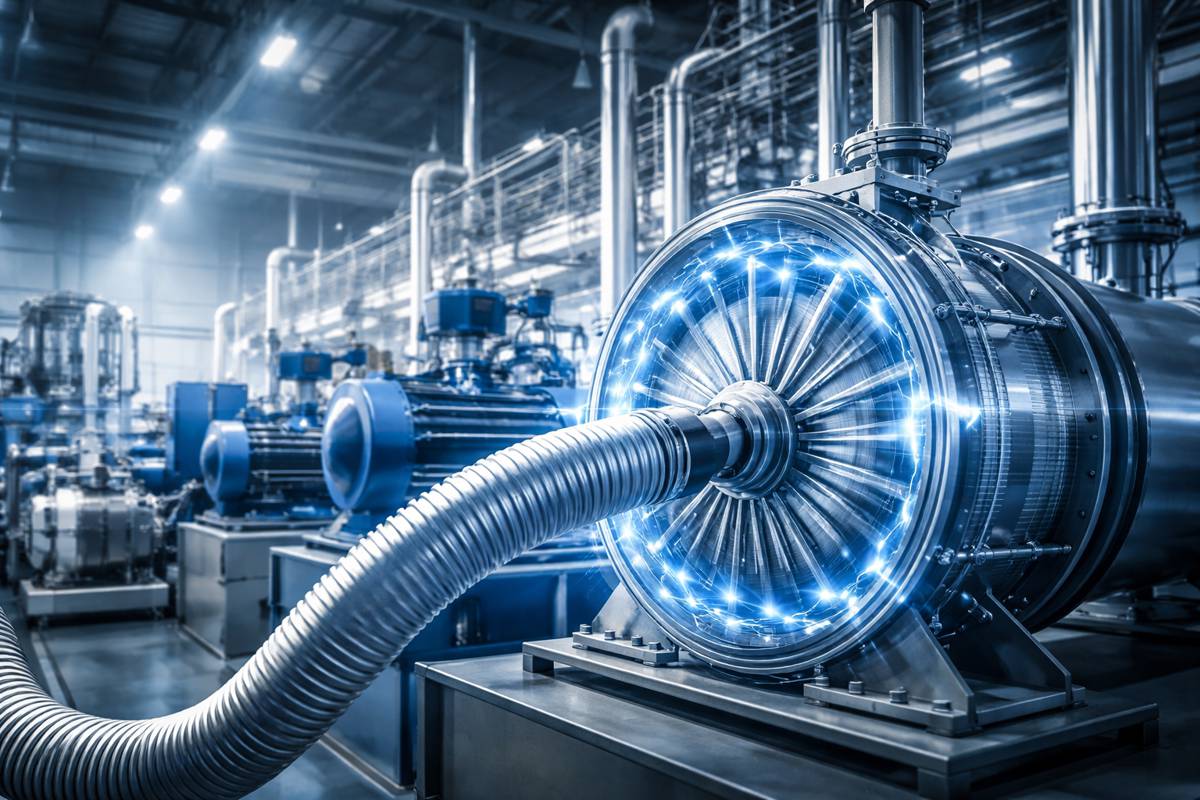

Designing a Simple and Efficient Metamaterial

The metamaterial created by Bakhtiary Yekta consists of a layered structure featuring three aluminium plates separated by steel ribs. Positioned at the exact boundary between air and water, this material transfers acoustic energy through its physical geometry, reducing reflection and allowing sound waves to move more efficiently across the interface.

He explained the advantages clearly: “One of the reasons our design stands out from others is its simplicity”. According to Bakhtiary Yekta, the aluminium plates are easy to obtain and widely used in industry, while the steel ribs reinforce the structure and control both its resonant and acoustic behaviour. This simplicity not only makes experimental testing more feasible, but it also improves scalability for commercial or field deployment.

The metamaterial operates passively, requiring no power supply or advanced electronics to function. Its behaviour relies entirely on geometry and resonance, a compelling feature for systems that demand reliability in harsh marine environments.

Enhancing Communication Between Land, Sea and Sky

The potential uses extend well beyond laboratory study. Bakhtiary Yekta envisions this metamaterial as a tool for two-way communication between underwater devices and aerial systems such as drones. Autonomous vehicles operating underwater often rely on acoustic signalling, while airborne robots depend on radio communication or line‑of‑sight signals. These approaches rarely interact smoothly.

He elaborated on this capability: “The robot could send an acoustic signal at a specific frequency toward the structure, which is designed to resonate at that frequency and allow the sound to pass from water into air”. By carefully tuning the metamaterial to particular frequencies, the structure could transmit messages across mediums using a completely passive mechanism with sufficient bandwidth for real‑world communications.

This approach could simplify underwater operations dramatically. For example, offshore monitoring drones could receive updates from subsea robots without complex tethered links or expensive relay networks. The result would be more efficient marine surveying, safer inspection of underwater pipelines or assets and more coordinated response during maritime emergencies.

A Step Toward Practical Deployment

Bakhtiary Yekta has already filed a provisional patent for the design, indicating strong confidence in its potential for practical application. His next steps include expanding the patent work and pursuing experimental testing to confirm the theoretical and simulation‑based results.

He noted: “My next goal is to continue developing the patent and explore the possibility of running an experiment to verify our simulation and theoretical results”. Experimental validation will be crucial to demonstrating performance in varied ocean conditions, where salinity, pressure and turbulence may influence acoustic transmission.

If the material behaves as predicted, it could advance communications for multiple industries:

- Offshore energy infrastructure

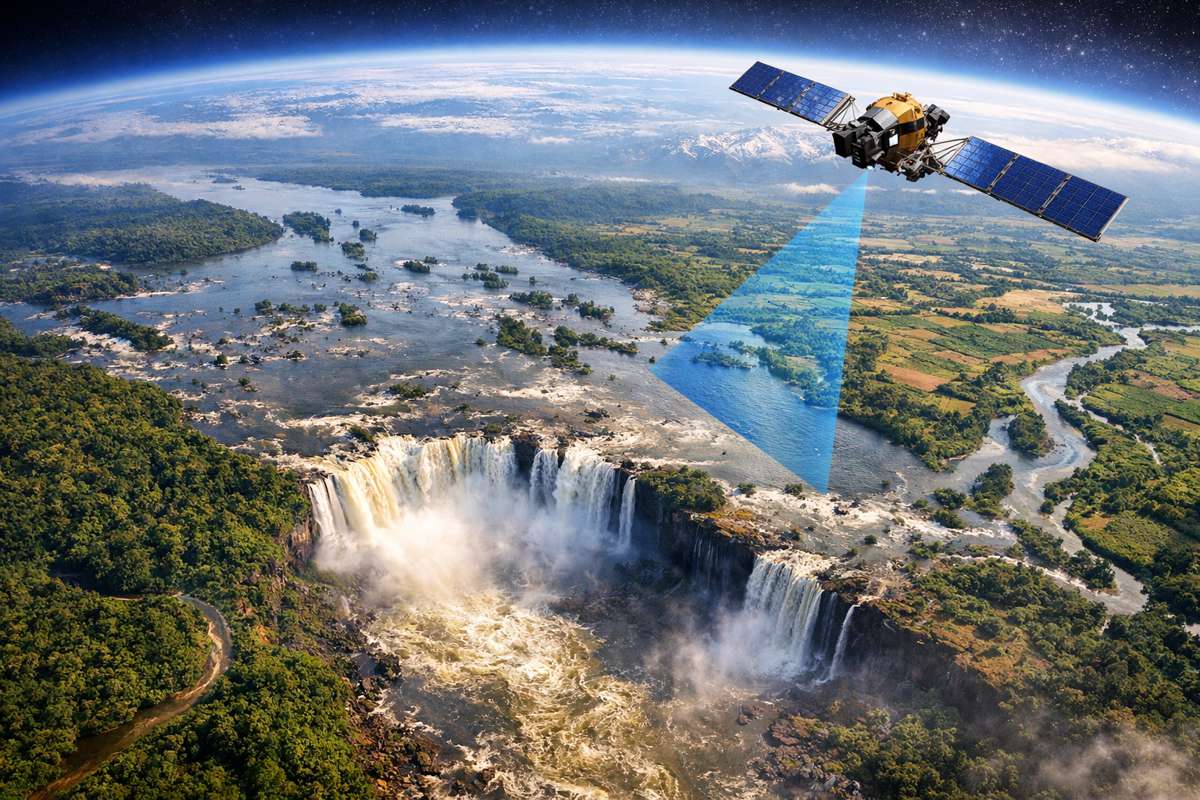

- Environmental monitoring and marine science

- Naval technology and underwater surveillance

- Remote inspection of subsea installations

- Smart maritime logistics and port automation

Each of these sectors increasingly relies on remote vehicles and intelligent sensing systems. A passive structure capable of bridging two communication domains could simplify system architecture, reduce operational cost and improve safety.

Scientific and Industrial Potential

The study of metamaterials has accelerated over the last decade, especially for electromagnetic and acoustic applications. Acoustic metamaterials are engineered to manipulate sound waves by shaping resonance and mechanical vibration. Many have been designed for noise damping, vibration control or sound focusing.

At the air‑water interface, this new metamaterial suggests a unique function: enabling energy transfer without electronics, membranes or power input. This could influence how underwater drones, subsea inspection robots and autonomous ships coordinate tasks. Marine industries are increasingly turning to digital twins, real‑time robotics and AI‑assisted monitoring. Seamless communication remains one of the biggest operational hurdles.

The design stands apart because it prioritises manufacturability and resilience. Without delicate membranes, electronics or polymers, aluminium and steel are well‑suited to marine deployment. Both materials tolerate corrosion when properly treated and offer high mechanical strength in shifting currents.

More advanced metamaterial variants may follow. The structure could be adapted for different resonant frequencies or optimised geometries for specific immersion depths or environmental conditions. This adaptability could extend its usefulness in defence, offshore wind inspection, aquaculture and even research involving marine mammals that rely heavily on sound.

A New Frontier for Marine Technology

As global industries invest in ocean exploration and sustainable offshore development, technologies that remove communication barriers are gaining traction. Maritime safety systems, inspection robotics and smart environmental monitoring already require cross‑realm coordination. Systems often rely on multi‑layered relay nodes or expensive acoustic modems to communicate effectively.

A passive structure such as Bakhtiary Yekta’s metamaterial could streamline operations considerably by reducing the number of required interfaces. This would be especially valuable for unmanned missions far from stabilised infrastructure, including deep‑sea operations, emergency response scenarios or offshore asset inspections.

Further research will explore whether the material can handle broadband acoustic frequencies or if multiple units tuned to different ranges will be needed for more advanced applications. Laboratory testing will likely examine environmental sensitivity, corrosion resistance, long‑term durability and pressure performance.

Remote Maritime Communication

The metamaterial designed by Bakhtiary Yekta opens a fresh perspective on underwater acoustic engineering. With continued development, practical testing and refinement, it may become a cornerstone of remote maritime communication. Maritime robotics is rapidly advancing, and solutions enabling seamless cross‑medium communication could accelerate innovation.

If validated through field testing, this technology could simplify offshore automation, enable real‑time coordination between underwater drones and surface vehicles and reduce reliance on costly communication infrastructure. As industries push deeper into ocean environments, innovations such as this will help bridge the gap between research, technology and commercial deployment.